Early Meiji Japan and Public History: Ports, Public Memory, Gateways to Understanding through Photography

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

Abstract

The success of the Meiji regime elite in placing Japan on the road to unprecedented rapid economic development is for all to see in the public history displayed within the port districts of Yokohama, Kobe and Nagasaki. Silence marks the history of how important these port-rail-communications developments were to the restoration of Japan’s own sovereignty and the simultaneous stripping away of others. This work explores the state and left-unstated reasoning behind Meiji Japan’s elevation to become the first non-western power utilising the authors photography of the public history of Japanese ports and their indispensable rail and communications connections.1

*

It has been observed that technological change is a political process, and while this certainly is often the case, in Meiji Japan, the inverse could be argued: political change was a technological process (Free, 2008: 40).

Introduction

Contemporary visitors, domestic and foreign, to Japanese ports such as Yokohama, Kobe, Nagasaki and others are able to spend several days exploring the public history of these gateways between Japan and the world. The focus of the public history, of these cities, centres primarily on their emergence during the Meiji period (1868-1912) of Japanese history. The story of Meiji Japan’s rise to modern governance and the establishment of the foundations for a modern national and global economy has been thoroughly explored by others and will not be retold in full here. As works by Najita (1974, 1993), Giffard (1994), Fallows (1995), Morris-Suzuki (1994), Samuels (1994), Beasley (1995), Sims (2001), Andressen (2002), Miyoshi (2005), Schuman (2009), Studwell (2013), Tang (2011, 2014), Kasza (2018) and others highlight, this technological revolution on Japanese soil required the upheaval of almost every aspect of society. Free (2008: 15) in his seminal study on Japanese railroad development states:

Henceforth, the transfer of western technology to Japan would become a notable aspect of Japan’s interaction with western civilization: small initially, but accelerating at an amazing pace during the Meiji period.

The accumulative effect of which would be to transform Japan under Emperor Mutsuhito’s reign (1868-1912). This work will examine, through both writing and a selection of photographs taken by the authors, the economic and international trade history of Meiji Japan as exercised in the port cities of Yokohama, Kobe and Nagasaki and now only partially reflected through public history.

This paper will show how this public history opens avenues for the exploration of in what ways the historic ports of Yokohama, Kobe and Nagasaki offer a means of understanding how the Meiji men of Japan learnt about the world they wished to catch up with, and, simultaneously drove seismic changes within Japan. More specifically, Japan’s advancements included: political, governance, agricultural reforms, infrastructure development; and the establishment of banking facilities to accommodate greater foreign trade, policy reforms in adherence with adoption of the global default ‘gold standard’, and the introduction of foreign human capital and others public policy initiatives (Hoshi & Kashyap, 2001; Plung, 2021). Ultimately, however, the ports and their development (including that of their essential partners in the form of rail and the telegraph), highlights the central driving force behind the Meiji Restoration: the elevation of Japan to full sovereign, strategic, economic and social equality with the very same international powers (Great Britain, continental European and the United States of America) that had denied Japan such status through the unequal treaty system imposed upon the nation from the 1850s onwards (Najita, 1974; Sukehiro, 1988; Auslin, 2004; Holcombe, 2011; Iokibe and Minohara, 2017).

The most significant expression of this national transformation through adoption, adaptation and development of a modern industrial nation’s systems took place in the form of an unprecedented (in both scale and scope) mission abroad, the Iwakura Embassy which took place from late-1871 to 1873 (Kume, 1871-1873; Miyoshi, 2005; Caprio, 2020). The Embassy fulfilled the fifth element of The Charter Oath (Gokajo no Goseimon) with outlined the core objectives of the Restoration of the Emperor: 5. Knowledge shall be sought throughout the world so as to invigorate the foundation of Imperial rule (Hane Mikiso as cited in Sims, 2001: 11). The Embassy, as with either a single individual Japanese person or a large collective of the ruling elite, then had one specific purpose: to accumulate knowledge that would strengthen the emperor’s rule not only domestically, but within any other territory acquired under his banner. Knowledge acquisition was to be on empirical studies with a high level of transferability that built the Japanese state that operated under the emperor. For any other purpose, personal aesthetics, pleasure or other, knowledge acquisition was for-all-intent-and-purposes a treasonable act. One of the two chroniclers of the Embassy, Kunitake Kume (1871-1873, Vol 1: 4) would come to recognize that the Embassy was both the product of and captured forces changing not only Japan’s trajectory, but the concert of nations:

When we consider what has happened, we realize that everything was related to changes in the trend of world affairs.

Whatever knowledge was beyond the shores of Japan that could position the emperor to consolidate his domestic rule and elevate him and his nation to new predominance amongst the league of nations, it was the duty of those sent abroad in whatever capacity to acquire it.

The Embassy would see current and future Meiji leaders travel across the United States of America, Great Britain and continental Europe. Initially, the mission held the aim of revisions to the unequal treaty system, and, to empirically examine and document the political, policy and developmental processes taking place in the advanced nations that would enable Japan to begin its ascendancy (Chang, 2002). However, the Iwakura men would come to conclude during their early-1872 time in Washington D.C. through extensive diplomatic dialogues (with U.S. Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, European diplomatic figures present in the national capital, and through communications with Meiji diplomats in London), that that unequal treaty revisions at this time were undesirable. Instead, the travellers moved concertedly and energetically to focus the purpose of the Embassy to extensively documenting the politics, governance, agrarian, financial, industrial, educational and socio-civic advantages that the western powers held over Japan (Kume, 1871-1873; Caprio, 2020). The Iwakura Embassy’s contemporary prominence in Japanese public memory is highlighted by the establishment of a park on the foreshore of Yokohama Port area that pays tribute to the execution of this extraordinary accomplishment.

Image 1. Iwakura Embassy Departure Image (author supplied)

Image 2. Japanese and English language description of the Iwakura Mission “Departure point of modernization of Japan” (author supplied)

Early Meiji Period

Domestically the powerful merchant houses that had been established during the earlier Tokugawa Period (also known as the Edo Period 1600-1868), like the nation itself, had split in their support/opposition to the Meiji elite’s Restoration of the young Emperor Mutsuhito in 1868, and so, not surprisingly, the new rulers of the nation felt no universal obligation towards enhancing this classes’ advancement (Cohen, 2014). As it would prove the Tokugawa merchant class was either reluctant to, or simply incapable of, supplying the vast levels of finances and human capital required for the new industrial infrastructure projects (such as railways and port-harbour facilities). These investment demands rendered short-term returns unlikely and further accentuated the gap between the new regime’s nation building industrial requirements and the private sectors capabilities (Sims, 2001:6-7). As a result, the Ministry of Public Works was established by the Meiji regime in the year of its founding, 1868, to promote the introduction of western technology into Japan and a loan was floated in the City of London, Great Britain’s center of banking finance, for the building of Japan’s first railroad-telegraph line – from Yokohama to Tokyo (Free, 2008). At this time any dialogue on railways, ports, the telegraph and others, like so much of the Meiji regime policy agenda, was in fact a proxy for the deep political domestic divisions centered on differing visions of the nation’s future, inclusive of the importation of ‘the foreign’ to secure modernity (Free, 2008; Walthall, 2018). As a result, a highly secretive meeting on the question of Japan’s first rail line was held at the house of Prince Sanjo Sanemtomi (1837-1891), Minister of the Right and acting-Premier, on December 7, 1869 (Vlastos, 1995). It would be between the very top echelon of the Meiji ruling elite, including Iwakura Tomobi (1825-1883) who as a long-time confident of the Meiji Emperor and future head of the famous 1871-1873 Embassy in his name (Caprio, 2020), and the British Minister to Japan, Sir Harry Smith Parkes (1828-1885: formal title Her Majesty’s Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary and Consul General for the United Kingdom to the Empire of Japan from 1865-1883) to decide the route options between: Tokyo-Yokohama; Kobe-Kyoto and Tokyo-Kyoto. At this time, and until the first decades of the next century, Great Britain was by-far Japan’s most important economic and industrial partner, a position Parkes vehemently promoted at every opportunity and that left neither the Japanese, the Americans, nor the continental Europeans, in any doubt of their own relative status (Keene, 2002). In the end, the Tokyo-Yokohama route was selected due to the rise of Tokyo as the political center of Japan, its commercial predominance, and the critically the flat alluvial geography that favored rail development (Free, 2008 Ch 3; Tang, 2014).

Irrespective of the route chosen, there remained deep concern within the government over hostility to the recruitment of the many foreigners needed for their expertise in rail projects development and execution (Plung, 2021). Reactionary forces made no secret of the fact that their tolerance of the modern and the foreign was limited. The ports, and the essential rail and telegraph developments, would be the most visible physical expression of the national changes taking place under the new regime, and hence ripe for both verbal and physical attack upon them. A rail spike hammered, even more so than in the West, was in Japan an avowedly political act (Chang, 1996, 2002; Low and Gooday, 1998; Tang, 2011; Ferguson, 2017; Kasza, 2018). Whilst in the former ports, rail and ocean-going steam vessels represented superiority in the form of the industrial revolution taking place, in developing nations like Japan which had yet to initiate such advancements this state-of-affairs represented an inferiority of their very being as both a people and a nation (Chang, 2002). The very fact that the Meiji state was able to successfully achieve national industrialization, development, and colonialism both disproved Social Darwinist European thinking, and rhetoric, and enabled the Meiji regime to project Japanese racial superiority and these same limitations upon their Asiatic neighbors (Sukehiro, 1988; Iriye, 1995; Zohar, 2020). The Meiji men never possessed doubts that they as Japanese could achieve the developmental levels of the Western powers; the 1860 exploits of the Kanrin Maru under the leadership of Admiral Yoshitake Kimura and his first Japanese-only crew to cross the Pacific having been a significant act of self-reinforcement. The only real question challenge in their mind was how fast they could catch up, and in doing so dispense with the unequal treaty system, so as to be on a fully equal sovereign-developmental footing with the European industrial powers.

To oversee not only the development of rail, but also the ports, mines and agrarian developments to complete the supply chain, and to secure the foreign expertise needed, the new Meiji government established a Ministry of Industry in December 1870 with the increasingly powerful figure of Ito Hirobumi (1841-1909) becoming its vice-minister in 1871 (Yoshitake, 1986; Takii, 2014; Caprio). Ito who had already travelled overseas as a student in London (1863) and to the United States of America to study currency (1870) would serve as one of Iwakura’s deputies throughout the Embassy. Based on the experience of Ito and others, young members of the Embassy would remain in the United States of America and European nations it would visit to undertake continuing formal studies on a wide array of areas identified as essential to the advancement of their nation (at institutions such as Rutgers College and the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis). These individuals, or others who had made their way to the America and Europe as individuals or within smaller missions and also stayed on, often for years, to study, would return to Japan in time to take up leading roles within the Meiji regime (for example Tanaka Fujimaro who after the United States would spent time touring several European countries examining education reform before returning to Japan in March 1873 to execute the resulting reforms through the Ministry of Education). Despite the new Ministry of Industry’s technical assistance, easy credit, and subsidies, the Meiji regime’s initial private-sector development drive throughout the early 1870s was a failure. Japan at this time was in every sense of the word a severely underdeveloped agrarian state in relation to the western powers, with the industrial structures and manufactures being defined as basic and of poor quality (Sukehiro, 1988; Sugiyama, 1994; Andressen, 2002; Cameron, 2007; Ferguson, 2001, 2004, 2017; Green, 2017). Many private sector enterprises simply went bankrupt due to a lack of human capital, financial management skills and broader knowledge of international industry and trade requirements. This private-sector failure left the Meiji elite with little choice other than to take an increasingly state-interventionist approach, including dramatically increasing its technical transfer commitments (Morris-Suzuki, 1994; Schuman, 2009; Studwell, 2013).

Building upon the already considerable skills of the Tokugawa artisans, technology was acquired and learned by the Meiji regime members through numerous other study missions abroad. Eighteen sixty had seen the first official Japanese mission of the Tokogawa regime to the United States of America and in particular the national capital of Washington D.C. to ratify a treaty on May 22 (1860), but it had been sent in near total secrecy, consisted of only a few members, and had very little impact domestically or internationally. The Iwakura Embassy of 1871 to 1873, in stark contrast, consisted of 70 members of the new regime, many of whom were already or would become significant figures within the Meiji regime for decades to come. Envoy Extraordinary Ambassador Plenipotentiary and Prime Minister Iwakura Tomomi, who as stated was a long time confident of the young Mutsuhito, was supported by four vice-Ambassadors who would themselves become national figures: Ito Hirobumi (1841-1909), Kido Koin (also known as Kido Takayoshi (1833-1877)), Okubo Toshimichi (1830-1878); and Yamaguchi Naoyoshi (1839-1894) (Kume, 1871-1873; Gluck in Miyoshi, 2005; Takii, 2014; Caprio, 2020). Far from being a secret mission, the Iwakura Embassy’s departure from Yokohama Port was openly celebrated by the regime (and as evidenced by Images 1 and 2, is still acknowledged as a seminal event in Japanese public history) as reflecting the nation’s moves towards sovereign equality and modernity. Indeed, the mission’s size, scale and duration abroad, unlike the Satsuma and Chosun secret missions to England in 1865, made any hope of keeping it secret from the regime’s enemies fanciful.2

The Iwakura Embassy would quickly come to recognize in Washington D.C. in the early months of 1872 just how unprepared they themselves and their nation were for any substantive revisions to the unequal treaty system (Kume, 1871-73; Auslin, 2004). In relation to the latter, obtaining vast amounts of information and knowledge on questions of economic modernity, such as the development of modern internal improvement such as ports and rail, the mission was an undeniable success. Visitors to the port of Yokohama can learn of the Iwakura Embassy’s departure through a small public park with several information boards, but that in no way can tell the whole story. As is the nature of any port the full story encompasses both those who have left, either permanently or to return, and those foreigners who either entered and remained, or themselves would depart Japan for other shores (Plung, 2021).

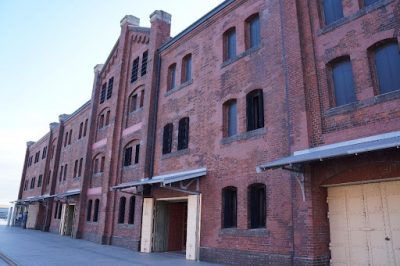

The obtaining of foreign knowledge through the mission would be insufficient, as a lone measure, and the Meiji regime had to at a very heavy cost import foreign technicians as educationalists rather than permanent advisers. For example, by 1879 the Ministry of Mines employed 130 foreigners whose salaries accounted for three-fifths of the ministry’s expenditure (Reischauer and Craig, 1989: 146-148; Miyoshi 2005: 178). The emphasis placed on the foreign advisers as educationalists-trainers made clear the Meiji leadership’s intent: those Japanese benefitting from the education-training were to take over these foreigners’ roles as soon as practically possible to avoid dependency (as evidenced in Images 3, 4, and 5 the influence of foreigners was, and remains, quite clearly visible against the traditional Japanese architecture). Such a stand fell within the broader political economy context of the regime itself with Japan having lost substantial elements of its sovereignty under the unequal treaty system and the Meiji leadership’s extensive knowledge of European and American colonialism in broader Asia3 (Iriye, 1995; Auslin, 2004; Pilling, 2014; Green, 2017; Zohar, 2020).

The monumental cost of the foreign advisors and the pressing need to establish economic development as a counterweight to the loss of sovereignty did result in substantive national development progress. For example, through the establishment of Regional Development Boards, most notably the Hokkaido Development Board (Kaitakushi) in 1871, the Meiji State undertook agricultural, fisheries, timber and mineral developments. All required the development of a national network of rails, ports, all-weather-roads, and communications developments in the form of the telegraph across both land and seas to secure these gains.4

Image 3. Kobe Akarenga Souko Red Brick Port Warehouses (author supplied)

Image 4. Yokohama Akarenga Souko “Red Brick Warehouse” (author supplied)Image 5. First Foreign Settlement Site (Yokohama) (author supplied)

Image 5. First Foreign Settlement Site (Yokohama) (author supplied)

During this era of small government, the period of 1885-1889 saw investment in fixed capital increase above 15 percent of total government expenditure, and 1.7 percent of the GNP. By the end of the period, 1910 to 1914, with the Meiji reign coming to an end in 1912, investment in fixed capital would rapidly expand to 27.7 percent of total government expenditure and 4.5 percent of the GNP (Yasuba and Dhiravegin, 1985: 21-25). This change was not ideologically driven but instead a pragmatic response on the part of the Meiji government elite to both domestic and international political, strategic, and economic imperatives (Cameron, 1997; Bix, 2000; Pyle, 2007; Teramoto and Minohara, 2017).

The Meiji Governing Elite

Substantial studies of the contemporary Japanese elite bureaucracy acknowledge that its key characteristics were all formed in the Meiji period (Beasley, 1988; Beasley, 1995; Koh, 1989; Johnson, 1982, 1995). The Ministry of Finance (MoF), established in 1868, the year of the Restoration, and the Ministry of Industry, established in 1881, have been the most-thoroughly internationally documented.5 Having observed through the seminal Iwakura Embassy and a series of smaller missions of the British, American, and German administrative elite, and in particularly those responsible for the national budgetary process, the Meiji regime framed its substantive reforms within the context of embracing the Confucian tradition. The Meiji elite moved to institute national civil-service examination system in 1880. For the Meiji elite this selection into their ranks via rigorous examination legitimised public officials with moral authority as servants of the Emperor to promote the public good including the development of internal improvements, state enterprises and the harnessing of ‘private’ enterprises deemed central to securing the nation’s sovereignty and prosperity (Johnson, 1982, 1995; Muchlhoff, 2014).

Having removed the samurai as a class and abolished their daimyo provincial loyalties, the Meiji elite redirected loyalty ties to the central bureaucracy as separate fiefdoms in themselves (Miyoshi, 2005: 91). Traditional clan loyalty based on geographic locations was, over the duration of the Meiji Emperor’s reign, to be replaced with another form of clan loyalty; one based on educational attainment, and which transcended government and found its way across all the nation’s major corporations in state banking, finance, rail, ports, manufactures and others (Fingleton, March/April 1995: 77). The Meiji state requirement to build the internal improvements needed to secure Japan’s rise in international stature saw the bureaucracy almost double between 1880 and 1890. Further from 1890 to 1903 administrative expenditure grew from 31 million to 121 million and government employees grew from 79,000 to 144,000 (Sims, 2001: 65 & 91-92). The continuity of Japan’s bureaucratic structures can be traced accurately (Johnson, 1995).

Under the 1890 Constitution’s diffusion of power, the system by which every ministry jealously guards its nawabari (sphere of influence) and all ministry members develop nawabari ishiki (territorial consciousness) was formally instituted. The primary vehicle for this institutionalisation of bureaucratic divisions were (and remain) intense competition over the national budget. At the apex of this new clan loyalty was the Ministry of Finance (MoF), the guardian of the nation’s finances through its control of the state budget. The 1890 Constitution institutionalised this MoF bureaucratic elite predominance as it placed a decisive limitation upon the powers of the Diet, one borrowed from Berlin in that if it failed to pass the national budget the government could continue its operation based on the preceding year’s budget (Storry, 1978). The MoF, in practice, held the whip hand over the Diet and would maintain the 1890 budgetary constitution to control the Meiji government apparatus with all other bureaucratic institutions and agencies required to pass their own ministry budgets through MoF scrutiny. All nation building projects, including the development of ports, rail, the telegraph, all-weather roads, the establishment of trade financing and logistics entities, all were either driven from, or required, the explicit approval and financing of the MoF. Critically, though it is important to understand that whilst the MoF stood at the apex of the Meiji regime bureaucratic hierarchy, it was ultimately under the authority of the Emperor. Mutsuhito more than once would show a willingness to reign-in his senior governing elite, including those overseeing the MoF, when he felt the state revenue-expenditure balance had reached a precipitous. This was particularly so during the first decades of his reign (1870s-1890s) (Keen, 2002). The MoF, nevertheless, went further than mere mastery over the bureaucracy and established its grip over the national economy through embedding its alumni into the nation’s major state and ‘private’ corporations, inclusive of the banking and trade entities that drove Japan’s engagement with the world, as a continuation of their loyalty to their Emperor and by extension their MoF clan (Patrick, 1965; Hoshi and Kashyap, 2001).

The rise of the MoF was not ideological but strategically pragmatic as it was only utilised when it was deemed essential to the national interests, with the Meiji elite preferring to use the private sector where applicable and to engage in state intervention through the MoF and other Meiji agencies for the building of rail and ports only when the market proved itself incapable of delivering nation-building. A working model of private-driven rapid nation-building economic development, however, did not present itself. The MoF’s direct control over an economic base independent of the private sector, including the banking sector and a vast array of state-owned enterprises, provided the bureaucratic elite with strategic control over capital, materials, labour and national economic planning (Chu, 1994:118). Ex-officials from the MoF would come quickly to dominate the executive level within both public and ‘private’ financial, internal improvements, rail, ports, roads, the telegraph, and other institutions (institutions such as the Japan Development Bank (JDB); Export-Import Bank of Japan (EIBJ); Tokyo Stock Exchange; Bank of Tokyo; Yokohama Bank; and others). Japan’s action in fact mirrored those of London, Berlin and Washington D.C., in that they pragmatically evaluated their own contextual environment and circumstances and adopted, adapted and developed old and new policy and practice models and behaviors to achieve eventual success. As this study has detailed the Meiji men observed and extensively documented first-hand through the Iwakura Embassy and other smaller missions the development of the advanced western states public policy-financial-industrial-trading practices and institutions, and quickly came to conclude that far from being the product of Adam Smith’s invisible hand of the market, the international powers’ predominance in arms, finance and trade was in fact the product of the long-term concerted actions of the respective state-activist elites driving these respective nations (Kume, 1871-1873; Fukui, 1992; Iriye, 1995; Takii, 2014).

Ports, Shipping, Railways and Communication

In recognition of their military importance to Japan, the Meiji elite developed railways, shipping and communication services (domestic and international postal services/telegraph) through the use of both government-and-private enterprises to achieve projects of national significance. For example, Emperor Mutsuhito himself took a deep personal interest in every aspect of Japan’s development of a deep-water navy, with Japan’s first western battleship being purchased from the United States of America. This was hardly surprising when one considers that it was the naval power of the United States of America, Great Britain and other western powers that completely discredited the Tokugawa regime’s capacity to protect the nation and therefore its legitimacy to rule. Mutsuhito’s studies extended to undertaking extensive personal studies of both western powers’ battleship developments and the required internal improvement, such as corresponding deep-water ports and the rail networks needed to supply the coal, iron ore, timber and other resources, along with the construction and maintenance of these colossal state investments (Keene, 2002). In this, the Meiji Emperor and his leading men were systematic in following the actions of the United States, Britain and continental Europe, actions many themselves had witnessed first-hand through extensive study tours (Kume, 1871-1873). The Railway Construction Act of 1892 coordinated a national network which rose in the 1883 to 1903 period from 245 miles to 4,500 miles, with 70 percent being constructed by private-enterprise, and, in 1906, state ownership was secured through the Railway Nationalisation Bill (see Table).

Image 6. Cornerstone/foundation stone of the Port of Yokohama (author supplied)

Along with this rapid development in internal improvement, a similar pattern of incentives and penalties was used in ports, rail, shipbuilding, communication, electrical industries, textiles, low-end tool manufactures, steam-machinery and later chemical, metal products, and machinery. Through the direct import and development of British technology, the textile sector (at first silk production and exportation), in particular, expanded to occupy nearly 30 percent of value-added manufactures throughout the 1890 to 1930 period, the next largest, at 16 percent, was food and drink (Beasley, 1995: 110; Reischauer and Craig, 1989: 149). Under the new Meiji policy-loan scheme the increase in the share of total manufacturing output in the GDP grew from 13.7 percent in 1873-1874 to 43.7 percent in 1930-1939. Furthermore, through sustained technological importation and innovation, manufacturing rose from 6 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) by 1900 to 30 percent by 1945. Fukui, 1992: 202.

Image 7. Public history of Yokohama’s original railway service between Yokohama and Shinagawa, displayed at Sakuragicho Station (author supplied)

Image 8. C11 292 steam locomotive outside Shimbashi Station, Minato (author supplied)

Table: Meiji Infrastructure Development 1868-1912: Transportation (Rail, Ports and Steam Vessels) and the Communications Revolution (the Telegraph) takes shape Japan.

- National-Political: Rail, Ports and the Telegraph would tie the nation together and enabled the Meiji regime through a network of rail-telegraph to expand its reach into the most remote of villages. The Meiji elite coming from isolated regional provinces themselves fully understood the political importance of rapid and effective communication from the centre to the periphery, and vice versa to the permanency of their regime.

- The first railway link, from Tokyo to Yokohama, was solely government-funded under the Japan Railway Company (Nihon Tetsudo Kaisha) which itself was under the Ministry of Civil Affairs, with material-and-technical services provided by Great Britain. The budget was a truly astronomical £300,000 with British technology and expertise predominant, yet construction quality was often poor because of the inexperience of the Japanese workforce who would learn-by-doing. It would be an outright success with its first full year of operation 1873 (indecently 43 years after rails introduction in Britain): 1, 223,071 passengers: ¥395,988 in revenue with costs of ¥117,879. Frequency increased from 6 to 9 times daily: Freight was introduced in September 1873 (Free, 2008).

- The Tokyo-Yokohama would see travel and transportation times in Japan go from 20 miles a day to 20-35 miles an hour. Japan had moved from the human-horsepower era that had existed for millennia into a new era of steam. In contemporary terms it was the equivalent to the quantum advancements taking place in relation to private enterprise space travel. An American R. P. Bridgens would be the foreign specialist architect who designed the original Shimbashi and Yokohama stations (Free, 2008).

- The Kobe-Osaka-Kyoto line would be next and by December 1871 the survey line had been staked-out. In December 1873 authorization to begin construction of the line was given and involved extensive infrastructure development within the Kobe port itself and a series of through wrought iron river crossing bridges to be constructed. The Kobe-Osaka link was finalized in May 1874 and was extended further to Kyoto in September 1876.

- National-Strategic: The rail-ports-telegraph nexus would enable the movement of Imperial troops, arms and other military resources across the nation in the most efficient manner possible to crush any domestic uprisings. The Meiji men were more than aware through extensive studies of the decisive role rail had played in delivering the Union military victory over the Confederacy in the American Civil War (1861-1865) and the increasing role of rail in continental European conflicts, including Bismarck’s decisive use of rail in the Franco-German War of 1870.

- The critical role of rail-ports-telegraph in delivering strategic power would come to full fruition domestically when it proved decisive in crushing the Satsuma rebellion in 1877. The Meiji regime victory, and in particular the capacity of the Imperial Army and Navy to deliver unprecedented levels of men, arms and other resources to the battlefield through rail, ports and the telegraph, ended internal rebellion.

- The crushing of the Satsuma Rebellion was to be the logistical schooling the Meiji regime would utilise for Japan’s movement of troops and resources via the development and advancement of rail, ports, the telegraph and steam-powered ocean-going vessels to Taiwan, Korea, Southern Manchuria, and China in the coming decades (Chang and Myer, August 1963). The port-rail-telegraph developments that had taken place throughout the 1870s-1780s would be replicated by Meiji men in these new colonial territories for the advancement of their nation’s interests.

- In 1887, private capital was attracted by extending State assurances of capital return through railway-monopoly licenses, and re-nationalisation after twenty-five years.

- The Railway Construction Act of 1892 saw the national network rise from 245 miles (1883) to 4,500 miles (1903), with 70 percent being constructed by private enterprise.

- In 1906, state ownership was secured through the Railway Nationalisation Bill (Crawcour. 1988: 394).

The Telegraph

- Commodore William Perry on his second trip to Japan in 1854 (Iokibe and Minohara, 2017) presented the Tokugawa shogunate with an embossing Morse Telegraph transmitter:

“After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, government leaders quickly decided to make the establishment of a telegraph service one of their top priorities. Two years later, a telegraph service between Tokyo and Yokohama was provided for the general public. The telegraph service expanded rapidly, and a nation-wide network was completed by 1878. Members of the Embassy (1872) were eager to meet and honour Morse; to their deep regret, he was taken ill and died while they were in Washington” (Editors in Kume, 1871-1873 Vol. 1: 80).

- In mid-1872 a new telegraph line from Nagasaki to Shanghai to London to New York meant that news from Tokyo was quickly transmitted to Nagasaki and onto the rest of the world. An event in Tokyo could now be reported within a New York or Dutch newspaper 2 days later and vice versa. The Meiji Emperor and his inner circle were now able to be fully informed of events globally, most importantly strategic and military events amongst the great powers, like never before and would respond to these with new policies and initiatives reflective of the new speed of information.

- Between 1883-1913 post offices rose from 3,500 to 7,000; 2.7 million telegrams in 1882 rose to 40 million in 1913; telephones which were introduced in 1890 with 400 subscribers and only two exchanges, by 1913 reached 200,000 subscribers with 1,046 exchanges. The government backed Tokyo Electrical Company expanded from 21,000 lamps in 1890 to 5 million in 1913 (Sydney, 1988: 394).

Image 9. Plaque commemorating the centenary of the commencement of international postal service from Yokohama Port (author supplied); 5-3 Nihonodori, Naka Ward, Yokohama, Kanagawa 231-8799, Japan.

Meiji International Trade Policy

Japan’s international trade policy, as an extension of its national elite’s ideology of Kokutai and broader industrial policy, has enjoyed continuity. Japan’s Meiji leaders and their successors have been “well aware that the country’s power and prestige were hostage to its ability to promote foreign trade” (Duus, 1988: 25). Unless Japan could undertake expansion of its manufacturing industries and sell its goods in the world market, it could not acquire the armaments and materials needed to secure its hold on power, and in time its expanding empire. The Japanese elite pragmatically acknowledged that they operated in a mercantile international environment dominated by the trading powers of Great Britain, The United States of America and continental Europe (Young, 1877-1879). Following the precedent set by Prussian/German administrators, export credit secured primarily through special banks operating under the purview of the MoF was utilised by the Meiji elite to achieve rapid trade development. The Meiji regime instituted export associations, establishing the Yokohama Specie Bank (1892) to facilitate foreign exchange transactions, subsidise export industries, strengthen consular economic reporting and construct an ocean-going merchant marine.

The Meiji elite divided trade strategy and the world into two separate spheres: one for trade and one for conquest. From the industrial world (Britain, Europe and the United States), it sought to acquire manufacturing technology and semi-manufactured goods and, in return, export primary goods (silk and tea) and labour-intensive craft products (Chang 1996, 2002). To the non-industrial world, primarily their Northeast and Southeast Asian regional neighbours, the Meiji elite in the early years of the regime sought to export inexpensive light-industry products, such as cotton, textiles and other assorted manufactured goods, and, in return, purchase raw materials and foodstuffs. In time through its colonial actions against it near-neighbours this process would be one of forced distribution and acquisition (Chang, 1963; Duss, 1995; Zohar, 2020; Tinello, 2021). While introducing importation regulations that assured technological transfer in relation to value-added products, the Meiji state advocated the open importation of raw materials for manufacturing. This is hardly surprising, as, with its limited-resource base, Japan found it imperative to maintain an open raw-material trade/forced acquisition (Yoshitake, 1986; Iriye, 1995; Teramoto and Minohara, 2017). Images 10 and 11 represent enduring examples of the early infrastructure through which the Meiji trade strategy was made possible. The Meiji men would make full use of their predecessor’s connections with the Dutch trading empire, utilising this knowledge as a platform upon which to build relations with the British Empire, United States of America, and continental European powers (as Image 11 depicts).

Image 10. Pictograph along the Nakashima River of the Nagasaki Canal Trading and Warehouse system (author supplied); 8 Uonomachi, Nagasaki, 850-0874, Japan.

Image 11. Current construction HSBC, built 1904, Former site Dutch Trading Quarters Nagasaki Dutch Trading House (author supplied); 4-27 Matsugaemachi, Nagasaki, 850-0921, Japan

Japanese shipping would begin regular trade throughout East and Southeast Asia in the 1880s and with it came the Keiretsu, state banks and consular offices, all supported by the State Japanese Associations (Nihonjinkai). The easy-credit terms Japanese banks extended to Chinese enterprises ensured that, unlike their western counterparts, Japanese enterprises secured the Chinese-business networks throughout Southeast Asia. At the same time (1880s-90) the international-trade climate saw the major developed countries, including the United States, Britain and Germany, turn their backs on the limited free trade regime in existence and instead engage in increasing levels of mercantile public policy. This macroenvironmental shift in global trading conditions in turn forced the Meiji regime to maintain state finance-trade intervention in the form of extending finance across state-owned port, rail, telegraph, merchant marine and other trade-oriented development (Hoshi, 1995; Bix, 2000).

Japan’s Meiji leaders, having come to power as a direct response to their Tokugawa predecessor’s failure to maintain trade sovereignty in the face of the western imposed unequal treaties (1854 onwards), were “well aware that the country’s power and prestige were hostage to its ability to promote foreign trade” (Duus, 1988: 25). The Meiji elite having been the subject of western superior naval arms understood that unless Japan could sell its goods in the world it could not acquire the arms (modern rifles, artillery and shipping) needed to protect itself, enact its own sovereignty, and when possible, establish a future East Asian empire designed to enable a mass expansion of manufacturing and heavy industries. Only a network of domestic and regional port-rail-telegraph and other internal improvement infrastructure could secure this, and so, they were deemed to be nation-building projects by the Meiji men who cared little if they were enacted under either state or private activism but cared entirely that they come to timely fruition.

Image 12. Pictograph of the second arrival of Commodore Perry to Yokohama, located outside of the ‘Yokohama Archives of History’ Building (author supplied)

The Meiji elite divided trade strategy and the world into two separate spheres. From the industrial world (Britain, the United States and continental Europe), it sought to acquire manufacturing technology and semi-manufactured goods and from the non-industrial world (primarily its Asian regional neighbours) it purchased raw materials and foodstuffs. Even before it established itself as colonial ruler of Taiwan in 1890, and later Korea in 1910, through state-financing Japanese shipping began regular trade throughout East Asia in the 1880s. Doing so through its forced acquisition of the Loo-Choo Islands (incorporated into the Okinawa Prefecture) in the late-1870s (Shuman, 2009; Studwell, 2013; Pilling, 2014; Ch’oe, 2015). With the Meiji-elite-driven expansion of East Asian shipping trade came further state-support for the Keiretsu trade enterprises via State banks, extensive consular offices and officials and a network supported through the State Japanese Associations (Nihonjinkai). The Japanese elite from 1868 until 1912 and onwards then pragmatically acknowledged the obvious; that they operated in a mercantile international environment dominated by the trading powers of Great Britain, the United States of America and an expansionary Germany, all of whom had either taken colonies or trade-concessions in the East Asian region (Tinello, 2021; Caprio, 2020; Zohar, 2020).

Conclusion: Meiji Japan’s Emergence as a World Economic Power

The images presented in this paper highlight and corroborate a public historical analysis enshrined in the enduring physical manifestations of the efforts of the Meiji government’s concerted nation building. These physical manifestations are critically important to understanding the history of Japan’s rise to developed nation status, but do not in of themselves tell the entire story of domestic political power struggles that themselves derived from the international powers’ dynamics, inclusive of being both subjected to and the executor of colonialism, occupation, and coercion, and eventually efforts toward full sovereignty. Contemporary Japanese society would not be possible without the efforts represented by the physical manifestations of Meiji history, which remain visible if even presented as a largely silent history to the citizens of Japan and its many visitors.

Japan, like all the other colonial powers, in extending its imperial ambitions defined its self-serving actions as very much within the ‘norm’ of international affairs (Ch’oe, 2015). Unlike the other colonial powers, however, it did so whilst it itself was the subject of colonialism in the form of the western state imposed unequal treaty system. Under such an international paradigm, the full restoration of national sovereignty stood at the apex of all state thinking and policy activity. The physical creation of import-export banks, ports, railways, postal and telegraph networks and vast internal improvements across the Japanese landscape being not an economic imperative in themselves but instead were the manifestation of the core national geo-political strategic directive: the restoration of the full sovereignty of the nation under the Emperor’s rule.

Even with Meiji-European powers treaty revisions in the first decade of the twentieth century, that restored much of the sovereignty Japan had long been denied, equality between the rising Asian power and the established international powers would prove elusive. The western powers, even after the Japanese Navies’ defeat of Russian forces in 1905, held firm on the belief that they held ascendancy within the international realm in perpetuity (Kowner, 2022). To do otherwise was to acknowledge that it was not their race and their belief in the inherent superiority, it bestowed upon them, that made colonialism a legitimate act of international public policy but simply their current position within the industrial revolution that delivered to them superior arms: and this the western powers simply could not do. Their entire domestic and international regimes, inclusive of political, economic and social structures, relied upon this self-perception of racial superiority. This race-developmental advancement nexus would be no less the case than with the Meiji men as they commenced Japan’s construction of its East Asian sphere of influence, and their successors drive towards war across Asia and ultimately unconditional defeat in 1945 (Chang and Myer, 1963; Duus, 1995).

The success of the Meiji regime elite in placing Japan on the road to unprecedented rapid economic development is for all to see in the public history displayed within the port districts of Yokohama, Kobe and Nagasaki. Silence marks the history of how important these port-rail-communications developments were to the restoration of Japan’s own sovereignty and the simultaneous stripping away of others. As stated above these developmental achievements were the product of the larger goal of national sovereignty and crucially were the product of the Meiji elite being left to its own domestic reform agenda. Whilst limited in key areas because of the western powers imposition of the unequal treaty system, the Meiji men were able to implement public policy that was ultimately pragmatic, quickly altering policies when they proved to be detrimental to state building and economic development and pursuing with vigour those deemed essential to national sovereignty and security (Kume, 1871-1873; Yoshitake, 1986). In the international realm the ports-rail-telegraph nexus would prove critical to enacting colonialism over Taiwan and Korea largely uninterrupted from western power interference, and further into Manchuria and China which in stark contrast met with fierce western powers resistance (Ch’oe, 2015; Teramoto and Minohara, 2017).

International events would be critical to the Meiji regime’s thinking, and as military men themselves they keenly observed success in this field, so they took particular interest in the European powers’ colonial actions towards China from the 1840s onwards, the Union victory over Southern secessionist during the American Civil War (1861-1865) and Bismarck’s Prussian army’s crushing of France (1870-1871). In fact, the lesson of western might and power came to these men on their own shores. Whilst the industrial superior Union was at war with its rebellious southern countrymen it also made time in 1864 to join a flotilla of western naval power consisting of Britain, France, the Netherlands and itself to comprehensively dismantle the defences of the Choshu domain through sheer superior arms. In the year prior (1863) the British Royal Navy alone had bought the Satsuma domain to a position of forced negotiation. It was no accident that it was from these two domains, Satsuma and Chosun, that the majority of the Meiji regime men heralded from. The clear and unequivocal message from the western naval submission of Satsuma and Chosun and international events such as China’s humiliation at the hands of the industrial western powers and the Lincoln-led industrial northern victory over the southern plantocracy was the same: to remain an agrarian society was for Japan to be in perpetuity a mere pawn to the western financial-industrial nation-states. Put simply they acknowledged that you either became a power within the international realm, or you became a vassal state: with no real space in-between (Yoshitake, 1986; Morris-Suzuki, 1994; Fallows, 1995; Caprio, 2020; Zohar, 2020; Tinello, 2021).

The Meiji regime, therefore, would forge a trading system of export-financing, port infrastructure, rail and postal services/the telegraph celebrated today in public memory, that itself relied on the development and the strengthening of the state institutional capacity (governance, public policy execution, financial institutions, legal structures, private incentive systems, human-capital development and others) to ensure that this fate did not befall the Japanese nation (Masuyama, 1999: 16). The Meiji men did not require any theoretical exploration as to the essential nature of infrastructure development to their nation and their regime’s future. They themselves had been subjected to the power that the western industrial states could extend globally through their development of ports, rail and the telegraph, whilst their massive near regional neighbor, China, was experiencing its nineteenth century fate of being picked apart by the European powers precisely because of the collective failure of that nation’s leadership to execute effective internal improvements that would have enabled a large modern Chinese army and navy and resources through rail, port and communications (telegraph and other) developments to strategically counter this foreign encroachment.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Dr Ian Austin is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Business and Law, Edith Cowan University in Perth, Western Australia. He is the author of four manuscripts and two co-authored works on East Asian public policy and economic development. He has worked extensively in Asia for two decades.

Alexander Best is a PhD student and Sessional Academic at the School of Business and Law, Edith Cowan University in Perth, Western Australia. He holds a Bachelor of Event, Sport and Recreation Management (Hons), and a Diploma of Language Studies (majoring in Japanese), which he completed as an Australian Government-awarded New Colombo Plan Scholar (2016) based in Kyoto, Japan.

Sources

Andressen, Curtis. (2002). A Short History of Japan: From Samurai to Sony. Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest NSW.

Auslin, Michael R. (2004). Negotiating with Imperialism The Unequal Treaties and the Culture of Japanese Diplomacy. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: Harvard University Press.

Beasley, W.G. (1988). “Meiji Political Institutions”. in Duus, Peter. ed. 1988. The Cambridge History of Japan: Volume 5 The Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 618-673.

Beasley, W.G. (1995). The Rise of Modern Japan: Political, Economic and Social Change Since 1850. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Bix, Herbert P. (2000). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. HartpersCollins: New York.

Campbell, Edwina S. (2016). Citizen of a Wider Commonwealth: Ulysses S. Grant’s Post-presidential Diplomacy. Carbondale, Il. Southern Illinois University Press.

Cameron, Rondo. (1997). A Concise Economic History of the World: From Paleolithic Times to the Present.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Caprio, Mark. (2020) Oct 15. “To Adopt a Small or Large State Mentality: The Iwakura Mission and Japan’s Meiji-era Foreign Policy Dilemma”. The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus. 18, 20, 3, Article ID 5497.

Chang, Ha-Joon. (1996). The Political Economy of Industry Policy. 2nd ed. New York: St. Marin’s Press.

Chang, Ha-Joon. (2002). Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective. London: Anthem Press.

Chang, Han-Yu and Ramon H. Myer. (1963) Aug. “Japanese Colonial Development Policy in Taiwan, 1895-1906”. The Journal of Asian Studies. 22(4). pp. 433-449.

Ch’oe, Yong. (2015) Mar 2. “Japan’s 1905 Incorporation of Dokdo/Takeshima: a Historical Perspective”. The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus. 13. 9. 3. Article ID 4290.

Cohen, Mark. (2014). “The political process of the revolutionary samurai: a comparative reconsideration of Japan’s Meiji Restoration”. Theory and Society. 43. 2: 139-168.

Duus, Peter. ed. (1988). The Cambridge History of Japan: Volume 5 The Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Duus, Peter. (1995). The Abacus and the Sword The Japanese Penetration of Korea, 1895-1910. Berkley: The University of California Press.

Ferguson, Niall. (2001). The Cash Nexus: Money and Power in the Modern World, 1700-2000. London: Penguin Books.

Ferguson, Niall. (2004). Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire. Penguin Books: New York.

Ferguson, Niall. (2017). The Square and the Tower: Networks, Hierarchies and the Struggle for Global Power. Allen Lane and imprint of Penguin Books: Milton Keynes.

Free, Dan. (2008). Early Japanese Railways 1853-1914 Engineering Triumphs That Transformed Meiji-era Japan. Tuttle Publishing: Tokyo, Rutland, Vermont, Singapore.

Fukui, Haruhiro. (1992). “The Japanese State and Economic Development: Profile of a Nationalist-Paternalist Capitalist State”. in Appelbaum, Richard P. and Jeffrey Henderson. eds. 1992. States And Development in the Asian Pacific Rim. London: Sage Publications. pp. 199-225.

Giffard, Sydney. (1994). Japan Among the Powers 1890-1990. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Green, Michael J. (2017). By More than Providence Grand Strategy and American Power in the Asia Pacific Since 1783. A Nancy Bernkopf Tucker and Warren I. Cohn Book on American-East Asian Relations. Columbia University Press: New York.

Holcombe, Charles. (2011). A History of East Asia From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press: New York.

Hoshi, T., & Kashyap, A. K. (2001). Corporate financing and governance in Japan: The road to the future. The MIT Press.

Iokibe, Makoto and Tosh Minohara. (2017) English Edition (Japan original 2008). “Chapter 1: American Encounters Japan, 1836-94”. in Iokibe, Makoto and Tosh Minohara, Editor and English translation editor respectively. (2017) English Edition (Japanese original 2008). The History of U.S.-Japan Relations: From Perry to the Present. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 3-22.

Iriye, Akira. (1995). “Japan’s drive to great-power status”. in Jansen, Marius B. ed. 1995. The Emergence of Meiji Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 268-330.

Jansen, Marius B. ed. (1995). The Emergence of Meiji Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, Chalmers. (1982). MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Johnson, Chalmers. (1995). Japan: Who Governs? – The Rise of the Developmental State. London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Kasza, Gregory J. (2018) June. “Gerschenkron, Amsden, and Japan: the State in Late Development”. Japanese Journal of Political Science. 19 (2): 146-172.

Keene, Donald. (2002). Emperor of Japan Meiji and His World 1852-1912. New York: Columbia University.

Kowner, Rotem. (2022) June 15. “Time to Remember, Time to Forget: The Battle of Tsushima in Japanese Collective Memory since 1905”. The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus. Volume 20 | Issue 12 | Number 3. Article ID 5716.

Kume Kunitake. (1871-73). The Iwakura Embassy 1871-73: A True Account of the Ambassador Extrordinary & Plenipotentiary’s Journey of Observation Through the United States and Europe. Vol. 1-5. (Editors-in-Chief Graham Healey & Chushichi Tsuzuki, 2002: Tanaka Akira. (2002). “Introduction”).

LaFeber, Walter. (1997). The Clash: U.S.-Japanese Relations Throughout History. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Low, M. and Gooday, G. J. (1998). “Technology transfer and cultural exchange: Western scientists and engineers encounter late Tokugawa and Meiji Japan”. Osiris 13 99-128.

Masons, R.H.P. and J.G. Caiger. (1972). “The Meiji Era and Policies of Modernisation”. A History of Japan. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle. pp. 213-255.

Miyoshi, Masao. (2005). Foreword by Carol Gluck. As We Saw Them The First Japanese Embassy to the United States. Philadelphia: Paul Dr Books.

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. (1994). The Technological Transformation of Japan: From the Seventeenth to the Twenty-first Century. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Muchlhoff, Katharina. (2014). “The economic cost of sleaze or how replacing samurai with bureacrats boosted regional growth in Meiji Japan”. Cliometrica. 8: 201-239.

Najita, Tetsuo. (1974). Japan: The Intellectual Foundations of Modern Japanese Politics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Patrick, Hugh T. (1965). External Equilibrium and Internal Convertibility: Financial Policy in Meiji Japan. The Journal of Economic History. 25. 2 (June): 187-213.

Pilling, David. (2014). Bending Adversity Japan and the Art of Survival. New York: The Penguin Press.

Plung, Dylan J. (2021) Apr 15. “The “Unrelated” Spirits of Aoyama Cemetery: A 21st Century Reckoning with the Foreign Employees of the Meiji Period”. The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus. 19, 8, 1. Article ID 5567.

Pyle, Kenneth B. (2007). Japan Rising The Resurgence of Japanese Power and Purpose. New York: Public Affairs.

Reischauer, Edwin O. and Albert M. Craig. (1989). Japan: Tradition and Transformation. St Leonard: Allen and Unwin.

Samuels, Richard J. (1994). Rich Nation Strong Army: National Security and the Technological Transformation of Japan. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Sims, Richard. (2001). Japanese Political History since the Meiji Renovation: 1868-2000. London: Hurst & Company.

Schuman, Michael. (2009). The Miracle The Epic Story of Asia’s Quest for Wealth. New York: Harper Collins.

Studwell, Richard. (2013). How Asia Works Success and Failure in the World’s Most Dynamic Region. London: Profile Books.

Sukehiro, Hirakawa (translated by Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi). (1988). “Japan’s Turn to the West”. in Duus, Peter. ed. (1988). The Cambridge History of Japan: Volume 5 The Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 432-498.

Sugiyama, Chuhei. (1994). Origins of Economic Thought in Modern Japan. New York: Routledge Press.

Takii, Kazuhiro (translated by Takechi Manabu, edited by Patricia Murray). (2014). Ito Hirobumi Japan’s First Prime Minister and the Father of the Meiji Constitution. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

Tang, John. (2011) Sept. “Technological leadership and late development: evidence from Meiji Japan, 1868-1912”. Economic History Review. 64, No. 1: pp. 99-116.

Tang, John. (2014) Sept. “Railroad Expansion and Industrialization: Evidence from Meiji Japan”. The Journal of Economic History. 74, No. 3: pp. 863-886.

Teramoto, Yasutoshi and Tosh Minohara. (2017) English Edition (Japanese original 2008). “Chapter 2: The Emergence of Japan on the Global Stage, 1895-1908. in Iokibe, Makoto and Tosh Minohara, Editor and English translation editor respectively. 2017 English Edition (Japan original 2008). The History of U.S.-Japan Relations: From Perry to the Present. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 23-42.

Tinello, (2021), Mar 15. “Early Meiji Diplomacy Viewed through the Lens of the International Treaties Culminating in the Annexation of the Ryukus”. The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus. 19. 6. 2. Article ID 5558.

Walthall, Anne. (2018). “The Meiji Restoration Seen from English Speaking Countries”. Japanese Studies. 38. 3: 363–376.

Yasuba, Yasukichi and Likhit Dhiravegin. (1985). “Initial Conditions, Institutional Changes, Policy, and their Consequences: Siam and Japan, 1850-1914.” in Ohkawa, Kazushi, Gustav Ranis and Larry Meissner. eds. 1985. Japan and the Developing Countries: A Comparative Analysis. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Yoshitake, Oka. (Translated by Andrew Fraser and Patricia Murray). (1986). Five Political Leaders of Modern Japan: Ito Hirobumi, Okuma Shigenobu, Hara Takashi, Inukai Tsuyoshi, and Saionji Kimmochi. Tokyo: Tokyo University Press.

Young, John Russell. (1877, 1878, 1879). Around the World with General Grant. A Narrative of the Visit of General U.S. Grant, Ex-President of the United States, to Various Countries in Europe, Asia and Africa in 1877, 1878, 1879 to which added Certain Conversations with General Grant on Questions Connected with American Politics and History. Volume II. New York: Subscription Book Department. The American News Company.

Vlastos, Stephen. (1995). “Opposition movements in early Meiji, 1868-1885”. in Jansen, Marius B. ed. 1995. The Emergence of Meiji Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 203-267.

Zohar, Ayelet. (2020), Oct 15. “Introduction: Race and Empire in Meiji Japan”. The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus. 18. 20. 2. Article ID 5496.

Notes

1 The authors of this work would like to thank Professor Mark E. Caprio of Rikkyo University, Japan, for his review of the paper which contributed to its improvement in every sense.

2 Under the Tokugawa regime unauthorised travel abroad saw the death penalty applied to anyone who returned home. Even those who made no conscious decision to leave, like fishermen swept away from Japan by vicious storms found themselves having to reside on foreign soil, never able to return under fear of execution.

3 On July 29th, 1858 the Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the United States had been signed on the U.S. Frigate Powhatan in Edo Bay with the inequity in military power between the two actors being abundantly clear to all.

4 Nagasaki, Hiroshima, Kobe, Yokohama, Aomori, Hokkaido and other ports development, and Japan’s connection to the international trans-oceanic telegraph cable all proceeded apace under Meiji governance.

5 Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) and Ministry of Finance (MoF).