Nepal’s Economy – Can Contented Tourists Match Desperate Migrant Laborers?

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above

A busy air route between Kathmandu’s Tribhuvan Airport and overseas is via the communications hub of The Arab Emirates. Several direct flights between Abu Dhabi or Doha and Nepal depart and arrive daily. Appearing unremarkable (on any day or year over the last decade), any assemblage of passengers, outbound or inbound, itself informs the character of Nepal’s impoverished (sic) economy:- workers remittances–the major sector– foreign aid, and tourism.

Making my way into and from Nepal through Arab Gulf airports on a regular basis over many years, I note a consistent composition of the 200 or so people on these flights. Inbound and outbound, they offer as genuine a portrait of the country’s economy as any generously funded study by a team of economists.

Travelers on these flights fall into three distinct groups—

1) Nepali youths employed overseas;

2) tourist-trekkers;

3) economic development personnel.

Those occupying the majority of seats, 75% or more, are young Nepalese– mostly men, most under 30. They dress similarly—a simple shirt and trousers, maybe a thin jacket. They check into their flight with a light knapsack or carry-on suitcase. If outbound from Nepal they sport fresh haircuts; around the necks of some hang silken kathak— good luck scarves offered by well-wishers.

In the departure lounge at Tribhuvan Airport, these men may appear shy. Once boarded and secure in their seats, their emotion blooms as if, until then, they’d remained uncertain if they might leave the ground. Now Nepali phrases sweep around the rows of seats throughout the four-hour flight, a relaxed animated dialogue that suggests these men are old friends. In fact most, until now, were strangers.

These Nepalis’ demeanor contrasts with the minority passengers, ‘westerners’ –European, American, Australian or New Zealander– varying in age from 20 to 70, sometimes older and generally traveling in couples. They too carry little more than a single backpack, but double or triple the size of the Nepali youths’ gear, each branded with a recognizable sports logo. Whatever the weather, these vacationers clutch water bottles and wear sturdy climbing boots.

If a Business Class is designated on these short flights, you’ll find there a handful of sedate travelers, a mixed but mainly white group. Dressed casually–no sign of backpacks or climbing boosts here—they’ll tote only a computer bag. These subdued women and men are ‘development’ experts– in Nepal to assist (with anything)– Red Cross, UNICEF, Medicine Sans Frontiers, Norwegian hydroelectric engineers, Microsoft educational consultants, democracy monitors, Australian gender analysts, pollution appraisers and endless other NGO project staff. From the moment they’re seated, they flip through graph-laden reports, phone in hand — all destined for yet another conference. (At the time of Nepal’s 2015 earthquake, journalists’ crowded these flights alongside NGO emergency personnel, temporarily replacing tourist travelers. Although most seats were taken by Nepali sons rushing home out of concern for loved ones.)

There you have it: the Nepal economy in a single flight.

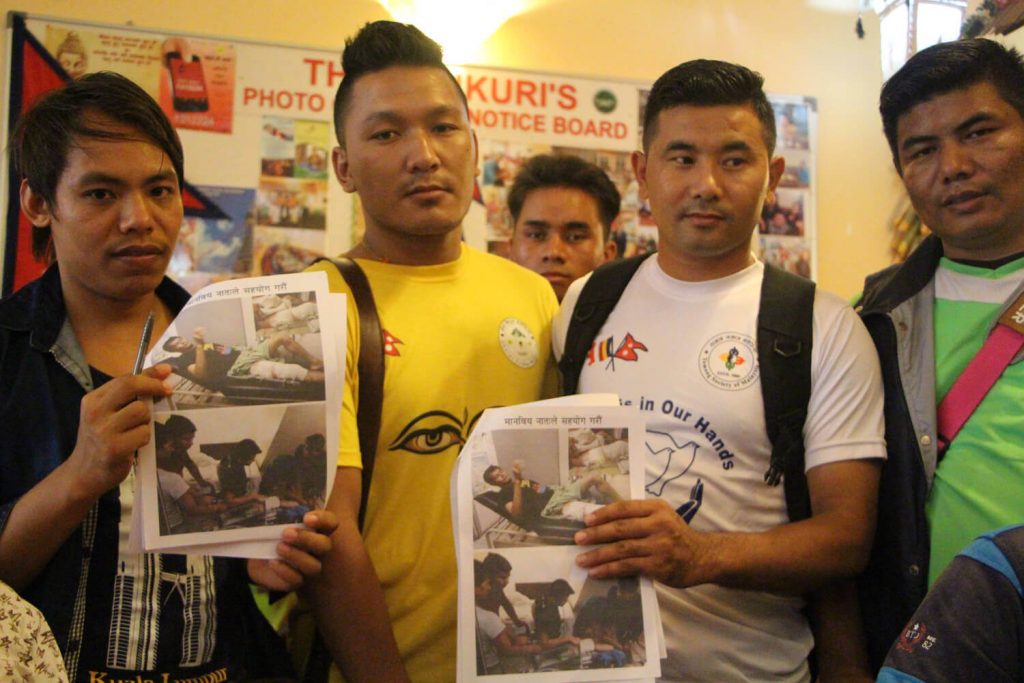

The young Nepali men on the flight are all migrant laborers drawn from every corner of the nation, from a range of ethnic group. They are drivers and masons, carpenters and farmers– lads with a few years of schooling, all new to international travel, all hopeful. Some are urban born, others villagers who’ve taken on debt to pay the fees necessary to secure overseas work. A fraction of these youths head to Malaysia; most are destined for The Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Together they constitute a force estimated to be as high as seven million Nepali laborers (officially reported as close to 4 million) employed abroad in estates, stadiums and museums, restaurants and malls, offices, houses and farms. See this. (Some drivers or cooks are recruited by American security agencies in Iraq. A few migrants, mainly women, become domestics in the Arab Gulf, but most travel to Lebanon and Israel to work for families there.)

The white passengers in economy class are tourists. They’re working people who’ve saved for a year or more for their enchanted Himalayan holiday. They are a happy lot, the tourists—people infinitely patient over delayed flights and uncomplaining about days bedridden with an intestinal disease. Once airborne, they speak in whispers, while engaged writing blogs.

Tourists toNepal number nearly a million annually. Their contribution to the economy (contrary to claims in Wikipedia) however amounts to barely five percent because the business is highly centralized, visitors’ stays are short, and cheap lodgings are plentiful. (Following the earthquake, Nepal’s sophisticated tourist industry bulletins sounded an alarm of the quake’s impact on tourism. Although exaggerated, this helped mobilize funding for immediate restoration of notable temples and trekking routes. Tourist needs seemed to take priority in contrast to thousands of damaged village dwellings and public schools– a responsibility of the Nepali government—still awaiting repair.)

As for the non-governmental organizations, their economic impact derives less through assistance to the needy, than from their bureaucratic structures centered in the capital. Charitable fees for visiting consultants may come from headquarters. No, it’s in the sprawling local agencies where we find a significant impact on Nepal’s economy. Here, tens of thousands of salaried staff dispense (foreign aid) money into the market to sustain themselves and their offices. Together with civil servants whose salaries are supplemented by payoffs from agencies and businesses, this community now constitutes the core of Kathmandu’s sizable middle class. House owners rent to NGOs, restaurants and shops offer an atmosphere and cuisine worthy of internationals, along with staff (gardeners, drivers, cleaners, etc.) who manage their homes and offices. Many tens of thousands live off aid flowing into Nepal. They in turn need vehicles, electrical generators and washing machines; they build gated homes and hire local agencies to arrange their travel and chauffeurs to drive their children to exclusive private schools. They gather at the glass malls and shop at brand-named stores and restaurants along Durbar Marg.

This conspicuously wealthy population of Kathmandu has emerged out of the 20,000 or more NGOs based here that offer Nepaleverything— from city sanitation services to a surfeit of agencies sheltering women and researching hydro-power–whether or not the nation really needs them. Although a substantial element in the city’s economy, NGO financial input does not register in any official assessment of Nepal’s economy.

In any case, the mainstay of the nation’s economy lies elsewhere. It derives from the accumulated impact of cash remittances to their families from those anxious lads who boarded planes for jobs abroad—feckless workers often characterized as exploited labor.

Some mistreatment is undeniable, just as contract freelance workers catering to the needs of New Yorkers or Londoners are exploited. But these millions of migrants laboring where they can never become citizens transfer billions of dollars in earnings home. That is having a profound impact on Nepal’s economy. And even though that economic stimulus may be misplaced—because it drives consumerism rather than labor-intense local industries, it still transforms the life of these youths and their families that economic development plans could not.

(This dynamic, we will explore in the next of our series on Nepal.)

*

Aziz is the author of Heir to A Silent Song: Two Rebel Women of Nepal, published by Tribhuvan Universityin Nepal, and available through Barnes and Noble. She is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Featured image is from an Asia Society report.