Japan’s World Heritage Miike Coal Mine – Where Prisoners-of-war Worked “Like Slaves”

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @crg_globalresearch.

***

Abstract

Mitsui’s Miike Coal Mine is World Heritage listed by UNESCO as one of Japan’s “Sites of the Industrial Revolution.” The Japanese government, however, has failed to tell the full story of this mine, instead promoting bland tourism. In World War II, Miike was Japan’s largest coal mine, but also the location of the largest Allied POW camp in Japan. Korean and Chinese forced laborers also were used by Mitsui in the mine. The use of prisoners was nothing new, as Mitsui and other Japanese companies used Japanese convicts as workers in the early decades of the Meiji era. The role of Australian POWs in particular reveals that there was resistance inside Miike even at the height of abuse by Japanese wartime authorities. Japan has a responsibility under its UNESCO World Heritage agreement to tell the full history of this and other “Meiji Industrial Revolution” sites.

*

“As we passed through the gates [on January 16, 1945] we saw a few Japanese soldiers grouped about a charcoal brazier in the open porch of a small building. … It seemed that this was the largest prisoner-of-war camp in Kyushu, if not in Japan. … The camp held four nationalities: English, American, Dutch and Australian. … We were warned that our existence in and out of camp was governed by a multitude of rules and regulations. … Whenever we met one of the Australians who had been in the camp before our arrival and worked in the mine, we asked the same questions but could never get an accurate picture of what the mine was like down below. We only learnt we’d ‘work like slaves’.” – Private Roy Whitecross, 8th Division, Australian Army1

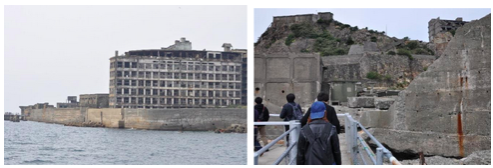

In July 2021, Japan’s public presentation of its “Sites of the Meiji Industrial Revolution” at the UNESCO World Heritage Committee annual meeting may be challenged. Among the sites possibly under question are two undersea coal mines that have been closed for decades: Mitsubishi’s former Hashima Coal Mine, popularly known as “Battleship Island” (Gunkanjima in Japanese) off the coast of Nagasaki; and Mitsui’s former Miike Coal Mine in Omuta, some fifty kilometers from Nagasaki city, or about an hour by car around the Ariake Sea in Kyushu.

Japan has succeeded in making Gunkanjima a huge tourist attraction, with over a quarter of a million visitors in 2015, the year it was inscribed as a World Heritage site.

The 2012 James Bond movie Skyfall featured a cameo scene of Gunkanjima, the villain’s secret island headquarters. A major South Korean history action film followed in which

Korean forced laborers destroyed the Japanese authorities in a fantasy liberation of the island in wartime.2In contrast, Miike Coal Mine and its Omuta harbor connection have thus far failed as a tourist draw, accounting for very low visitor numbers. Local online publicity that highlights smiling Japanese Miike miners traveling underground to the coal face lacks the popular drama of the huge island ghost city of Gunkanjima. But the true history of miners at the Miike Coal Mine over the century of its operation (1870s to 1997 closure) is just as dramatic as that of the Gunkanjima mine. Unfortunately the Japanese government omits most of this history at the Miike Mine.

Omuta local tourist website. The photo of these Japanese miners was probably taken in the late 1950s, before the 1960 strike – Japan’s largest strike in the postwar era. There are no tours underground.

Tourists arrive at Gunkanjima / Battleship Island, Mitsubishi’s former undersea coal mine – one of the World Heritage listed “Japan’s Sites of the Meiji Industrial Revolution”. Almost all buildings in these photos were built after Meiji, during the 1920s and 1930s. Photos by David Palmer.

The irony is that if the Japanese government told the true story of the Miike Mine itr could substantially reverse this tourism failure, as this coal mine was not only the largest in Japan in World War II, essential to its wartime economy, but also had the largest Allied POW camp in Japan – Fukuoka 17 – along with thousands of Korean and Chinese forced laborers, making it the largest “prisoner of war” operation within Japan.

What drives the distorted narrative of the Japanese government is its prioritizing tourism that focuses on machinery combined with a nationalism that portrays Japanese workers who enjoy their jobs, but without any mention of substantial forced labor. For decades tourism has been a major part of Japan’s economy, and World Heritage site listings are an important part of the government’s economic strategy to expand tourism, especially international tourism. In 2019, the year before the pandemic closed most tourism in Japan except to Japanese, World Economic Forum ranked Japan fourth globally in travel and tourism competitiveness.3 Japan’s tourism that year constituted 7.5 percent share of the country’s GDP, a total of $49 billion (US). For 2018, Japan ranked ninth among the top global tourism earners, and came in second in percentage change of earnings, at 19 percent growth, beaten out only by first ranked China.4 Tourism in Japan is big business. The World Heritage listings of Japan, now numbering a collection of 23 (many of these are multiple sites),5 have been a core part of this business. Think Mount Fuji, the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Dome, Himeji Castle, the temples of Kyoto and Nara – all are part of the World Heritage listings. The plan is to expand these further, with Kyushu a major target as it is further from Tokyo and Kyoto where a majority of the “Meiji Industrial Revolution” sites are located.

Two narratives: Japan’s patriotic fantasy and the reality of industrial exploitation

The history of industrial revolutions in all countries around the world has involved the introduction of modern technology. But industrial revolutions also require new forms of labor to operate these new technologies. The story of industrial revolutions as only the rise of new machines is a fantasy long dismissed by historians. Industrial revolutions have occurred because those organizing new enterprises have found alternative ways for harnessing the labor of workers in new settings, whether in the mills of Manchester or the mass production lines of Henry Ford or hull construction at the Nagasaki Shipyard.6

But somehow, according to the Japanese government narrative, new machines (what the government narrative simplistically calls “technology”) were introduced into Japan from the West between 1850 and 1900. The Meiji Restoration began in 1868, but the sites push the beginning date back to late Tokugawa, allowing a convenient “half century” for Japan’s “industrial revolution.” Japan developed its own versions of these machines (“technology”) combining Western and Japanese know-how, and by 1910 (just two years before the death of Emperor Meiji and the end of the Meiji Era) the whole process was “established.” This remarkable event is unmatched in history in terms of its precise completion point. Everything after 1910 is then presented as just a continuation of this “development.” This compartmentalized view of history was put forward by Japan in its statement to the World Heritage Committee in 2015, again eliding any mention of how labor contributed to shaping industrial innovation:

“After 1910 … Japanese industrial development continued to grow, relying more and more on imported raw materials, but its concentrated period of technological innovation associated with the blending of western and Japanese technologies had come to an end: the Japanese industrial system was established.”7

The official Japanese government website for “Japan’s Sites of the Meiji Industrial Revolution” describes – in Japanese – Mitsui’s purchase of the mine from the Meiji government in 1889; its development by the company’s president Dan Tokuma; introduction of new technology, including some brought in from England; and abolition of convicts and women working in the mine by 1930. The historical description then leaps from 1930 to 1997 when the mine closed – leaving a gap of 67 years. The English language version of the historical description only gives you the technology information, with Dan Tokuma and scant mention of convict labor.

Omission and failure to consult with all those affected by the site – Australia, the United States, Britain, South Korea, China, the Netherlands, and Southeast Asian countries – is unfortunately the Japanese government’s style for promoting its history through UNESCO and elsewhere, which is the major criticism that will be brought up at the July UNESCO meeting.8 Why weren’t these other countries consulted, given that a number of the World Heritage listed sites used forced and slave labor from these countries at these sites during World War II? The coal mines at Mitsubishi’s Gunkanjima (Hashima) and Mitsui’s Miike are the most egregious disregard for this requirement World Heritage listings oversight.

If you go to the local website for the Miike Coal Mine, promoted by the Omuta local government and different than the national government website, you are greeted with a banner photo of cheerful Japanese miners riding underground to the coal face no doubt taken in the 1950s. The historical chronology of the mine’s history is entirely in Japanese. It notes that in one year during World War II coal production reached a new high. In another year, we learn that the mine was hit by bombing, but no mention is made of the constant incendiary bombings by American planes in 1945. No English is provided on the site, nor is Korean or Chinese, the three main languages of foreign visitors to Japan. It is at the local level that the historical documentation is the most distorted, and designed almost entirely for Japanese tourists.

Were all Miike coal miners Japanese from 1939 to 1945? The Omuta website would lead you to this conclusion. Here is the reality for those years – World War II.

Mitsui Miike Coal Mine Workforce – 1940-1945:

- Total workforce (all employees) by early 1945: 15,160

- Japanese (all employees): 11,000 / probably less than 10,000 miners

- Total non-Japanese: 4,160

- Korean (all employees): 1,683 (50 deaths)

- Chinese (all forced laborers): 564 (47 deaths)

- Allied POWs: 1,913 (139 deaths)

- American POWs: 829 (59 deaths)

- Australian POWs: 440 (20 deaths)

- British POWs: 268 (18 deaths)

- Dutch POWs: 355 (41 deaths)

- Other Nationality POWs: 21 (1 death)

Death rates in this group would confirm the abusive treatment and extreme death rates of these non-Japanese workers consistent with slave labor.9

Japanese listed in the table above include all employees (surface, underground supervisors, guards, and actual miners), averaged over the seven year period. Women are not included in the sources for these statistics, but there is no evidence of their presence underground during the war, in contrast to smaller mines to the north in Kyushu’s Chikuhō region. Koreans include all employees, the vast majority forced laborers, in addition to a small number of guards serving as collaborators for the Japanese. Chinese were all forced laborers, the majority most likely farmers taken by force in China, while a minority were prisoners-of-war who had been fighting against Japanese troops in Northern China. Allied prisoners-of-war arrived at different times, with Americans, Dutch, and British arriving earlier. Australians arrived later, suffering more than these earlier arrivals from their previous POW camp locations – the vast majority coming from the Thai-Burma “death” railway construction. The estimated total forced labor numbers, with some deduction for Korean guards, was probably over 4,000. For Japanese underground supervisors, there generally was one for each group of five to six miners, reducing Japanese employees from 11,000 to about 10,200, and then below 10,000 for guards, and reduced even further if administrators are subtracted. Many POWs worked in the Mitsui foundry adjacent to the mine, but foundry employment numbers were small compared to the mine. A handful worked on the surface in various service capacities. With these other POW positions taken into account, probably a third of Miike miners of all nationalities were forced – or more accurately, slave – laborers.

This system of prisoners used as workers became widespread in the first decades of the Meiji Era, introduced in Miike in 1873 when the coal mine was bought from local owners by the new Meiji government. When Mitsui took over the Miike mine from the government in 1889, the company continued using convict labor through contracts with the government.10

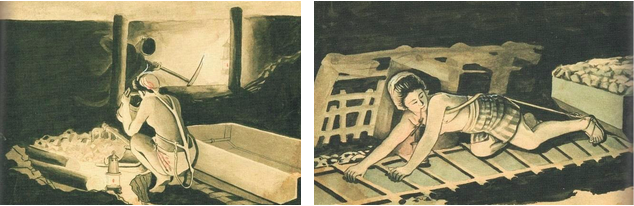

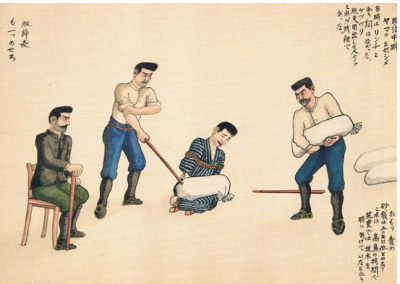

The exact type of punishment used against some Allied POWs in World War II at the Miike Mine was introduced during Meiji, as this painting from the Tagawa Coal Museum in the Chikuhō region of northern Kyushu illustrates. This particular disciplinary practice used on coal miners was known as yama no miseshime – using the mountain to warn others – by forcing the worker to kneel on wooden slats and then placing heavy weight on his thighs, increased as time went by to make the pain worse, along with beatings.11

Painting by Yamamoto Sakubei, Yamamoto Sakubei to tankō no kiroku, p. 26.

Japan’s industrial revolution: The alternative history of energy technology’s introduction

A fundamental rationale for the World Heritage listing of “Japan’s Sites of the Meiji Industrial Revolution” is the central role of heavy industry in this process, focusing on three key industries: iron and steel; shipbuilding; and coal mining. The scope of the industrial revolution, the Japanese government claims, covered the years from 1850 to 1910, spanning the end of Tokugawa and all of Meiji except the last two years.12 The endpoint of this periodization for historians is simplistic when applied to steel (Yahata works) and shipbuilding (Nagasaki shipyard), but does have some evidence for support. Coal mining, however, is not a valid example if underground mining technology is a factor. The way to understand “industrialization” is in how production processes occur, which involves the transition from exclusively manual labor to mechanized labor incorporating new machines and technology. Mitsui’s Miike Coal Mine is generally considered to have been the first “advanced” coal mining operation in Japan, but underground its operations remained primitive until the early 1920s when minimal mechanization was introduced in some mine pits. This is a decade after the “1910” designation. Japan generally lagged behind Western technological advancements in underground mining until after World War II. The way to track this lag is through the history of changes in Mitsui’s workforce from the 1890s through 1945 and how its changing workforce was utilized.

Coal fueled industrialization in modern Japan. Japan’s coal fields contained bituminous coal, but not anthracite, the type used for coke in the production of steel. Japan’s coal was used entirely for energy. Meiji certainly was an era when the origin of Japan’s industrial revolution occurred in terms of large scale extraction of coal and introduction of surface mechanization (hoists, water pumps) that allowed expansion of coal mines. Rail expansion used coal for engines. Modern manufacturing required new sources of energy, and these were either from hydro-electric or coal-fired plants. Electrification of Japan’s cities drew from these plants, but especially utilizing coal as the source.13

Important developments in coal mining centered on the rise of the two most important private business combines in late nineteenth century Japan: Mitsubishi and Mitsui. By the 1880s, these two zaibatsucontrolled the two largest coal mines in the country, both based in Kyushu: Takashima (two islands, one being Gunkanjima on Hashima) off the Nagasaki coast, bought by Mitsubishi from the Meiji government; and Miike Coal Mine at Omuta (Fukuoka prefecture, bordering Kumamoto prefecture), bought by Mitsui. During this period, the largest coal fields being developed in Japan were in Kyushu (Takashima’s islands, Miike at Omuta, and the Chikuhō region in northern inland Kyushu between Kitakyushu and Fukuoka city). Large scale development of the huge Hokkaido coal reserves occurred later and did not rest on major technological innovations of the industry between the 1880s and 1920s.

Mitsui relied substantially on contracting convict laborers from the Meiji government from the 1880s until 1900 at the Miike Coal Mine. Following the 1899 Prison Law restricting convict use, a national cap of 400 on the number of convicts allowed in coal mining shifted the Miike workforce from predominantly convict to a rise in husband-wife teams, known as sakiyama / atoyama (hewer / helper), drawn from farming areas around Omuta, with men extracting the ore and women collecting it hauling it to the surface.14 Chikuhō mines, even those of Mitsubishi and Mitsui, had less capitalization and came to rely on cheaper

Inoue Tamejiro, artist. Portraying women miners in the Miike Coal Mine, “Meiji jidai no tankō fūzoku” [Meiji Era coal mine customs], in Sakubei, pp. 59, 60. This system may have increased during the 1900s with the reduction of convicts used in both hewing and gathering coal.

Korean labor brought in after Japan’s colonization of Korea in 1910. Productivity above ground may have driven this dynamic as well, with Mitsui’s Miike Coal Mine efficiency due to shorter transport links between mine pits and harbor at Omuta, compared to Chikuhō mines further inland that had to send coal by rail to ports at a considerable distance to the north. Dan Tokuma became head of the Miike Coal Mine in the 1890s and introduced a number of administrative reforms at the turn of the century. The shift away from convict labor also involved an end to using contractors for non-convict Japanese miners, with the aim of eliminating turnover while seeking to gain local loyalty of workers, what historian Tanaka Naoki has described as “a familial approach to business management.”15

The following table documents the radical shift from convict to non-convict labor at Miike from 1894 to 1900, and then the sharp rise in women workers afterward, finally ending after 1930 when all women were excluded from underground work at Miike.

Hoists and air shafts were introduced during late Meiji (1890s to 1900s), but more advanced mining technologies for underground mining only arrived in the following decades – after Meiji. These were technologies developed first in the West, but only introduced later in Japan. According to Donald Smith, “Mitsubishi and other major mines began another spurt of mechanization in the latter half of the 1920s, building on the changes in mining practice in the early 1920s.” This shift was from sole use of mining tunnels – the room and pillar system, zanchūshiki saitan – to long wall extraction, chōhekishiki saitan, combined with room-and-pillar. “Mines installed boring machines and rock drills, eliminating the necessity of drilling holes by hand for dynamite. From 1927 or 1928, they installed coal cutters [undercutters essential for long wall mining] … mechanical picks [and] face conveyors, which sped the coal on the first stage of its journey out of the mine.”16 This technological transformation in the 1920s resulted from Mitsubishi’s and Mitsui’s ready access to capital through their zaibatsu internal banks and other divisions, resources not available on the same scale for smaller companies.17

Photos from 1926 Mitsui Miike yearbook, in Sakubei, p. 74. Examples of continuing primitive conditions underground at Miike in the 1920s. The loin cloth miner’s dress is exactly the same attire that Allied POWs wore in the mine during World War II, what Australian POWs described as a “G string.”

Specific mechanization developments crucial to modern coal mining were only introduced into Japan in the 1920s at the most advanced mines, including Miike Coal Mine. By contrast, many mining equipment innovations outside Japan occurred in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but were not introduced into Japan until the change to longwall mining. Priscilla Long provides one of the best descriptions of the longwall system:

“Longwall mining can easily be understood if one thinks of a bed of coal as an underground field extending for hundreds or thousands of acres. When coal is reached by shaft or slope, a main entry is driven. … Then two parallel tunnels are driven off to one side, four hundred to six hundred feet apart. … Between the tunnels, made permanent with timber and other construction material, the longwall mining is done. The miners (a whole gang rather than just two or three in a work space) work at the face under a set of movable pillars, which they move forward (one at a time) as the face recedes.”18

American coal miners resisted the longwall system until the 1920s because skilled miners viewed it as eroding their control over the work process they had with the room-and-pillar system. Implementation of the longwall system changed the work environment from one that was more artisan-based to one similar to a factory environment, with teams and direct supervision, and new machinery required to extract and load coal. The Japanese coal mines also had individual “artisan” miners, but they were the dual system of husband-and-wife miners in contrast to the American all-male underground setting. American miners in some locales had a strong union movement by the early part of the twentieth century that led to resistance to mechanization, whereas Japanese miners had no substantial labor organization until World War I. The change to teams and longwall mining appear to have been driven by Mitsui’s management introduction of new technology among miners. Japan’s first labor union, the general membership Yuaikai, had a coal mining membership base, and in 1912 Mitsui coal miners went on strike for five months, Japan’s largest prior to World War I, but were defeated by the company.19 Trade union organization among coal miners revived under a different industrial union formation during the 1920s, but could not be sustained under the impact of the Great Depression by the 1930s.20 In contrast, the United Mine Workers of America became the backbone of the industrial union organizing movement in the United States by the 1930s with a membership of over 800,000 by the early 1930s.

The lag in the rate of mechanization in Japan’s coal mining related to over-reliance on labor intensive production, a dynamic that did not substantially change underground until the 1920s. Below are examples of coal mining equipment innovations internationally. These were not introduced into Japan, including the Miike mine, the country’s most advanced, until after the end of the Meiji Era.

Innovations in coal mining – international introduction:

- Coal cutter – 1876 in U.S. (Lechner)

- Punch / pick machine – 1877 in U.S. (J.W. Harrison patent)

- Rock drilling tools – 1882 in U.S. (Brunner and Lay)

- Mechanical drive systems – 1883 in Switzerland (ABB)

- Undercutting chain machine – 1913 in U.S. (Sullivan Machinery Co.)

- Loaders, continuous miners – 1919 in U.S. (Joy Mining)

- Excavators, haulage trucks – 1917 in Japan (Komatsu)

- Mining & loading machines – 1925 in U.S. (McKinley; Jeffrey-Morgan)

- Pit car loader – 1925 in U.S. (Hamilton)

- Coal loading shovel – 1925 in U.S. (Jones Coloder, others)

- Scraper loaders – 1925 in U.S. (Goodman)

Japan did introduce some innovations, as the Komatsu example indicates, but this was after Meiji, and this innovation did not change the crude underground system of industrial relations heavily reliant on manual labor. Coal loaders, marketed by 1918 by a number of American companies, appear to have been absent at Miike, which was still using horses in the 1920s for pulling coal cars along tracks where they could then be brought to the surface.21

Limited mechanization took off in the large mines in Japan after the First World War, driven by major shifts in the labor structure within mines. Takeshima (Hashima / Gunkanjima) and Miike mines led the way, leading to increased miners’ wages while maintaining relatively primitive labor practices underground. Mechanization in the 1920s at Miike coincided with introduction of longwall mining and teams to remove coal, which reduced the use of women to collect the ore. Mine work now utilized teams that loaded huge volumes of coal that could be shoveled into coal cars and then hauled to the surface via lifts. Smith states that this process was possible once coal cutters were installed with face conveyors, but this change appears to have been confined to major mines in Chikuhō and not all the pits in Miike.22

By 1930, the Miike Coal Mine in Omuta completely eliminated both convict labor and women workers underground. The company claimed that removal of females from underground work was in line with Japan’s agreeing to the ILO stand of 1928 for the elimination of women from underground coal mines, but Smith believes that the company’s decision was a consequence of technological change. Women continued as surface workers sorting coal. The practice of using women miners underground continued informally in smaller mines of the Chikuhō region, despite the national government prohibiting the practice by 1933. Japanese women returned to underground work at the end of World War II, but there is no indication they did so at the Miike Coal Mine.

Histories of Japanese coal mining on women published in English have tended to focus on the Chikuhō region of northern Kyushu, where there was a wide diversity of small, medium-sized, as well as some large mines operated by Mitsui and Mitsubishi. In that region women continued to work illegally in the medium and smaller mines after 1930. These are significant studies, but only reveal part of the larger picture of Japan’s coal mining history, particularly during the Pacific War.23 The Miike mine was located in an entirely different coal field, where Mitsui employed quite different labor practices. Distinctions in regional coal fields of Japan are crucial to understanding the contrasts between mines where women miners were employed and those where they were eventually pushed out of underground mining after 1930. The map below, from Arents and Tsuneishi (p. 126), shows the distinct geography of these separate regions that was an aspect of these two quite different coal mining environments.

Japan’s wartime empire and slave labor at the Miike Coal Mine

The history of Japan’s “Meiji Industrial Revolution” World Heritage sites is directly linked to Japan’s war and pursuit of empire in the Asia Pacific. During the Meiji Era (1868 to 1912) Japan colonized Taiwan, the Ryukyus (Okinawa), and Korea, and gained footholds in Manchuria and ports in China. This expansion of empire required a modern navy and army, with steel, ships, munitions, and coal as the economic foundation for Japan’s competition with the West. Mitsui advanced into East Asia after the first Sino-Japanese War, initially establishing operations in Taiwan, Korea, Manchuria and China from 1896 to 1907.24By the advent of the Pacific War in the 1930s, Mitsui was the largest Japanese company to invest in China and Japan as supplier of military and civilian imports.25 With Mitsubishi, Mitsui laid the foundation for Japan’s economic and military dominance of East Asia and the western Pacific.

In 1938, with Japan’s massive escalation of its invasion of North China, tonnage of coal extracted from the Miike Mine accelerated, peaking by 1944 at over 4 million tons. But in 1945 production collapsed along with the rest of Japan’s productive capacity and infrastructure, and its empire, the euphemistically dubbed “East Asian Co-prosperity Sphere,” vanished. This term is nowhere to be seen in historical presentations – in English – at the World Heritage sites where “history” has become clean, technological, and a patriotic celebration of national achievement.

Japan’s model of war production was exemplified by Mitsubishi’s Nagasaki Shipyard, the largest shipbuilding complex in East Asia during the Second World War. During the Pacific War (1937 to 1945) the Nagasaki Shipyard built 72 warships and 15,000 torpedoes. Mitsubishi turned the entire metropolitan region around Nagasaki city into a military-industrial complex with over 24 industrial and technical facilities, using thousands of Korean forced laborers and Allied POWs as slave laborers, including Australian POWs who produced materials for the Nagasaki Shipyard at Mitsubishi’s nearby foundry in the Urakami District.26 Mitsui had returned to its labor system using prisoners, but a new type that combined waged Japanese workers with foreign slave labor that had its origins during the early years of Meiji of convicts.

POWs at Fukuoka 17 – Japan’s system of slave labor from Burma to Omuta27

The Australian POW experience is particularly important for understanding how the major zaibatsu, particularly Mitsubishi and Mitsui, were instrumental to Japan’s war production and brutal occupation of East and Southeast Asia. Mitsubishi supplied the merchant ships, known by POWs as “hell ships”, that transported POWs from camps on the Thai-Burma railway construction (known as “The Line”), via Singapore, to Japan. Mitsubishi also supplied cross ties for the Thai-Burma rail construction.28 Australian POWs on “The Line” – in terms of percentage of the Australian population – far outnumbered the British, even though more British soldiers were POWs there.29 By 1945, the Australians outnumbered the British at Fukuoka 17 POW camp in Omuta, working in the Miike Coal Mine. Most POWs underground at Miike were Australians and Americans. The Australians also appear to have led the resistance inside the mine.

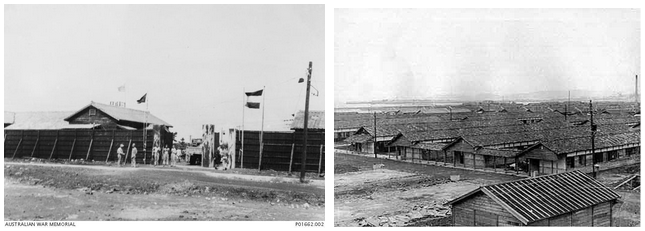

Mitsui’s Miike Coal Mine was a larger complex spreading across Omuta, with a rail, foundry, and port built by Mitsui. When Australian Private Roy Whitecross arrived at Moji port in northern Kyushu prior to the journey to Omuta, after years in Changi prison and on the Thai-Burma Railway construction with others from the AIF 8th Division30, he wondered if conditions would be better as a prisoner-of-war in Japan. But encountered conditions more deadly than Changi and in many respects on a par with the “Railroad of Death” in Burma. He learned from the other Australian POWs, at Fukuoka 17 for a year, that they’d work ‘like slaves’ in Mitsui’s coal mine.31

AIF Private David Runge found the “huts” at Fukuoka 17 far better than what he and thousands of others had experienced while working on the Thai-Burma Railway. Each POW had their own “mat” (tatami), blanket, … straw pillow. Overall he found the dorm room clean. The tatami were a perfect accommodation for lice, of course, but compared to the torrid tropics the sleeping quarters were “very good.” But there was no heat, and winter snow at Omuta could reach over a foot, making the cold a serious health hazard. The problem with the non-work environment centered on two issues: first, the food, which was meager and at times inedible; and second, the constant harassment, regimentation, and beatings by Japanese guards.

Photos: Australian War Memorial: Entrance (post-surrender) to Fukuoka 17 POW Camp, Omuta, next to Mitsui Miike Coal Mine. Photo on right: Center for Research – Allied POWs under the Japanese, website: overview of POW barracks.

AAMC32 Captain Ian Duncan was one of the camp doctors. Like Runge and hundreds of other Australians at Fukuoka 17, he had been stationed along the Thai-Burma Rail construction. He had been beaten almost daily by Japanese guards while serving on “The Line” because he was the one who had to tell the Japanese who was too sick to go to work. He got the blame, as they assumed he was lying, thinking that only visible injuries qualified for time off. Malaria. beriberi, and dysentery didn’t count. Conditions for medical staff were considerably better at Fukuoka 17, including better hospital facilities, but medical supplies were virtually non-existent. Health conditions were equally horrendous for those working in the mines. Malnutrition was so bad that men talked only about food, and they showed no interest in the Japanese women digging gun emplacements near the camp working with no tops during the hot summer.

The Red Cross sent food supplies to the camp, but these were secretly stockpiled by the Japanese and not distributed to POWs. They were discovered only after the surrender in August 1945. Runge describes what rations were like at the camp mess hall:

“The rations consisted of a bowl of rice…like a small pudding dole, very small, and … a couple of these pickles, like cucumbers … or seaweed. That was to take down the mine. But we used to eat it before we went down the mine. … Back in camp they’d have dog soup. I never ate dogs. … Back in camp, everybody traded. … You’d get somebody didn’t feel too well and they’d sing out ‘I’ve got rice for rice and soup on Wednesday night.’ And somebody who’s hungry’d sing out, ‘I’ll give you rice and soup on Wednesday night for that rice now.’”

It was like a market, and those who traded but didn’t come through with their promised rations would pile up “debts,” eventually declared “bankrupt” by the other men, losing all their rations each day. A Dutch “padre” (chaplain) helped the “bankrupts” by providing them with minimal rations so they wouldn’t starve.

The “cook house” (as Runge called it) was run by U.S. Navy Lieutenant Commander Edward Little, a man who routinely harassed POWs for what he considered poor behavior. The Japanese camp heads put Little in charge, and as a result he received special privileges, including withholding Red Cross food supplies from the POWs that he accessed himself. He was detested by the Americans and Australians, and after the war was court martialed for having reported U.S. Marine Corps Corporal James G. Pavlakos to the Japanese authorities for selling a bowl of rice to James O. Wise in exchange for two packs of cigarettes. Pavlakos was punished and beaten for nearly 30 days by the Japanese until he died. Three other American POWs died under similar circumstances – Little reporting them for small “infractions,” followed by beatings and death.33

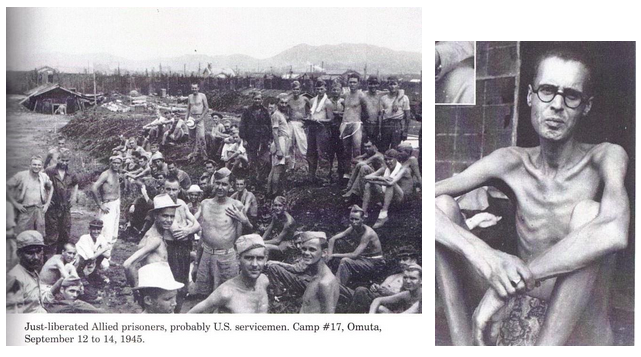

Photos by George Weller, from George Weller, ed. by Anthony Weller, First into Nagasaki: The Censored Eyewitness Dispatches on Post-Atomic Japan and Its Prisoners of War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2006)

The Miike Mine had eight levels and ran two miles under the sea from entrances at Omuta. Fukuoka 17 was actually built on land fill from mine slag. Temperatures underground ranged from freezing at upper levels to virtually boiling at the lowest level. The miners often had to work with their legs submerged in water. Runge described how they routinely put on their “G string” before descending down the shafts. This practice of wearing only a loin cloth went back to the early years of Meiji when the mine first opened and continued through the 1920s and 1930s. Miners’ clothing of this type reveals how inadequate the ventilation systems were at Miike, even during World War II. But the tunnels where the POWs worked were often ones Mitsui had abandoned in previous decades, with timber pillars rotting and cave-ins frequent. American journalist George Weller, the first non-Japanese outsider to reach Fukuoka 17, on September 10, 1945, learned that “[b]oth those Mitsui mines worked by Americans and those worked by Chinese are defective, ‘stripped’ mines, dangerous to operate because their tunnels’ underpinnings have been removed to obtain the last vestiges of coal.”34 David Runge and the other Australian POWs were also working in those mines.

Men worked in tunnels but also in longer underground stretches – the long wall mining that began in the 1920s when technology made this possible. Miners dug out the coal, usually with hand picks after dynamiting a section, and other times with pneumatic jackhammers. Roy Whitecross recalled “twenty American prisoners … working a ‘long wall’ [with] the roar of machinery and the clank of the scraper chain [making] speech all but impossible.”35 This was the undercutting machinery brought into the mine during the 1920s, one of the best indicators of “modernization” for any coal mine. The coal was then loaded into coal cars (skips), and winding gear pulled the cars up to areas where the coal could then be loaded onto hoists that would take it to the surface. The winding gear cables would sway back and forth across the low, narrow tunnels, forcing men to negotiate past the skips and tracks for the coal cars and tracking. Dr. Ian Duncan found that many injuries were caused by these cables hitting limbs of the miners walking through these tunnels.

David Runge’s interview of 1983 reveals the POWs confusion about how the shift system operated. American POW Stanley Kyler, from Dekalb, Illinois, told George Weller, “I’ve been working twenty-two months for Baron Mitsui. Four months was driving hard rock, and eighteen months was shoveling coal, twelve to fourteen hours a day.”36 Runge recalled that the POWs worked 12 hour shifts, but that these constantly rotated, giving the men just enough time to eat and then sleep. Whitecross explained how the rotating three shifts system operated:

“The first shift left camp at 4 a.m. and returned at four o’clock in the afternoon. The second left camp at noon and returned at midnight, while the third, or night shift, went out at 8 p.m. and returned at 8 a.m. the following day. In addition to these shifts, a permanent day shift carried out maintenance work at the mine. Apart from a small number of men who worked in welding shops and other engineering plants, all shifts worked below ground in two sections, one working the actual coal and the other carrying out work incidental to the coal hewing, such as drilling tunnels, laying railway lines, shifting rock, and a dozen-and-one miscellaneous tasks.”37

The POWs had no free time, using every spare minute to try to sleep before returning to the mine, often on a different shift. It appears that the work week based on constant rotating shifts – with no time off except every month or so – amounted to approximately 80 or so hours. Ian Duncan said that the men working in the mine had to walk about a mile from the POW camp to the mine entrance for each shift, adding to the workday. The exhaustion resulting was so severe that some men deliberately had other POWs break their foot, leg, or arm so that they no longer had to return to the mine depths.

A zinc foundry was connected to the Miike complex. According to former Australian POW Tom Uren, he and the other POWs took a tram to the foundry, something the POW miners could not do on their trek to the mine pit. Working conditions at the foundry were far better than down in the mine, with Dutch POWs the main group.38 The better jobs generally were held by POWs who had arrived earlier, particularly the Dutch. British POWs apparently were concentrated at the port loading coal onto ships. Uren got a foundry job most likely because he arrived only months before the end of the war, having earlier worked at the copper smelting works of Nippon Steel Works (which owned Yahata Steel Works in Kokura, another “Meiji Industrial Revolution” World Heritage site). He too had previously been a slave laborer on the Thai-Burma Railway, like his other Australian compatriots at Omuta.

There seem to have been few deliberate executions at Fukuoka 17 (such as beheadings or bayonetting), in contrast to POW camps outside Japan, especially in the Pacific islands and Southeast Asia. Deaths occurred from a combination of constant and severe beatings by guards and supervisors, disease from the terrible conditions and freezing weather in winter, and malnutrition that prevented recovery from disease and beating injuries. Infections were common, with medical supplies lacking. The Red Cross supplied surgical instruments, sulfur drugs, aspirin tablets, plaster of paris, and other medical equipment and medications, but the Japanese prevented access to these, confining them to their secret storehouses. Dr. Duncan believed that had these supplies been released, many lives could have been saved.

AIF Private David Runge’s story – from rural Murwillumbah to warzone Omuta

Too often the POWs’ experiences in Japan have been treated only as those of “victims.” But the Chinese forced labor response to Japanese authority in the Hanaoka Coal Mine uprising, escape, and subsequent massacre by the Japanese in Akita prefecture, northern Honshu, indicates a broader pattern of resistance to Imperial fascism within Japan, focused particularly in the coal mines run by Japanese companies.39Australian Private David Runge’s account as a POW at the Mitsui Miike Coal Mine opens a new perspective on this resistance.

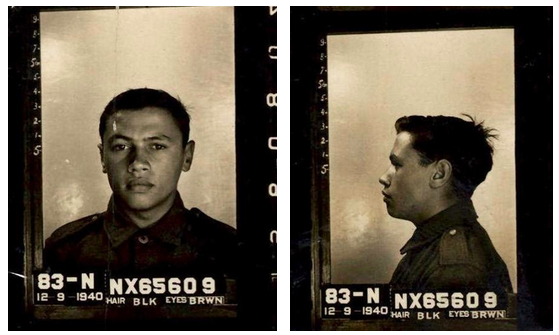

His background growing up in rural, agricultural Australia helped prepared him for the ordeals as a prisoner-of-war. He was born in 1922 in Murwillumbah, New South Wales, a small town near the Queensland border ten kilometers from the Pacific Ocean coast. He grew up in the town’s Solomon Row community, with its mix of South Sea Islander, Aboriginal, and South Asian residents of color. His father, Albert Ernest David Runge, was born in Denmark in 1898. After coming to Australia, Albert married Florence Silva, who was born in Queensland a year before her husband. Florence’s’ father, David Silva, was born in Ceylon in 1846, and arrived in Australia in 1881, before the “White Australia Policy” excluded Asian migrants from entering the country. The ancestry of Florence’s mother, Emma, is not known. These details reveal the multicultural character of David Runge’s family heritage. His mother died in 1931 when he was only eight, and his father seems to have vanished from his life at that point, leaving him in the care of his older sister May, who he listed as next-of-kin when he enlisted in the Australian Army in 1940 as “Dave Runge.”40

He went to work after finishing primary school, and as a teenager became a driver at a local banana plantation. South Sea Islanders were a regular part of the agricultural workforce in the banana and pineapple plantations of northern New South Wales and Queensland. In his 1983 interview, Runge told of how he enjoyed growing up in this community and how he identified as Australian. He never made any mention of race or color in talking about his Australian upbringing, even though discrimination against anyone of color during those years would have been comparable in many ways to racial segregation in the United States, but not the extremes of the South. After he entered the Army, lying about his age as he only was 17, he seems to have found a new family and community, feeling a strong connection to his “mates” and a sense of responsibility as a soldier. Above all, his story from childhood to the many experiences as a POW in Southeast Asia and then Japan, is one of survival and relying on those few he felt he could trust.

Photos: “Attestation” (enlistment) papers for David Runge, National Archives of Australia

David Runge’s view of the Japanese, in terms of their racism toward other Asians, was a revelation when he became a POW in Singapore, where he was put in Changi Prison. It was a world apart from his roots in the multiracial Solomons Row community of Murwillumbah.

“I always thought Japanese were like us, when we fought ‘em. … Like their attitude – Japanese soldier and us. But I seen enough in Singapore when they cut off people’s heads, and I seen a bunch of five or six Chinese women with their lips sowed up and dragged along the street by string, and these sorts of tortures that went on around the place. Well, you get a different attitude toward the Japanese then, don’t you. The Asians thought that when the Japanese came down that [the Japanese were] ‘Asia for Asians.’ But it was ‘Japanese for Japanese.’ The Asians that spat at us and threw stones at us when we got taken prisoner, in the end they become to realize where their bread and butter was buttered, they kept waving flags secretly and putting up their thumbs in the ‘Hello Joe’ sign. Then they realized that the Japanese weren’t ‘Asians for Asians.’”

Photos from National Archives of Australia: David Runge’s Fukuoka Camp 17 POW card – reverse side lists previous POW camp on Thai-Burma railway construction and arrival in Japan by sea.

By the time he reached Fukuoka 17, Omuta, and the Mitsui Miike Coal Mine on June 18, 1944 he was determined to continue the fight. “My attitude was to do everything in my power to cripple that coal mine.” He acted on his own to sabotage production. “I took emery dust down the coal mine and put [it] in the motors and chewed up the chain conveyor motors … when we was working in the laterals [and] digging.”

He also had a small group around him that worked secretly with other POWs who were American.

“My particular group was to look for coal, and when we found the coal we’d drill a long tunnel through the seam of coal and then the coal extractors would come and take all that seam out and that’s what they call a long wall, in Australia. The jackhammer used to weigh about 60 pounds, and the length of those drills is 13 feet. The Jap ‘Mito Man’ [foreman with a nickname for “dynamite man” because he used so much of it] that was in charge of us, he’d be drilling in like that and since he went in the depth he wanted in the face where we’re drillin’ – instead of us saying with his hands ‘ok, move back’ he’d grab hold of the drill and pull it back, and we’d go falling back over rocks and everything. He’d grab hold of it and pull it forward again, and we’d go slamming, trippin’ over everything again. So what I used to do, and what others did, was put a pick in the ceiling and pull the ceiling down on him, and bung him off, and then tell the ‘buntai jo’ – that’s the Japanese foreman – that the ceiling came down on him, which was ‘tenja cabina’ – the word for cave-in, and we’d beat the Jap out.”

Runge continued the sabotage in other ways when he managed to stay on the surface for a short time.

“One time I put on a crook [injured] back, back in camp. They put us to work topside in the mine workshops. My job was to sharpen the diamond drills. You had to put them in water or something like that to harden them, which I didn’t do. And of course they’d go down the coal mine and in five seconds they be turned to butter. At times I find I’d be repairing the motors I’d put emery dust in.”

Secrecy was essential to conduct this sabotage, because the two main American officers the Japanese had put in charge of the camp, Little and Bennett, were known to collaborate with the Japanese. Some POWs also tried to gain favor with the authorities and could not be trusted. Runge did not even tell his closest Australian mates, including Roy Whitecross, and the man whose mat was next to his, John Towers.

“Down the coal mine I had a very bad name with the Japanese because whenever I worked in a group, say there’s five or six, my number in Japanese was ‘go-haku-go-jyu’, that’s five-fifty [550], and [they] used to say ‘go-haku-go-jyu dunny door’, that’s ‘no good.’ Because every time I went to work something happened to them, or something went wrong. Me and a couple of Americans who were in on this sort of thing, of sabotaging the coal mine, we done it secretly because we didn’t want to reveal what we were doing, because there were people that were lovey dovey with the Japs and you didn’t know if they’d turn you in or not.”

Runge felt that Americans had the most in common with Australians among the POWs. For him it came from an innate sense of connection based on common experience, what he called “race” but actually was about class. “Generally, apart from them two [US officers Bennett and Little, viewed as collaborators with the Japanese], the Americans were … the same as Australians. Like the Japanese would call it ‘onaji,’ means ‘the same.’”

He felt the Australians were very different from the English. “The Australians and English don’t get along anyhow, anytime.” His view may have been influenced by the relative absence of English and Scots in the mines, a group based mainly in the foundry, along with the Dutch. These were the better jobs. But the major differences seem to have been cultural. “Like our humor is entirely different to English, Dutch, German, Russian, Chinese, Japanese, anything. Our way of life, our humor is entirely different. … But the Americans and the Australians, the humor – as the Jap would say – ‘onaji,’ the same. That sort of attitude with one another, we could sling off at one another and it was a joke.” Some of this related back to growing up poor and getting by in the years before the war. “Australians and Americans, at that particular time come from pioneering families. Like the Depression, everybody came out of that Depression. A lot of people can remember that we had corned beef and damper41 and … syrup on the table back home. And so did the American boys. They called their damper ‘corn bread’ or something like that. We were so alike in their upbringing. So therefore we got on well together.”

The Allied POWs were kept separate from the Korean and Chinese forced laborers. The Chinese were treated the worst of any group and experienced the highest death rates. But in the mine this separation could not always be enforced. Roy Whitecross recalled a chance encounter, clearly against company rules, with a Korean miner. Korean forced laborers and Allied POWs would be severely punished if caught fraternizing.42

“One night I was sent to the main tunnel to collect dargo, long, sausage-like pieces of hard clay used for tamping the dynamite in the holes drilled in the rock or coal face. At the truck of dargo I found a Korean on a similar errand. He looked carefully at me, then up and down the tunnel. It was deserted.

‘Goshu, Korea,’ he said. ‘Onaji.’

Apparently he had not been long in Japan either. His Japanese was halting and slow, and I understood him. I indicated that I did not understand his remark that Australians and Koreans were the same.

He answered: ‘All prisoners. Work all the time.’

Keeping a furtive look out for any approaching miners, he unburdened his heavy heart. ‘Nippon, no good. Very little food. Korea, plenty food. Australia?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Australia plenty, plenty food.’ …

He shook his head dolefully, and reaffirmed his belief that Nippon was definitely ‘no good.’ In the distance along the main tunnel a miner’s lamp appeared. Hastily assuring me that Koreans and Australians were the same and that they were ‘friends’ he grabbed his sack of dargo and hurried into the inky blackness of hatchiroash tunnel.”43

One act of sabotage Runge and his group carried out involved a character they called “Pinto Rice.” From his 1983 interview it is probable that ‘Pinto’ was Japanese. ‘Pinto Rice’ could have been a play on ‘Binto box’, Runge’s way of saying bento box, used by the Japanese for the POWs’ rice ration. Or it could simply have been taken from ‘pint-a-rice’, the standard small ration, and perhaps this man was small in stature and Asian in appearance. Runge’s Japanese foreman this one day told him that if his group loaded extra skips full of coal that they could have a shushin – quick nap. Runge’s team followed through, but then the foreman refused and wanted more skips loaded. Runge got into an argument with him, to no avail. His team then loaded more extra skips, but the system of moving the coal cars along the track incline required stopping at a certain point.

“[This Japanese foreman] used to stand on the front of these full cars. And as he went down that tunnel, and as he went past – there’s a button on the wall – he’d hit that and … the red light’d flash up where this ‘Pinto Rice’ [worker] was at the top, and [Pinto would] put on the brake and stop it. The [foreman] would connect the other full cars and they’d pull them up into the main line. So [the foreman] would ride in the front. And as they went down the cable … he’d hit that, the red light’d go on and Pinto would put on the brake.

“When [the foreman] went away [after the argument], I raced up to this ‘Pinto Rice’, and I said, ‘Now when he goes down with those two full cars and he hits that button, don’t stop it. Because he’d be ridin’ in the front, see.’ So Pinto said ‘ok.’ So when he come and he hooked on these two full cars, took ‘em out and changed the points, and then he had to go down the slope, down underneath. We seen the red light glow through the tunnel when he hit the thing. Pinto didn’t stop it, and that drove him clear into the coal face.

“We had to go down there, and … we dug him out of the coal, and he’s still alive. His pelvis and everything was crushed. So we dug him out, and the Jap [Pinto – as the foreman was unable to talk after his injury] told us to take him up topside. So he [presumably Pinto] said, look, we got to kill this bugger before we get him up topside, otherwise he’s going to squeal, you know. He’s going to tell. So we threw him [the foreman] over tops of coal trucks, down there. Fell down on the other side. Dropped him. We done everything. He wouldn’t just die.”

Another foreman ranked higher than the injured man arrived and organized the men to take him up to the surface and then to the hospital. Runge and the POWs feared that the injured foreman would tell what actually happened, that the accident was deliberate. But the foreman was unable to speak and eventually died, saving Runge and the POW rebels – and Pinto – from brutal punishment.

David Runge’s ordeal – torture and survival

On February 12, 1945 Runge’s luck ran out. The Japanese in charge that day made him a leader of a team of Australian POWs who had just arrived at the camp. They were inexperienced compared to Runge and the others who had been there a year, and they were the type of POWs Runge did not trust, men he differentiated as “new” versus his “old” crowd that he felt he could rely on. To help these new Australian POWs, he told them not to work too hard. But there had been coal car derailments that day, making the Japanese foremen angry. Runge and his team had been clearing rocks rather than loading coal, and the foreman was dissatisfied with their rate of work as well.

Two of the new Australians were pulled aside, and they revealed to the foreman that Runge advised them not to go too fast. But more was involved than just Runge’s go-slow advice, as he had secretly been carrying out a particular form of sabotage.

“There was a couple of Americans and me. … We sabotaged the mine as much as we could sabotage it, and destroy everything that we could destroy, to knock down their production. This particular time I told these guys that was with me – and they were new Australians, I was the senior guy. When we used to load these rock cars, the coal cars, I used to get all the rocks and stand them up perpendicular … so it looked like a full car.

“Anyhow one of these flamin’ coots [actually two, according to Runge’s affidavit for War Crimes trials] went and told the Jap. And of course when we got into topside they called me out. It was snowing, really snowing, and they got me and this American. They hit the American fair across the mouth, and he went down, which I shoulda went down. Because once … the American … went down they let him alone. They got hold of me, they put me up on a box, and tied me thumbs up on a rope, kicked the box from underneath me and wacked me with sticks and god knows what.”

The guards then marched him through deep snow and took him to the prison cell, known as the aeso to the POWs. He was forced to kneel on bamboo slats placed on the cold concrete floor.

“This [guard] used to come and stand on me thighs and squash me legs into the bamboo. If you can realize the bamboo was about four inches in diameter. I had to kneel. There’s one [bamboo piece] forward, and the other [bamboo piece] was near me shin, and I was suspended on that above the ground in the kneeling position. The Sailor [Takeda Sadamu] used to come and stand on me thighs to push that into me shins. I’d be kneeling down and they’d say ‘Stand up!’ And I’d stand up. With the soreness you’d start to get cold again. They’d say ‘Kneel down again!’ And they’d kneel me in again. At night time they’d stick us in the cell, and in the morning they’d come along and kick us in the ribs, get us up again, and straight back onto the bamboos. In the end I couldn’t stand up.”

This torture continued for five days, the first two without food or water, and with only thin clothes in the bitter cold of the prison room. Finally two POW orderlies took Runge to the camp hospital. Dr. Ian Duncan found Runge’s legs were frozen solid. After several days gangrene set in, and Doctors Hewlett and Duncan had to amputate his legs, but could only do it with a common saw. Fortunately Runge was given a spinal injection that made everything from his waist down numb, but he could still hear the saw cutting through his legs.

Even as he recovered from this horrendous torture the drama was not yet over. An American POW, orderly Bill Zumar, took Runge to a separate room in the hospital a few days after the operation. Zumar was from the town of Comanche, Oklahoma, which had been part of the Chickasaw land grant after Indian removal from the Southeast before the Civil War. Whether Zumar was Chickasaw, Cherokee (the largest Oklahoma tribe), or not, he talked to Runge like a Native American who knew when one had to fight to survive.

“He said ‘Dave, do you know why they put you in here?’ None of us ever told lies to one another. No prisoner lies to one another. … [I said] ‘No.’ ‘Because the Japs are going to come in and bandage you … I brought you this piece of iron. Now when the Jap makes a swing at you, goes with the bayonet, knock it aside real quick and hit him over the head, and take his rifle and you might be able to shoot a couple of them before they kill you.’ Well you can imagine you’d be in that situation, you got no legs, you know you really and truly got to sit there and take it. …

“One particular day I could hear these boots coming up this passageway. … They had rifles and fixed bayonets. I thought, well this is it. I took a solid grip on this iron bar behind me back. There was Dr. Hewlett and Dr. Duncan standing there. And I thought to me self, they’re going to bayonet me and these doctors are going to pronounce me dead.

“They had bayonetted an American between the huts. They gave him a cigarette and so they bayonetted him in the back. [That] killing was before we got there. This Japanese captain [Isao Fukuhara] said … to Dr. Duncan and Hewlett, ‘You giving this man extra rations?’ – in Japanese. They said yes. He said, ‘Well you give him food, make him strong.’ They said ok – and they all turned around and went out of the thing, and I was moved back into the ward. That was a hairy experience, I tell you.”

The presence of Duncan and Hewett probably prevented further harm to Runge, as they were witnesses, and they too would have had to be killed to hide Runge’s murder. Captain Fukuhara, who ran the camp, had authorized Runge’s torture. He was tried after the war and executed, along with three other guards who were at Fukuoka 17 and the Miike Coal Mine, including his main torturer, ‘The Sailor’ (Takeda).

Fukuoka 17 was finally liberated in September 1945, over a month after the official surrender. The Nagasaki atomic bombing, visible from Omuta, had made harbor access difficult for the hospital ship needed to accommodate the prisoners-of-war, delaying access to POW camps beyond the city. All the POWs who saw Nagasaki on their return were shocked at the devastation, but no one knew anything about the dangers of radiation at that time. The full impact of the atomic bombing was not understood by any of the POWs, who believed that the destruction of Nagasaki contributed to their liberation. Some at Fukuoka 17 later learned about what atomic warfare meant and the terrible loss of civilian life it caused. Tom Uren, a Fukuoka 17 POW from Australia, was one, and as a result of what he saw firsthand in Nagasaki became an activist for peace later in life, and a leader in the Australian Labor Party as an elected MP and by the mid-1970s the deputy leader of the ALP.

David Runge returned to Australia, and in the following years was fitted with prosthetic legs by Dr. Duncan, who had served with him at the Mitsui Miike Coal Mine POW camp. He moved to Auburn, a suburb of Sydney, and found a new job and a new community. But as Duncan related in 1983, all the Australian POWs he knew from that time, including David Runge, suffered severe stress – what we now know as PTSD. But David Runge, even in 1983, still had a spirit of rebellion and sense of connection to his Army mates from those hard years.

Photo on left from Australia War Memorial: David Runge carried on the back of a sailor on return to Australia, with his best mate John Towers at the front, on crutches from injury resulting from torture at Fukuoka 17. Photo on right: Runge, Sydney Sunday Telegraph, Oct. 14, 1945.

Conclusion – Will Japan tell the full story of the Mitsui Miike Coal Mine?

The Japanese representative at the World Heritage Committee session of July 2015, bidding for international support for World Heritage designation, agreed that “Japan will sincerely respond to the recommendation that the strategy allows ‘an understanding of the full history of each site.’ .. [and] is prepared to take measures that allow an understanding that there were a large number of Koreans and others who were brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions in the 1940s at some sites, and that during World War II, the Government of Japan also implemented its policy of requisition. Japan is prepared to incorporate measures into the interpretive strategy to remember the victims such as the establishment of an information center.”44

At the Omuta Mitsui sites – World Heritage listed – Japan has failed to honor the workers who were prisoners at the Miike Coal Mine, and has failed to consult fully with representatives from South Korea, Australia, the United States, the Netherlands, Great Britain, China and other countries whose people worked at the mine during the war. The Japanese government needs to begin to tell the full history of this mine, consistent with its legal obligations agreed to under the World Heritage Committee’s requirements.

The Japanese government’s omission of this disturbing history from its “Meiji Industrial Revolution” sites is a disservice to the Japanese people and their own history, as it was Japanese convicts, Japanese miners – men and women – who suffered in earlier decades before the forced slave labor of Koreans, Chinese, and Allied POWs. The ‘smiling miners’ propaganda on the Omuta tourist website also fails to acknowledge the largest strike in Japan’s history – the coal miners’ strike of 1959-60 that was defeated – by Mitsui, with the support of the Japanese government.

Photos of the Miike 1959-60 strike by Japanese workers, supported by the Omuta community. Clash with police in left photo; miners’ wives in right photo. Source: Unknown autßhor – Japanese book “Album: The 25 Years of the Postwar Era” published by Asahi Shimbun Company.

Japan’s historical misrepresentation at the Miike Coal Mine stands in stark contrast to how Germany and Austria have openly acknowledged their past treatment of forced laborers, including POWs, under the Third Reich. The Japanese people can benefit from knowing their country’s history and acknowledging the crimes of the past, while finding ways to honestly build new relations internationally with countries victimized by that past, as Germany and Austria have sought to do.

South Korea raised concerns in 2020 about Japanese government failure to abide by the agreement reached in 2015, Decision 39 COM 8B.14 of the World Heritage Committee regarding full consultation with all affected parties related to the “Sites of Japan’s Industrial Revolution,” which included Mitsui’s Miike Coal Mine.45 It is imperative that the Australian government, which has a representative on the World Heritage Committee in 2021, support these concerns. History should not be reduced to bland, falsified tourist nostalgia. Public history requires accuracy, honesty, and compassion for those who paid with their lives for a country that waged a brutal war in the Asia Pacific.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @crg_globalresearch. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

David Palmer is Associate in History at The University of Melbourne. He is the author of Organizing the Shipyards: Union Strategy in Three Northeast Shipyards (Cornell UP); “Foreign Forced Labor at Mitsubishi’s Nagasaki and Hiroshima Shipyards: Big Business, Militarized Government, and the Absence of Shipbuilding Workers’ Rights in World War II Japan,” in van der Linden and Rodríguez García, eds, On Coerced Labor: Work and Compulsion after Chattel Slavery (Brill); and other publications on the labor history of the U.S. and Japan. [email protected]

Notes

1 Roy Whitecross, Slaves of the Son of Heaven: A Personal Account of an Australian POW, 1942-1945 (East Roseville, NSW: Kangaroo Press, 2000 – originally published in 1951), pp. 180-182.

2 David Palmer, “Gunkanjima / Battleship Island, Nagasaki: World Heritage Site or Urban Ruins Tourist Attraction?” The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, vol. 16, issue 1, number 4, Jan. 1, 2018.

3 Anna Bruce-Lockhart, “These are the top countries for travel and tourism in 2019,” World Economic Forum, Sept. 4, 2019.

4 “International Tourism,” The World Bank.

5 UNESCO, World Heritage Committee, “Japan: Properties Inscribed in the World Heritage List.”

6 Even conservative historians of the industrial revolution highlight the centrality of the shift from artisan and manual labor to collective (factory) and mechanized labor for the industrial revolution in Europe and the United States. See David S. Landes, The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present (Cambridge U.P, 1969); Alfred D. Chandler, The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (Harvard U.P., 1977).

7 Japanese document cited in “Follow-up Measures concerning the Inscription of the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution on the World Heritage List,” Non-paper addressed to World Heritage Committee Member States, Republic of Korea, June 26, 2020.

8 “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution” – Japanese website version, Meiji Nihon no sangyo kakumei isan.

9 Tanaka Satoko, “Rodosha no gisei ni miru senzen no Miike Tankō okeru romuseisaku no hensen to rōdōsha teikō ni kansuru kosatsu,” Bukkyo University Bulletin, Shakai fukushi gaku kenkyū rishū (Social welfare research university documents), no. 7, March 2009, p. 46; Takeuchi Yasuto, Korean Forced Labor Investigation: Coal Mines Volume (Chōsa: Chōsenjin kyōsei rōdō – Tankō shu), Tokyo, 2013, p. 132; Takeuchi Yasuto, Wartime Korean Forced Labor: Investigation Documents (Senji chōsenjin kyōsei rōdō chōsa shiryō shu), p. 211.; Tanaka Hiroshi, Record of Chinese Forced Labor: Documents (Chūgojin kyōsei renkō no kiroku: Shiryō) (Tokyo, 1990), pp. 541, 542; “Fukuoka POW Camp #17 Omuta” spreadsheet, Center for Research: Allied POWs under the Japanese – http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/fukuoka/fuku_17/fukuoka17.htm . The Korean death count is almost certainly higher than this figure. Takeuchi had to rely on two government reports (issued in 1946) and a company report on the mine. His figures for conscript numbers cover 1942-1945. Figures for Japanese employees are averaged from Tanaka’s numbers over the full six years. Australian numbers begin in 1944, American, British and Dutch numbers earlier. Aside from POW numbers, which are verifiable through multiple government documents, these figures are approximations using available sources. The Japanese numbers are the most problematic. This issue can only be resolved when Mitsui makes public its company records for this period.

10 Miyamoto Takashi, “Convict Labor and Its Commemoration: The Mitsui Miike Coal Mine Experience,” The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, vol. 15, issue 1, no. 3, Jan. 1, 2017.

11 Yamamoto Sakubei to tankō no kiroku (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 2014).

12 Japan’s claim to these sites having “outstanding universal value,” a crucial criterion for World Heritage listing, includes this statement: “The technological ensemble of key industrial sites of iron and steel, shipbuilding and coal mining is testimony to Japan’s unique achievement in world history as the first non-Western country to successfully industrialize. Viewed as an Asian cultural response to Western industrial values, the ensemble is an outstanding technological display of industrial sites that reflected the rapid and distinctive industrialisation of Japan based on local innovation and adaptation of Western technology.” Japan’s assessment of cultural value apparently does not include its treatment of coal miners, notably its use of convict, forced, and slave labor at Miike prior to the end of World War II. “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining,” UNESCO website.

13 Richard J. Samuels, The Business of the Japanese State: Energy Markets in Comparative and Historical Perspective (Cornell U.P., 1987), pp. 68-167.

14 William Donald Smith, III, “Ethnicity, Class and Gender in the Mines: Korean Workers in Japan’s Chikuhō Coal Fields, 1917-1945,” Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin, 1999, pp. 466, 473; Tom Arents, Norihiko Tsuneishi, “The Uneven Recruitment of Korean Miners in Japan in the 1910s and 1920s: Employment Strategies of the Miike and Chikuhō Coalmining Companies,” International Review of Social History, 60, Special Issue, 2015, pp. 129-131.

15 Summary of Tanaka Naoki, Kindai Nihon tanko rōdōshi kenkyu (A Study of Coal Mining Labor History in Modern Japan), by Hatakeyama Hideki, in Japanese Yearbook on Business History, trans. Stephen W. McCallion, 1998, pp. 200-203.

16 Smith, “Ethnicity, Class and Gender in the Mines,” pp. 115, 116.

17 Arents and Norihiko, “The Uneven Recruitment of Korean Miners in Japan,” pp. 121-143.

18 Priscilla Long, Where the Sun Never Shines: A History of America’s Bloody Coal Industry (New York: Paragon House, 1991), p. 41.

19 William R. Nester, Japanese Industrial Targeting: The Neomercantalist Path to Economic Superpower (Palgrave Macmillan, 1991), p. 127.

20 Ta Chen, “Labor Conditions in Japan,” Monthly Labor Review, Nov. 1925, pp. 8-19.

21 Michael Coulson, History of Mining: The Events, Technology and People Involved in the Industry in the Modern World, (Harriman House Publishing, 2012), pp. 226, 227; Keith Dix, What’s a Coal Miner to Do? The Mechanization of Coal Mining (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1988), pp. 29-34.

22 Smith, “Ethnicity, Class and Gender,” pp. 92-138.

23 See, for example, Regine Mathias, “Female Labour in the Japanese coal-mining industry,” in Janet Hunter, ed., Japanese Working Women (Routledge, 1993), pp. 98-121; Sachiko Sone, “Japanese Coal Mining: Women Discovered,” in Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt and Martha Macintyre, eds., Women Miners in Developing Countries (Ashgate, 2006), pp. 51-72; W. Donald Smith, “Digging through Layers of Class, Gender and Ethnicity: Korean Women Miners in Prewar Japan,” in Lahiri-Dutt, Macintyre, pp. 111-130; Matthew Allen, “Undermining the Occupation: Women Coal Miners in 1940s Japan,” Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, July 2010. Mathias and Sone deal with Miike, but not beyond the 1920s. Developments in the 1930s through 1945 reveal how Japan’s coal mining industry not only stagnated, but went backward, with the exclusion of women from underground at the largest mines part of this process.

24 Sakamoto Masako, Zaibatsu to teikoku shugi: Mitsui Bussan to Chūgoku (Tokyo: Minervashobo, 2004), pp. 42, 123.

25 John G. Roberts, Mitsui: Three Centuries of Japanese Business (New York: Weatherhill, 1974), p. 351.

26 Genbaku shibaku kiroku shashinshū (Photographic Collection of Atomic Bomb Photographs), Nagasaki City, 2001, p. 1 (map of Nagasaki City sites bombed); Takeuchi Yasuto, Wartime Korean Forced Labor: Investigation Documents (Senji chōsenjin kyōsei rōdō chōsa shiryō shu), Kobe, 2015, p. 115.

27 Information on Fukuoka 17 and the Miike Coal Mine in sections that follow come from interviews with David Runge and Ian Duncan, as well as David Runge’s affidavit for postwar War Crimes trials, unless otherwise indicated. David Runge interview, with Margaret Evans, March 28, 1983, accession number SO2948, Australian War Memorial Archives; Ian Duncan interview, with Margaret Evans, May 13, 1982, accession number SO2986, Australian War Memorial Archives. and David Runge affidavit for War Crimes trial, Australian War Memorial Archives, series no. AWM 54, control symbol 1010/4/125, DPI: 300. Tim Bowden organized over one hundred interviews with former Australian prisoners-of-war through the Australian War Memorial, which were for Hank Nelson’s ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) radio series, produced by Bowden, “Prisoners of War: Australians under Nippon.” ABC published a book version by Nelson in 1985.

28 Linda Goetz Holmes, Unjust Enrichment: How Japan’s Companies Built Postwar Fortunes using American POWs, (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001), p. 84, quoted in William Underwood, “The Japanese Court, Mitsubishi and Corporate Responsibility to Chinese Forced Labor Redress,” Japan Focus, March 29, 2006.

29 Frances Miley and Andrew Read, “In the Valley of the Shadow of Death: Accounting and Identity in Thai-Burma Railway Prison Camps 1942-1945,” paper presented at 14th World Congress of Accounting Historians, 2016, p. 5. In 1942, Australia’s population was over 7 million, while Great Britain’s was over 50 million, yet the number of Australian POWs in the Thai-Burma construction camps was 13,004, with 2,802 deaths, while British POWs numbered 30,131, with 6,904 deaths.

30 Australian Infantry Force.

31 Whitecross, Slaves of the Son of Heaven, pp. x, 182. “Railroad of Death” is a memoir of the Thai-Burma railway construction by former Australian POW Lieutenant John Coast, quoted in the 1951 “Forward” to Whitecross’s book, written by Adrian Curlewis, District Court Judge and former POW in Changi and on the Thai-Burma railway.

32 Australian Army Medical Corps.

33 William Green, “The General Courts Martial of Lieutenant Commander Edward N. Little,” The Text Message, National Archives (US), Nov. 13, 2018.

34 George Weller, ed. by Anthony Weller, First into Nagasaki: The Censored Eyewitness Dispatches on Post-Atomic Japan and Its Prisoners of War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2006), p. 57.

35 Whitecross, Slaves of the Son of Heaven, p. 196.

36 Weller, First into Nagasaki, p. 51.

37 Whitecross, Slaves of the Son of Heaven, p. 181.

38 Tom Uren, Straight Left (New South Wales: Random House, 1995), pp. 46-53.

39 Nozoe Kenji, Shirizu: Hanaoka jiken no hitotachi – Chūgokujin kyōsei renko kiroku (Tokyo: Shayo, 2007).

40 Email correspondence from Michael Bell, Australian War Memorial, and Felicity Perrers to Bell, July 13, 2021, citing government and family records, and newspaper obituaries; Attestation Form for Dave Runge, Australian Military Forces, July 18, 1940, National Archives of Australia, service number NX 65609.

41 Damper is unleavened soda bread of Aboriginal origin, common everywhere in Australia in modern times. It has never had any racial connotations in Australian popular culture but has always had strong links to working class culture.

42 Japanese civilian guard Takeda Sadamu, who was probably “The Sailor” who tortured Runge, was tried for war crimes. This accusation was one of a number used against him. He was convicted and sentenced to death. “Defendant: Takeda, Sadamu, Civilian Employee, Japanese Army, Fukuoka POW Branch Camp No. 17, Kyushu, Japan,” Docket No./ Date: 130/ Apr. 15 -25, 1947, Yokohama, Japan, summary on War Crimes Studies Center, U.C. Berkeley.

43 Whitecross, Slaves of the Son of Heaven, p. 231.

44 “Follow-up Measures concerning the Inscription of the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution on the World Heritage List,” Non-paper addressed to World Heritage Committee Member States, Republic of Korea, June 26, 2020.

45 “Follow-up Measures,” ROK.