The Sado Gold Mine and Japan’s ‘History War’ Versus the Memory of Korean Forced Laborers

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @globalresearch_crg and Twitter at @crglobalization.

***

Abstract

Japan has nominated the Sado Gold Mine for UNESECO World Heritage inscription despite South Korean opposition due to Japan’s refusal to recognize the role of wartime Korean forced labor at this location. Japan’s previous industrial World Heritage inscription is criticized for similar denials of forced labor history. In this way, the Japanese government has embarked on a “history war” against Korea and the memories of the wartime victims of forced labor. In addition to providing victim testimony, historical sources and local and Korean research reveals that Mitsubishi forced Korean laborers to work in deadly conditions in the Sado mines. Korean forced laborers were taken to Sado Island where they faced racial discrimination and abuse. This article explains why Japan chose to worsen relations with Korea by nominating the Sado mines for World Heritage inscription while concealing the use of forced Korean labor and examines evidence of forced labor at the site.

*

On January 28th 2022, Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio announced plans to proceed with the UNESCO World Heritage nomination of the “Sado Gold Mine”, or more accurately the “Sado complex of heritage mines, primarily gold mines” (hereafter Sado mines).[1] The announcement further soured Japan-South Korea relations, as Korea strongly opposes the nomination due to Japan’s denials of Korean forced labor at Sado and other sites during wartime. Kishida’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) government was considering postponing the nomination due to Korea’s protests, but the decision to go ahead immediately was made at the insistence of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzō.[2] Abe, who still heavily influences the LDP, stated officially on January 20th 2022 that it would be a mistake not to nominate the Sado mines in order to avoid controversy.[3] Following Abe’s bidding, Kishida established a “history war team” within the cabinet with the purpose of “collecting facts for inspection to gain understanding from the international community based on the [Japanese] government’s perception of history.”[4] Foreign Minister Hayashi Yoshimasa announced that the Japanese government “is not giving any diplomatic consideration to South Korea” in this matter. [5]

The Sado mines were bought from the government in 1896 by Mitsubishi, which operated the mines during wartime and until their closure in 1989. In an interview published on the first page of Shūkan Fuji, January 26th 2022, Abe Shinzō again denied the wartime use of Korean forced labor at the Sado mines, citing two history books by Mitsubishi.[6] One of these books had a week earlier been cited to disprove the use of forced labor by a member of parliament representing Niigata.[7] Needless to say, history written by the perpetrator is not adequate for disproving allegations of victims.

Dōyū nowarito outcrop in Aikawa, Sado. The mountain was split by Edo period surface mining.

Photo by Muramasa (CC), Wikimedia Commons, 2013.

“The Second Battleship Island”

The announcement of plans to nominate the Sado mines for UNESCO World Heritage inscription in 2023 came in the middle of another ongoing dispute over Korean forced labor history at Japanese industrial heritage sites. The Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining (hereafter the Meiji Industrial Sites), were inscribed by UNESCO in 2015, on the agreed condition that Japan acknowledge that “a large number of Koreans and others […] were brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions in the 1940s at some of the sites.”[8] However, the Industrial Heritage Information Centre that opened in Tokyo ostensibly with the purpose of acknowledging these victims instead denies the history of forced labor and even discrimination against Koreans at the inscribed sites.

Like the Sado mines, five of the inscribed Meiji Industrial Sites with Korean forced labor history, including the infamous “Battleship Island/Gunkanjima” (Hashima), were owned and operated by the Mitsubishi group during the war. Previous examination of the nomination process and development of the controversial Industrial Heritage Information Centre revealed that its historical negationism was backed and encouraged by Abe Shinzō, and that his close friend Kato Kōko along with elite businesspeople within and/or with close ties to Mitsubishi were directly responsible for the data collection which formed the basis for the center’s exhibitions.[9] UNESCO has given Japan a deadline of December 1st 2022 to report updated steps to improve the historical narratives at the center.

Pushing for the World Heritage inscription of yet another industrial site with a history of wartime Korean forced labor naturally attracts unwanted attention in Japan concerning its dark colonial history. Recent South Korean media reports frequently refer to the Sado mines as “the second Battleship Island.”[10] Why nominate the Sado mines for World Heritage inscription when it attracts attention to a history Japan would like to forget?

Behind the World Heritage Nomination of the Sado Mines

Sado Island is located in Niigata Prefecture about 30 km from the mainland and is roughly two thirds the size of Okinawa Island (855 km²). The population is approximately 56,000 (as of 2018).[11] Sado is known for agriculture and fishing, but the Sado mines were also domestically well-known before its World Heritage nomination. Even so, the number of visitors to Sado have steadily declined since the 1990’s. While about 1,144,000 people travelled across to Sado in the fiscal year of 1994, only about 500,000 people crossed over to the island annually in the fiscal years of 2019 and 2020.[12] This number was further halved in 2021 by the Coronavirus pandemic. In recent news reports broadcasted in Japan, people working in the Sado tourism industry have expressed their high hopes and expectations for a World Heritage inscription that could revitalize tourism on the island.

Google map with Sado Island encircled, Feb. 2022.

In order for any country to nominate a site for World Heritage inscription, the site must first be included in the country’s Tentative List.[13] The first application to register the Sado mines was filed jointly by Sado City and Niigata Prefecture in 2006.[14] This was the very first year it become possible for local governments to do so in Japan, as it had previously been up to the national government.[15] As the initial underdeveloped application failed, the prefectural government established an official Niigata World Heritage registration promotion office.

“The Sado complex of heritage mines, primarily gold mines” was approved for the Tentative List by the Agency of Cultural Affairs in 2010. The focus was now on primarily on gold, in contrast to the first application which was titled “Sado, the island of gold and silver: mining and culture.” Over a period of about 400 years of mining, the Sado mines produced 2300 tons of silver, and 78 tons of gold.[16] The approved application did not ignore Sado’s silver production, but goldmining was made central to the claim that the mines have Outstanding Universal Value (OUV)—an essential criteria for World Heritage recognition.

Japan’s claims for OUV of the Sado mines in 2010 included the culture that developed there for over 400 years of goldmining and “the constant introduction of mining techniques and technical expertise from both Japan and abroad […].” The OUV justification specifies “the Nishimikawa alluvial gold deposits and the Dōyū-nowarito outcrop” as “outstanding example[s] of a technological ensemble.” Emphasis is put on the Edo-period “gold coinage system manufactured at the Sado Mines” and the Sado mines’ historical influence on international economy.

Value of the Sado mines as Industrial Heritage

The uniqueness of the Sado mines as an industrial heritage site can be disputed.[18] Japan’s interpretation of the mines’ history is selective and celebratory, but arguably, the mines are cultural and historical assets worthy of preservation for future generations. In 1601, two years before the Tokugawa Shogunate started its 265 year long military rule of Japan (the Edo-period), Tokugawa started developing the Sado Aikawa gold and silver mine. Miners from all over Japan gathered on Sado which became the biggest and most important gold and silver mines in the country. Although generally primitive, endogenous mining techniques developed on Sado.[19] The Sado mining community spawned unique cultural aspects, such as “demon drums” (Onidaiko).[20] Since the Edo-period, locals with demon masks and mining chisels have danced to traditional taiko drums on Sado during festivals, a custom continued and highly valued to this day.[21]

The Sado mines are also important heritage sites due to their iconic history of prison labor. In his introduction to Japanese prison labor, Tanaka Mitsuo asserts that “prison labor history [in Japan] is extensive, and the most famous example is the Sado mines,” referring to the Edo-period.[22] Since 1778, homeless people in Edo and other cities were rounded up and transported to the Sado mines for slave labor. Illegal gambling rings were raided to catch groups of prisoners for mining. The Japanese word “dosakusa,” meaning “a confusing and chaotic situation,” is said to stem from “dosa”—Edo-period slang referring to illegal gamblers escaping in all directions and sent to the Sado mines (“do-sa” is “Sa-do” spelt backwards in Japanese).[23] Records show that lung disease due to inhalation of silica dust significantly shortened the lives of Edo-period Sado mine laborers.[24] Most of the prison laborers pumped water out of the mines which were susceptible to flooding, and it is estimated that 1,800 laborers died in the Sado mines in the last 100 years of the Edo-period.[25]

At the beginning of the Meiji Era, the Meiji government took control of the mine. To remedy decreased production, foreign mining experts from England, Germany and the US were brought to Sado to set up Western modernized mining facilities.[26] The foreign mining experts advised the discontinuation of ineffective endogenous techniques, many of which had been developed by the miners themselves.[27]

Mitsubishi’s Sado Mines

Mitsubishi purchased the Sado mines from the Meiji government in 1896, which was excellent timing.[28]The demand for gold soared when Japan placed the Yen on the gold-standard in 1897, meaning that the value of the Yen was based on a fixed amount of gold. The background was that Japan mainly bought warships, munitions, and machinery from gold-standard countries like Britain, which was becoming increasingly expensive for Japan due to the global depreciation of silver. After the first Sino-Japanese war (1894-95) in which Japan gained power in Korea by defeating China, Japan received from China an indemnity in gold worth £38 million British Pounds. With this indemnity Japan obtained sufficient reserves to satisfy the Bank of England and to switch to the gold standard.[29] Mitsubishi’s Sado gold could then be exchanged for Western warships and weapons helping Japan win the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). Russia’s defeat removed the final obstacle to making Korea a Japanese Protectorate (1905-1910) and subsequently a colony of Japan (1910-1945).

By 1897, 2224 laborers at Mitsubishi’s Sado mines produced gold, silver, and copper.[30] The majority of workers were Japanese, recruited from outside Sado Island by contractors.[31] Rather than paying the laborers directly, Mitsubishi paid the contractors who provided food and dormitory (takobeya) space and became wealthy from deducting fees from their contracted workers’ wages. Around the turn of the century, Mitsubishi was notorious for its mistreatment of contracted laborers after journalists worked undercover in their coal mines and exposed the lack of freedom of movement and violent punishments inflicted by overseers.[32] Also in the Sado mines, hundreds of miners launched disputes and strikes between 1899-1922 to protest unacceptable conditions.[33] From 1926, a new system was implemented in the Sado mines in which laborers were directly employed and paid by Mitsubishi, but the previous system was not completely phased out until 1935.[34]

Mitsubishi[35] centered all its efforts in the Sado mines on gold from 1931 when Japan instigated the second Sino-Japanese war. The company group built new facilities to produce additional gold on Sado, in order to meet the government’s rising demands. Japan needed funding for the purchase and transport of military supplies to its forces invading China.[36] The Kitazawa Floating Plant, the only floating plant in East Asia at the time, was expanded for this purpose in 1938.[37] The Kitazawa Floating Plant is the visually most impressive industrial ruins in the Sado mine complex, and its image is frequently used to promote the Sado mines. Sado’s most successful year in terms of gold production was 1940 when, in the midst of the Asia-Pacific War, 1537kg of gold were produced. This was almost double that of 1938, made possible with the use of Korean forced laborers whose massive mobilization was initiated in 1939.[38]

In 1952, Mitsubishi closed many of the Sado mine tunnels and reduced the number of employees to one tenth.[39] In 1962, the company opened parts of the mines for commercial tourism. Mining operations were closed permanently in 1989, as minerals were deemed depleted. Ownership was passed to Golden Sado Inc. which to the present manages the mines for tourism. In addition to an exhibition hall and outdoor industrial heritage, tourists can join tours inside mines including the Edo-period Sōdayū-tunnel and the Meiji-period Dōyū-tunnel.[40] Golden Sado Inc. is a Mitsubishi subsidiary which is owned 100% by the Mitsubishi Materials Corporation.[41] The World Heritage nomination is thus another golden opportunity for Mitsubishi itself, as the conglomerate can pocket increased revenues through the tourism boost a World Heritage inscription will facilitate without having to acknowledge the role of forced labor in the wartime mines.

The Kitazawa Floating Plant. Photo by Itō Yoshiyuki (CC), Wikimedia Commons, 2013.

Absorbed into the History Wars

The reason behind Japan’s insistence on inscribing yet another site of Korean forced labor for World Heritage now, is that local Sado Island tourism promotion has peaked at the same time that Japanese efforts to deny forced labor at “Battleship Island” and other Meiji Industrial Sites inscribed as World Heritage peaked since 2015.[42] The National Congress of Industrial Heritage (managed by Katō) has received great sums of money from the LDP government spent on the Industrial Heritage Information Centre (also managed by Katō), which despite criticism from UNESCO continues to deny both Korean forced labor and discrimination against Koreans at the Meiji Industrial Heritage Sites. As Abe has correctly implied, hesitating to nominate the Sado mines could send a signal that Japan acknowledges the need to scrutinize its wartime forced labor history.

At the same time, Mitsubishi is facing many lawsuits by descendants of victims of forced labor at a multitude of the company’s sites across Japan. The fact that Mitsubishi itself is still deeply involved with both the Meiji Industrial Sites and the Sado mines is one reason that acknowledging forced labor history is not considered an option by Japan.

In the case of the Meiji Industrial Sites, testimony from many Korean and Chinese victims as well as from Western POWs are known. In the case of the Sado mines, there are no known foreign victims except Koreans, and only a single direct Korean testimony of forced labor in the Sado mines is known. Japan may not perceive the Sado mines nomination as posing any new problems—it may only exacerbate already tense Japan-Korea relations. However, Japan is wrong to assume that only Koreans value the memories of Korean victims.

Im T’aeho’s Memories of Forced Labor in the Sado Mines

The aforementioned single Korean testimony was given by Im T’aeho (임태호/林泰鍋) in May 1997, a few months before he passed away. His oral testimony was recorded by his third daughter, Im Kyŏngsuk, and published in Japan in 2002.[43] Recent interviews with Im Kyŏngsuk and Im T’aeho’s oldest daughter, Im Kanran, provide new details not recorded in his testimony.[44]

Im Kyŏngsuk and Im Kanran with pictures of their father, Im T’aeho. Picture captured from the Chosun Ilbo website, 20 Jan. 2022.

Im T’aeho was born December 20th 1919 in Nonsan, Korea, where he married and lived until recruiters working for Mitsubishi came in 1940. Im T’aeho’s wife gave birth to their first daughter Im Kanran in Nonsan the same year. Nonsan was impoverished and Im T’aeho could not find work there to support his new family. He was enticed by the promises of the recruiters and saw no other option but to relocate his family to Japan where family housing, food, and work was guaranteed by Mitsubishi. 20-year-old Im T’aeho crossed the ocean first on a narrow boat crammed full of others like him, and his family followed soon after.

Upon arrival at Sado Island in November 1940, Im T’aeho was taken deep into the mountains of Aikawa. Far from a comfortable family apartment, he was placed in a remote and crammed dormitory (hamba). His testimony states he realized that he would be mining minerals for Mitsubishi in the Sado mines and that he had lost his freedom. His wife and infant daughter also lived in the dormitory together with many other miners. Im T’aeho’s wife gave birth to two more daughters while living there.

Im T’aeho worked every day from morning until night, mining for minerals deep inside the dusty mines. He stated that cave-ins happened almost every day and that remains of Koreans who died were not treated with any respect by Mitsubishi. This heightened his constant death anxiety. The approximately 90-minute walk back from the mines to the dormitory at night were excruciating. It was a difficult and mountainous path with heavy snowfall in winter, reaching high above Im T’aeho’s knees.

Im T’aeho sustained serious injuries due to two accidents in the mines. The first time, a ladder inside the mines fell as he was climbing it, causing permanent injuries to his hip and leg. Im T’aeho regained consciousness after being carried back to the dormitory—not the hospital. According to his testimony, he was not offered any treatment and was unable to walk to the hospital himself. He was forced back into the mines as soon as he could stand up after about ten days in the dormitory. Soon after, he sustained another injury rendering his hand unusable. At that point, he realized that he could not survive the rigors of the labor much longer.

Im T’aeho managed to escape from Sado Island with his wife and three young daughters.[45] Korean forced laborers only received a fraction of their promised wages, and Im T’aeho had no money after the escape. Im and his family wandered around Japan, and were in Kawasaki when the war ended in August 1945. He was emotionally overwhelmed and could only shed tears of relief upon hearing the news that Korea had been liberated and he was freed from the chains of imperial Japan.

Despite suffering from trauma, mining injuries and silicosis, Im T’aeho lived until the age of 77. Silicosis is a lung decease caused by prolonged inhalation of mineral dust (silica) that makes it progressively harder to breath, decades after first exposure.[46] According to his daughter Im Kyŏngsuk, Im T’aeho developed lumps in his lungs the size of marbles, which eventually caused his slow and agonizing death in 1997. His stated hope of someday receiving an apology from Japan was futile. Im T’aeho’s children oppose the World Heritage nomination of the Sado mines because Japan selectively presents celebratory narratives while concealing shameful parts of history, including the story of their father.

Historical documents and previous research prove that Mitsubishi used Korean forced laborers at the Sado mines during wartime. An extensive Korean investigation report on Mitsubishi’s wartime forced labor in the Sado mines from 2019, headed by Chŏng Hyekyŏng for the Foundation for Victims of Forced Mobilization by Imperial Japan, confirms this history building on multiple primary and secondary sources.[47] These include Japanese colonial police reports, newspapers, name lists, interviews with seven families of deceased victims, as well as earlier Japanese academic investigations.[48] One of the latter is Hirose Teizō’s research conducted in the 1980’s.[49] Hirose, a local historian at Niigata University fluent in Korean, has interviewed both elderly local Sado residents as well as Korean victims of forced labor in the Sado mines.[50] Official Japanese local history books from Sado City and Niigata Prefecture also describe Korean forced labor in the Sado mines.[51] Numerous publications document Korean forced labor at other Mitsubishi sites, adding context for interpreting the case of the Sado Mines.[52]

Korean Colonial Subjects in Pre-War Niigata

Korean laborers already worked in the Sado mines before forced mobilization and forced labor programs for Koreans were initiated by the Japanese government in 1939. Following Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910, the number of Koreans in Japan started to increase rapidly. The Korean population of Niigata Prefecture was 11 in 1913, climbing to 1,061 in 1927, reaching 3,368 by 1938.[53] By 1929, 21 Koreans had accepted work in the Sado mines under employment by Mitsubishi.[54] Although life in Japan was not easy, some of the Korean families that lived on Sado Island in the 1930’s before the war saw the work as an opportunity.[55] Koreans were citizens of the Japanese empire. However, xenophobia and racism against Koreans was already systematic and widespread when Korean forced labor became common during wartime (from 1939) as numerous Japanese laborers were drafted into the military.

The independence movement, which began in Korea on March 1st 1919, provoked anti-Korean sentiment in Japan. On July 29th 1922, the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper reported that a great number of “corpses of massacred Koreans” were floating down the Shinano river in Niigata.[56] The background was the Shinano river incident, in which up to 100 Korean laborers at the Nakatsu Power Plant no. 1 of Shin’etsu Electric Power (currently Tokyo Electric Power Company) were massacred for attempting escape.[57] Forced labor and violent exploitation of Korean laborers was not common in Japan at this time, but according to the newspaper article, Korean laborers at the Niigata Nakatsu Power Plant were forced to work 16 hours a day by Japanese supervisors.[58] It is noteworthy that both the Niigata and Tokyo police denied that any massacre of Koreans had taken place, and media coverage immediately ceased. Locals subsequently confirmed the sightings of a large number of Korean corpses, a fact included in Niigata’s official history.[59]After the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, false reports of Koreans using the aftermath as an opportunity to plunder Japanese villages continued to be spread by newspapers, despite lack of evidence.[60] In Niigata, groups of Japanese vigilantes were guarding villages with dynamite in hand, terrified of what even the official prefectural history subsequently confirmed were “hoaxes” against Korean residents.[61] In imperial Japan, Koreans were not treated the same as Japanese.

Wartime Mobilization of Korean Forced Laborers

Mitsubishi was struggling with labor shortages in the Sado mines when the Japanese government in 1938 implemented regulations for increased production of minerals to support the war against China.[62]Japan’s National General Labor Mobilization Law, implemented in 1938, was adjusted the next year allowing Japanese companies to mobilize laborers from Korea with the aid of colonial police and authorities.[63] This wartime mobilization of Korean laborers officially started in September 1939, but Mitsubishi started mass recruitment from Korea to Sado already in February the same year. Mitsubishi’s Human Resources staff explained that “production targets [could] not be met because many of the Japanese laborers working inside the mine [were] suffering from silicosis, and more and more young Japanese [were] conscripted for military service”.[64] No known records show how many Sado mine laborers suffered from silicosis, but a Taishō-era (1912-1926) name list for the Yasuda dormitory noted 10 “suspicious deaths,” 2 deaths due to suffocation, and 122 deaths due to unknown causes.[65]

From February 1939, Mitsubishi’s recruiters for the Sado mines travelled around villages in Korea’s South Ch’ungch’ŏng Province, where Im T’aeho’s hometown of Nonsan is located. Up to 40 men from each village were made to sign three-year working contracts for labor in Japan.[66] Deception and coercion was common during the recruitment process, and force was used to keep laborers at work against their will.[67]In addition to Im T’aeho and many others, Kang Sinto, Kim Chongwŏn, and Hong Tongch’ŏl were taken from Nonsan to the Sado mines by Mitsubishi with support from the Japanese government during wartime. The aforementioned 2019 Korean investigation report, based on interviews with their families, explained that the latter three were sent back to Korea with silicosis in 1943.[68] Kang Sinto, Kim Chongwŏn, and Hong Tongch’ŏl all received disability-related financial support from the Korean government until their deaths due to their fatal decease.[69]

The 2015 survey report by the Sado City World Heritage Promotional Division gives a few more details on the February 1939 mobilization of Korean laborers for the Sado mines, based on Mitsubishi’s records.[70] It states that drought had continued for two years in a row in South Ch’ungch’ŏng Province, and suggests that this made it easy to recruit a large (unspecified) number of Korean workers. It further states that many Koreans “escaped” in Japan on the way to Sado Island because “they wanted other types of jobs from acquaintances already in Japan”. However, as we know from the context, these exploited Koreans were escaping their forced mobilization.

The forced mobilization of Korean laborers to Japan officially went through three different phases— “recruitment” (Sep. 1939-Feb. 1942), “official mediation” (until Sep. 1944), and “conscription” (until Aug. 1945).[71] It is well-known that despite misleading terms, all three periods were planned by the Japanese state and involved coercion and force by police and military when necessary. Niigata’s official history also asserts for the same reasons that “the fact that Koreans were mobilized with force” applies to all three phases.[72] During the “recruitment” period, the threat of violence was used by recruiters who worked with Korean officials. During the “official mediation” period, the Korean Labor Association handled recruitment on behalf of Japanese companies, using coercion to meet the Japanese government’s demands. Once contracts were signed by the often illiterate Korean recruits, they were taken to their place of work where they lost freedom of movement. During the “conscription” period, Japanese military police openly used violence against Koreans who had no legal way to avoid recruitment.[73]

When the first three-year contracts were about to end in 1942, Sado labor managers implemented a policy to make “everyone continue working.”[74] Mitsubishi’s records noted that local authorities and police in Korea should be consulted before sending back those that were too sick, or for other reasons could not be made to continue.[75] The official history of Niigata prefecture states that the contracts were renewed by force.[76] In February 1944, Mitsubishi built a sanatorium especially for Korean laborers, for the purpose of providing “early treatment of disease and ideological training.”[77] Rather than sending laborers back to Korea, symptoms of silicosis could sometimes be eased with medical treatment and “ideological training” could motivate, or force, sick Korean laborers to return to the mines.

In December 1944, the government issued official orders of labor conscription to all Korean and Japanese laborers in the Sado mines.[78] This officially voided end dates in contracts and made it illegal for laborers to protest. While conscripted labor during wartime is usually not legally considered forced labor, South Korea asserts that Japan’s colonial occupation of Korea was illegal and against the will of its people, and therefore the conscription of Koreans as subjects of colonial Japan was also illegal.[79]

Numbers of Korean Forced Laborers

Takeuchi Yasuto is widely cited for his statistics and calculations of numbers of Korean forced laborers in Japan, based on primary sources. He estimates that out of the approximately 800,000 Koreans forced to work in Japan during wartime, more than 100,000 worked for Mitsubishi.[80] Mitsubishi also used wartime foreign forced labor in mines and factories outside the Japanese mainland, in countries like Korea, China, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines.[81] In addition to its many famous factories and coalmines located throughout the empire, Mitsubishi used Korean forced labor for mineral mining across mainland Japan, including in their Sado mines, Ikuno mines, Akenobe mines, Osarizawa mines, Obira mines, Makine mines, Hosokura mines, Teine mines, and Shin-Shimokawa mines.[82] These mineral mines benefitted from the slave labor of approximately 60,000 Koreans.[83] About 5,000 Korean forced laborers were working in 40 different sites in Niigata Prefecture when the war ended—the Sado mines having the highest ratio.[84] Takeuchi calculates that in the Sado mines specifically, at least 1,519 Koreans were forced to work in the period from February 1940 until the end of the war.[85] This number is based on Mitsubishi’s own records, but may not include all Koreans mobilized between February 1939 and February 1940 for which period no detailed records are known.

Mitsubishi documented its mobilization of a total of 1,005 Korean laborers for the Sado mines between February 1940 and March 1942, of which 584 were still there in June 1943 (together with 709 Japanese).[86]New recruits were needed as the Korean labor force was continuously decreasing. Reasons for this includes silicosis, but also a large number of escapes and possibly unrecorded deaths. Mitsubishi’s own statistics from 1943 record 148 successful escapes (逃走) of Korean laborers between February 1940 and June 1943.[87] Mitsubishi recorded that for the same period 6 Koreans were sent home due to working injuries, and 30 more due to “personal illness”. 130 were transferred to other labor sites. The same statistics record 10 deaths of Korean laborers during this period. However, the Korean investigation report published in 2019 states that at least two deaths during this period were not recorded by Mitsubishi and suggests there may be many more. The two unrecorded deaths specifically referred to in this Korean report occurred on December 20th 1942, when falling rocks inside the mines fractured the skull of Kim Chuhwan, killing him along with another unnamed Korean laborer.[88]

Today, the names of over 500 Korean forced laborers at the Sado mines are known from a combination of name lists, including notes of distribution of tobacco rations which also included the age of laborers.[89]The 2019 Korean investigation report calculates, based on a combined list of 355 names and ages of Korean forced laborers at the Sado mines, that the average age was 28.8.[90] The ages ranged from 16 to 48, and 53% were in their twenties. Mitsubishi’s aforementioned records of Korean laborers recruited between February 1940 and March 1942 documents that 80% were from South Ch’ungch’ŏng Province (including Nonsan) and 20% from North Chŏlla Province, both in southern Korea.[91] However, other sources such as the tobacco ration list inform us that the Sado mines also recruited Koreans from South Chŏlla Province, North Kyŏngsang Province and North Ch’ungch’ŏng Province in the south, as well as from South Hamgyŏng Province which today is part of North Korea.[92]

Living Conditions

Korean forced laborers are known to have been placed in at least five different residences on Sado Island. These were Yamanogami company residence (for families) in Shimoyamagami-machi, Sōai Dormitory no.1 in Shin-Gorōno-machi, Sōai Dormitory no.3 in Suwa-chō, Sōai Dormitory no.4 in Chisuke-machi and a final dormitory referred to as Kŭmgangnyo in the 2019 Korean investigation report (possibly “Kanagawa” Dormitory in Japanese).[93] Mitsubishi’s records listed 117 Korean laborers residing in the company residence for families, and 185, 157, and 124 Koreans residing in Sōai Dormitory No. 1, 3 and 4, respectively.[94] According to the 2015 survey report by the Sado City World Heritage Promotional Division, Korean laborers were also placed in Sōai Dormitory no.2 in Shimoyamagami-machi as well as in houses in Shimoaikawa.[95] According to Sakaue Torakichi who worked as a dormitory chief for Koreans on Sado during wartime, each person was allocated the space of one tatami mat (less than 2 m²).[96]

Citing an April 14th 1941 Niigata Shimbun newspaper article, Hirose Teizō states that, in 1941, about 50 out of 600 Korean laborers on Sado lived in family apartments. However, the 2019 Korean report which included findings of investigations in Nonsan revealed that several families of now deceased Korean forced laborers lived in dormitories with other laborers on Sado island.[97] It is unclear why Mitsubishi placed several families from Nonsan in dormitories despite having family apartments on Sado, but this discovery is significant for corroborating Im T’aeho’s testimony.

Mitsubishi’s laborers did not pay for housing on Sado Island, but amongst various compulsory fees 50 zen was deducted daily for food prepared by the company, yet food was in short supply.[98] Lack of food is one of the reasons for Korean laborers attempting to escape Sado Island.[99] The Niigata Shimbun newspaper reported on April 8 1942, that hundreds of “Koreans and others” employed at Mitsubishi’s Sado mines were cultivating large amounts of vegetables in the Aikawa mountain fields, while also raising several pigs to provide fertilizer to secure sufficient food.[100] Mitsubishi’s records list vegetable and pig farming as a countermeasure for food shortage, suggesting that the vegetable fields referred to in the newspaper article were managed by Mitsubishi.[101]

The Korean laborers at the Sado mines were constantly reminded how their work supported Japanese warfare. Mitsubishi’s main gates on Sado bore the slogan: “Final victory will be achieved from exceeding production targets day by day; increase production with indomitable fighting spirit (戦意); destroy USA and England with labor and accident-prevention.”[102] Japanese students lined up in the morning greeting laborers on the way to the mines: “Good morning everyone[!] Please increase production today as well so that we can defeat our enemies, the USA and England.”[103] The week after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th 1941, a “prayer festival for the war victory of migrant Korean laborers” was held at a Shinto shrine near the Sado mines, in which about 200 Koreans were made to pray and worship the Japanese emperor.[104]

Newly arrived Korean laborers at the Sado mines received three months of language education and ideological training.[105] Many of the Korean farmers selected for mining could not speak Japanese, but in contrast to the coal mines, comprehension of instructions was essential in the mineral mines. The ideological training was also spiritual or religious in nature. A central part of the “Japanification” of Koreans was Shintoism and worship of the Japanese emperor as a descendant of Shinto deities. The fact that such training continued even in the Korean sanatorium illustrates the extent of proselytism. Korean resistance to Shintoism is evident in the fact that large groups of Koreans tore down the Japanese shrines in their country very soon after liberation.

Working Conditions

Korean forced laborers in the Sado mines faced extreme discrimination with potentially fatal outcomes. The majority of the toughest and most dangerous positions deep in the mines, where cave-ins were common and constant inhalation of silica dust was unavoidable, were filled by Koreans.[106] Records of most cave-ins are not available, but a 1935 Niigata Shimbun newspaper article states that on average one laborer per day was injured from accidents in the Sado mines, which is consistent with Im T’aeho’s memories of wartime labor there.[107]

As Niigata’s prefectural history documents, job assignments at the Sado mines were discriminatory towards Koreans.[108] Underground rock drilling, tunnel underpinning, and underground transporting of produced minerals were especially dangerous jobs.[109] According to the Mitsubishi report from June 1943, 76% of laborers assigned to these positions were Korean (146 Japanese versus 473 Koreans).[110] 82% of rock drillers were Korean (27 Japanese versus 123 Koreans). Only 18% of smelters, who did not work inside the mines, were Korean (85 Japanese versus 19 Koreans). Some of Mitsubishi’s job categories are vague, such as those of kōsaku (possible interpretations include craftsmen and machinists) and zatsufu/zōfu (helper, or literally someone who does various jobs). Only 26% of laborers assigned these positions were Korean (69 Japanese versus 24 Koreans). The only assignment outside the mines which had a majority of Korean laborers was outside mineral transportation (17 Japanese versus 49 Koreans). There was also a job category of “other” to which 321 Japanese and no Koreans were assigned. Hirose Teizō suggests this may refer to female mineral separators working outside the mines.[111] There was no category for farming.

Laborers were divided into three work shifts of officially 7-9 hours: 6am to 3pm, 2:30pm to 11pm, and 11pm to 6am.[112] However, a Niigata Shimbun journalist who experienced working in the Torigoe-tunnel of the Sado mines reported that the majority of miners had to work overtime, making each shift about 12 hours long.[113] The distance between dormitories and working stations could potentially add hours of walking and/or hiking to the daily schedule. In the month of July 1941, Sado mine laborers worked an average of 28 days.[114]

Mitsubishi’s record of job assignments for Korean and Japanese laborers in the Sado mines, June 1943.

Wages

In principle, wages of Korean forced laborers were equal to that of Japanese employees. This was not actually the case, however, due to skewed job assignments with varying wages and incentives, discriminatory deductions, and Korean wages being withheld during and after Japan’s defeat. Wages were calculated based on each laborer’s quotas varying by job assignments.[115] Regardless of wage levels, deductions were made for food and working gear including clothing and tools.[116] Deductions continued even during food shortages that forced Korean laborers to farm and pay for extra rice to supplement their miniscule rations.[117]

Calculations of average monthly wages for wartime Korean forced laborers in the Sado mines range from 67 to 84 Yen.[118] However, only a fraction of these wages were paid because discriminatory deductions were applied exclusively to Koreans. Sado City’s World Heritage promotional report states that “for the purpose of life improvement,” Korean laborers were “prohibited from wasting their money.”[119] In order to prevent Korean laborers from accumulating cash, parts of their wages were put into compulsory national saving schemes.[120] Parts of Korean wages were also sent to Korea, possibly to prevent escapes, sometimes ending up with colonial government agencies and other times reaching laborers’ relatives.[121]

At the end of the Asia-Pacific War in August 1945, Mitsubishi held a total of 231,059.56 yen in salaries and severance pay for 1,141 Korean forced laborers at the Sado mines, on average 203 yen per worker.[122]Rather than transferring these wages to the workers, in 1949 Mitsubishi deposited them with Niigata Prefecture. After ten years, these Korean funds passed to the Japanese government.[123] No outstanding salaries for Japanese laborers were deposited by Mitsubishi. The 1965 Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea stipulates that unpaid wartime salaries can no longer be requested by South Koreans. Japan is still legally required to pay forced laborers from today’s North Korea, but there is no evidence that Japan recognizes any such obligation or that it has provided the funds.

Escapes and Institutional Racism

The large number of Korean escapes (148 out of 1,005) from the Sado mines underlines their lack of freedom. There were also large numbers of strikes for reasons including lack of food and unpaid wages.[124] One of Mitsubishi’s wartime labor managers on Sado commented that strikes also occurred due to the “extreme racism” of some of the Japanese managers.[125] According to the records of Niigata prefecture, the Japanese managers did not hide their view of Koreans as racially inferior.[126] They said that strikes occurred because the “intelligence level of Koreans (知能程度)” was lower than first estimated, pointing out “a unique Korean deviousness (半島人特有の狡猾性)” and “tendency to blindly follow crowds without personal judgement (付和雷同性).”[127]

Mitsubishi did not improve the conditions of Korean forced laborers to reduce strikes and escapes. Instead, the company decided to strengthen ties with local police, reduce sympathy for Korean laborers and punish those who helped them escape.[128] When Koreans escapees were caught, they were sent to a police station for interrogation, sometimes fined, and returned to Mitsubishi.[129] According to Sakaue Torakichi, the Mitsubishi dormitory boss, policemen beating and kicking Korean laborers was common.[130]

Towards Liberation

In order to center all mining efforts on copper, which was needed in large amounts for weapons and munitions, the Japanese government closed all goldmines in the country that did not also produce copper from April 1943. In 1944 Mitsubishi produced 890 tons of copper compared with 531kg of gold.[131] As the shift to copper made the Sado mines’ labor force excessive, 408 Korean forced laborers were transferred to underground military construction sites in Saitama and Fukushima prefectures in 1945.[132]

When Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945, Korean forced laborers knew that they would soon be free. Mitsubishi’s Sado mine managers, however, held a meeting the next day with the Sado Aikawa chief of police to prevent the loss of Korean laborers.[133] Mitsubishi recorded another seven Korean escapes between August 15th and September 11th.[134] Korean laborers refused to continue mining, and Mitsubishi responded by blocking their access to food. At that point, some 40 Koreans broke into the main kitchen to secure food.[135] Korean forced laborers on Sado island were finally returned to Korea in the period from October to December 1945—the last returns from Niigata Prefecture.[136]

What is Forced Labor?

Japan often argues that because wartime Korean laborers received wages, they cannot be classified as forced laborers. This constitutes denial of the actual conditions and circumstances of wartime Korean labor.[137] Japan has a long history of various forms of slave labor. For example, prison laborers received wages even as they were required to pay for their own work equipment and sometimes for food. For example, Meiji Era prison laborers in the coalmines received wages equivalent on average to 25% of a contracted miner.[138] Koreans forced to work in the Sado mines during wartime were also waged, but they did not receive the amounts promised, nor could they spend their money freely. Wages were used as a means of control with payments deducted for their equipment and food. Most important, as documented earlier, Mitsubishi retained much of the wages they had earned and never transferred them to the laborers even after Japan’s surrender and their return to Korea. It is true that the system which allowed forced laborers to live with non-working family members is different from traditional chattel slavery, but it was still a system for forced labor. In order to feed and protect their families, forced laborers, like Im T’aeho, had to follow orders or risk their families’ safety by attempting dangerous escapes. The problem remains that the most influential historical narratives describing Japan’s industrial heritage sites have been constructed mostly by corporations and politicians, rather than historians.[139]

The International Labor Organization’s (ILO) Forced Labor Convention of 1930, ratified by Japan, defines forced labor as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily.”[140] Article 2 makes an exception for emergencies like war in which the labor is necessary not to “endanger the existence or the well-being of the whole or part of the population.” However, there was no legal basis for forcing hundreds of thousands of Koreans to work in Japan under abysmal conditions that condemned many to death. The ILO “considers that the massive conscription of labour to work for private industry in Japan under such deplorable conditions was a violation of the [1930 Forced Labor] Convention.”[141]

Systems of forced labor are not necessarily identical to those of chattel slavery. Koreans working in Mitsubishi’s Sado mines and elsewhere during wartime were abused as forced laborers under a discriminatory system organized and enforced by corporations such as Mitsubishi with support of the Japanese state. Recognition of the true character of this history would greatly elevate the universal value of the Sado mines as a UNESCO World Heritage site. They cannot be suppressed for the sake of instilling pride in future Japanese generations to the neglect of the victims.

Between Nomination and Inscription

“Sado is filled with every sort of story of people seeking gold. We want to tell their unwritten stories to the future. That is the ultimate goal of seeking World Heritage [inscription].”[142]

The above is a quote from June 2016 by Hamano Hiroshi, Sado City instructor of Niigata Prefecture’s World Heritage Promotion Section, from the prefecture’s official video about the modern history of the Sado mines. The narrator of the same video states that the “start of the Showa-era was to become the most prosperous period ever for Sado mine,” and that “the creativity and inventiveness of many people” lies behind the mines’ great success. Neither the war nor the plight of Korean laborers are mentioned. By contrast, in 1996 Sado Island tour guides described the Sado mines as “a hell of cold and damp where half-starved prisoners picked, shoveled, and clawed gold ore from the walls of freezing rock galleries until they shivered to death from pneumonia.”[143] Even the Edo period narratives of prison labor are now presented in the form of celebratory narratives of superior goldmining techniques.[144] It appears that as a potential World Heritage inscription draws nearer, more and more stories of “people seeking gold” are being censored and forgotten.

The Japanese government has implied that the Sado mines’ nomination will be limited to the Edo period.[145] The nomination, filed February 1st 2022, has not at this writing been made public. It is likely to state that the Outstanding Universal Value of the mines comes from Edo-period innovations and events. This way, Mitsubishi and its Korean forced laborers could be completely omitted from the narrative. UNESCO, however, did not accept Japan’s proposed limited historical range for the Meiji Industrial Sites, concluding that the full story should be told. The Sado mines nomination is likely to follow the same pattern.

For the Sado mines to become World Heritage in 2023, 14 out of 21 UNESCO World Heritage Committee member countries must support its inscription. Prior to the inscription of the Meiji Industrial Sites, Korean and Japanese representatives travelled around the world to convince committee member countries of their respective historical interpretations.[146] With the Sado nomination, Japan is again using UNESCO as an international battlefield for their “history war,” attempting to convince other countries to legitimize its benign interpretation of the history of the mine and Korean forced labor. Since the 2015 Meiji Industrial Sites’ World Heritage inscription, Japan has broken its promise to tell the stories of Korean victims. It similarly effectively blocked Korea’s registration of “Voices of the ‘Comfort Women’” in the UNESCO Memory of the World Program, insisting that victims of Japan’s military system of sexual slavery were professional prostitutes.[147] In terms of heritage politics, Japan has become a rogue nation. Japan’s “history war” has entered the global arena and threatens the spirit of UNESCO. UNESCO should not accept Japan’s World Heritage nomination for the Sado mines unless Japan pledges to provide forthright discussion of the plight of Korean victims in historical interpretation of the Meiji Industrial Sites and clearly recognizes the forced labor that took place in the Sado mines.

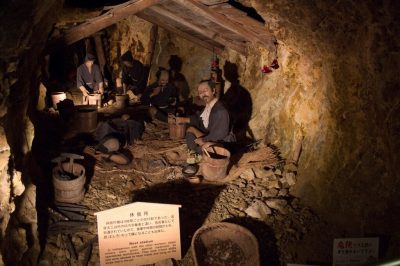

Inside a Sado mine tunnel with display mannequins. Photo by imp98 (CC), flickr, 2016.

Acknowledgements

Global travel disruptions in Covid times have prevented visits to Japan while preparing this article. Some of the cited sources have been obtained through membership in the Network for Research on Forced Labor Mobilization. I would like to express my thanks to David Palmer for his support including extensive advice on the presentation of arguments and detailed comments on earlier drafts; Mark Selden for copy-editing; Kobayashi Hisatomo for advice and for sharing sources; and Takeuchi Yasuto for sharing sources.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @globalresearch_crg and Twitter at @crglobalization. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums, etc.

Nikolai Johnsen is currently undertaking his Ph.D. in Korean and Japanese studies at SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies), University of London. His dissertation research is focused on how dark tourism trends visualises marginalised memories of colonialism in South Korea and Japan. An avid traveller, Nikolai has work experience leading tours to North Korea and Japan. He is the author of a two-part article on “Kato Joko’s Meiji Industrial Revolution – Forgetting forced labor to celebrate Japan’s World Heritage” in The Asia-Pacific Journal. Nikolai Johnsen can be contacted at [email protected]

Notes

1 Permanent Delegation of Japan to UNESCO, The Sado complex of heritage mines, primarily gold mines, 11 Nov. 2010; Nikkei staff writers, “Japan goes forward with Sado gold mine World Heritage bid”, Nikkei Asia, 28 Jan. 2022.

2 ANN News, “‘佐渡島の金山’世界遺産に推薦へ 方針一転の背景に安倍元総理か”(“‘Sadogashima no kinzan’ sekai isan ni suisen e – Hōshin itten no haikei ni Abe moto sōri ka”), 28 Jan. 2022; Abe Ryūtarō, “「どうするかなぁ」佐渡金山推薦 悩んだ首相が安倍氏に電話した理由” (“’Dō suru kanā’ Sado kinzan suisen – Nayanda shushō ga Abe shi ni denwa shita riyū”), Asahi Shimbun Digital, 29 Jan. 2022.

3 ANN News, “‘Sadogashima no kinzan.’”

4 NHK, “シブ5時 ”(“Jibu go-ji”) broadcast 27 January 2022. Search Twitter for #歴史戦チーム for the captured video.

5 Nikkei, “Japan goes forward”.

6 Uematsu Seiji, “佐渡金山の世界遺産推薦問題に「歴史戦」とやらの余地はない” (“Sado kinzan no sekai isan suisen mondai ni ‘rekishisen’ to yara no yochi wa nai”), Asahi Shimbun Digital – Ronza, 7 Feb. 2022. The books were 『佐渡鉱山史』 (大平鉱業佐渡鉱業所)and 佐渡鉱業所『半島労務管理ニ付テ』(“Sado kōzanshi” (Ōhira kōgyō sado kōgyōsho) and Sado kōgyōsho “Hantō rōmu kanri ni tsuite”). For details on these books, see Takeuchi Yasuto, “佐渡鉱山での朝鮮人強制労働 – 強制労働否定論批判”(“Sado kōzan de no Chōsenjin kyōsei rōdō – Kyōsei rōdō hiteiron hihan”), 4 Feb. 2022.

7 Takatori Shūichi, “歴史戦を闘い抜く”(“rekishisen wo tatakainuku”), personal blog, 20 Jan.

8 WHC.15 /39.COM /INF.19, Summary Records from the World Heritage Committee’s 39th Session, 28 June – 8 July 2015, pp 222.

9 Nikolai Johnsen, “Katō Kōko’s Meiji Industrial Revolution – Forgetting forced labor to celebrate Japan’s World Heritage Sites, Part 1”, The Asia Pacific Journal / Japan Focus, vol. 19, issue 23, no. 1, Dec. 1, 2021; Johnsen, “Katō Kōko’s Meiji Industrial Revolution…, Part 2”, vol. 19, issue 24, no. 5, Dec. 15, 2021.

10 For example Yi Chinyŏng, “[횡설수설/이진영]‘제2의 군함도’ 사도광산” (“[Hoengsŏlssusŏl/Yi Jinyŏng]‘Che 2 ŭi Kunhamdo’ Sadogwangsan”), The Dong-A Ilbo, 30 Dec. 2021; An Sangu, “정부, ‘제2의 군함도‘ 日 사도광산등재 시도 강력 항의”(Chŏngbu, ‘che 2 ŭi Kunhamdo’ Il sadogwangsan tŭngjae sido kangnyŏk hangŭi”), SBS News, 29 Dec. 2021.

11 Sado kankō kōryū kikō, 佐渡とは (Sado to wa), 22 Aug. 2018

12 Sado kankō kōryū kikō, 2020年度佐渡観光データ調査分析業務報告書 (2020 nendo Sado kankō dēta chōsa bunseki gyōmu hōkokusho), 29 March 2021.

13 UNESCO, Tentative Lists, n.d.

14 Niigata Prefucture and Sado City, 2006 application for registering Sado mines for Japan’s Tentative List; Niigata World Heritage registration promotion office and Sado City World Heritage Promotional Division, “佐渡金銀山の世界遺産登録を目指して”(“Sado kinginzan no sekai isan tōroku wo mezashite”), The World of Cultural Heritage, 13 Jan. 2016.

15 Tabiris, “「明治日本の産業革命遺産」世界遺産候補の政治的な決定は残念。 推薦決定過程の透明化を”(“Meiji Nippon no sangyō kakumei isan” sekai isan kōho no seiji tekina kettei wa zannen – Suisen kettei katei no tōmei ka wo”), 4 October 2013.

16 Niigata Prefectural government, “Modern Period – The Exquisite Isle – Sado Mine, Road to World Heritage”, YouTube, 24 June 2016.

17 Permanent Delegation of Japan to UNESCO, The Sado complex.

18 David Palmer, “Kishida’s Sado Mines Nomination: Leaving out Meiji industrialization, Mitsubishi, and Koreans”, Korea on Point, 14 Feb. 2022.

19 Fumio Yoshiki, “Metal Mining and Foreign Employees,” The Developing Economies (14), 1979.

20 Sado City, 佐渡相川の鉱山及び鉱山町の文化的景観 (Sado Aikawa no kōzan oyobi kōzan machi no bunka teki keikan). March 2020.

21 Sado Television, “鬼太鼓シリーズ 新穂青木(2021年4月15日)”(“Onidaiko shirīsu Niihoaoki (2021-nen 4-gatsu 15-nichi”), YouTube, 26 April 2021.

22 Tanaka Mitsuo, “炭鉱における囚人労働”(“ Tankō ni okeru shūjin rōdō”), Dai-ichi keizaidaigaku keizai kenkyūkai (3), 3 Jan. 1974 pp. 43-128.

23 ISM Publishing Lab, “どさ-くさ”(“Dosa-kusa”), Hanashi no neta ni Naru! Gogen Dai-jisho (digital) 2013.

24 Nakagawa Takao, “Pneumoconiosis recorded in 1840 at Aikawa Mine, Sado Island, Northeast Japan (Part 4)”, Nippon chishitsu gakkai dai-125-nen gakujutsu taikai (2018 Sapporo – Tsukubai), Sept. 2018.

25 Angus Waycott quoted this number in 1996 from a stone memorial located at the end of a footpath beginning about 200 yards below the main Aikawa mine entrance. See Angus Waycott, Sado: Japan’s Island in Exile (Berkeley: Stonebridge Press 1996), pp.63-64.

26 Yoshiki, “Metal Mining”; Sado City, Sado Aikawa no kōzan; Niigata Prefecture and Sado City, 再発見!!佐渡金銀山 (Saihakken!! Sado kinginzan), Sept. 2015.

27 Yoshiki, “Metal Mining”; Sado City, Sado Aikawa no kōzan.

28 Mitsubishi Materials, Sado Gold Mine.

29 Mark Metzler, Lever of Empire: The International Gold Standard and the Crisis of Liberalism in Prewar Japan(Berkeley & London: University of California Press, 2006) pp. 14-29.

30 Hirose, The Sado Mine.

31 Ibid.

32 Ōyama Shikitarō, “高島炭坑に見る明治前期の親方制度の実態 (“Takashima tankō ni miru meiji zenki no oyakata seido no jittai”), Ritsumeikan Keizaigaku 4 (2), 1955, pp. 178-221; Miura Toyohiko, “労働観私論 (VI) 20世紀初頭の日本の労働観” (“Rōdōkan shiron (VI) – 20-seiki shotō no nippon no rōdōkan”), Rōdō kagaku 70 (7), 1994, pp. 316-333.

33 Hirose, The Sado Mine.

34 Ibid pp. 4.

35 Specifically, Mitsubishi Materials Corporation, of the Mitsubishi Group. Mitsubishi Materials Corporation, previously Mitsubishi Mining, owned the Sado mines from 1918-1989. Hashima (“Battleship Island”) was also owned and operated by Mitsubishi Materials Corporation.

36 Hirose, The Sado Mine. Pp. 4-7; Niigata Prefecture and Sado City, Saihakken!!

37 Hirose, The Sado Mine.

38 Ibid.

39 Niigata Prefecture and Sado City, Saihakken!!

40 Golden Sado,コース概要 (Kōsu gaiyō), n.d.

41 Golden Sado, 株式会社 ゴールデン佐渡 会社案内 (Kabushikigaisha Gōruden Sado kaisha annai), 2015.

42 Johnsen, “Katō Kōko 1”; Johnsen, “Katō Kōko 2”.

43 Chōsenjin kyōsei renkō shinsō chōsa-dan, “佐渡鉱山へ連行されて 林泰鍋”( Sado kōzan he renkō sarete – Rimu Teho), Chōsenjin kyōsei renkō no kiroku – Kantō-hen (Tokyo: Kashiwa Shobō, 2002) pp. 301-302.

44 Ch’oe Ŭn’gyŏng, “日 사도광산 가치 인정받고 싶다면 역사 왜곡 멈춰야” (“Il Sadogwangsan kach’i injŏngbatko sip’tamyŏn yŏksa waegok mŏmch’wŏya”), Chosun Ilbo, 20 Jan. 2022; Ko Hyŏnsŭng, “사도광산 유족 ‘강제동원뺀 유네스코 등재는 거짓’” (“Sadogwangsan yujok ‘kangjedongwŏn” ppaen yunesŭk’o tŭngjaenŭn kŏjit’”), MBC News, 6 Jan. 2022; Ko Hyŏnsŭng, “‘살아서 나갈 수 있을까’ 사도광산의 참혹한 기록” (“‘sarasŏ nagal su issŭlkka’ Sadogwangsanŭi ch’amhokhan kirok”), MBC News, 30 Dec. 2021.

45 Year of escape unclear.

46 American Lung Association, Learn About Silicosis, 23 March 2020.

47 Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “일본지역 탄광 · 광산 조선인 강제동원 실태 –미쓰비시 (三菱) 광업 (주) 사도(佐渡) 광산을 중심으로” (“Ilbonjiyŏk t’an’gwang · kwangsan Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn silt’ae -missŭbisi kwangŏp (chu) Sado kwangsanŭl chungsimŭro”), The Foundation for Victims of Forced Mobilization by Imperial Japan, Dec. 2019.

48 Ibid, pp. 9-10.

49 Hirose, The Sado Mine.

50 Gregory Hadley and James Oglethorpe, “MacKay’s Betrayal: Solving the Mystery of the ‘Sado Island Prisoner-of-War Massacre’, The Journal of Military History 71(2), April 2007, pp. 441-464.

51 Niigata Prefecture, 新潟県史 通史編8 (Niigata kenshi – Tsūshi-hen 8), 1988, pp.772-786; Aikawa-machi-shi hensan iinkai, 佐渡相川の歴史 通史編 近・現代 (Sado Aikawa no rekishi – Tsūshihen – Kin/ Gendai), 1995.

52 See for example Takeuchi Yasuto, 調査・朝鮮人強制労働2 財閥・鉱山編 (Chōsa – Chōsenjin kyōsei rōdō 2 – Zaibatsu/ kōzan-hen), (Tokyo: Shakai hyōronsha, 2014); Nagasaki zainichi Chōsenjin no jinken wo mamoru kai, 軍艦島に耳をすませば・端島に強制連行された朝鮮人・中国人の記録 (Gunkanjima ni mimi wo sumaseba: Hashima ni kyōsei renkōsareta Chōsenjin Chūgokuin no kiroku), (Tokyo: Shakai Hyōronsha, 2016); Tonomura Masaru, 朝鮮人強制連行 (Chōsenjin kyōsei renkō), (Tokyo: Iwanami shinsho, 2012).

53 Niigata Prefecture, Niigata kenshi…8, pp. 773.

54 Hirose, The Sado Mine, pp 3-4.

55 Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”.

56 Yomiuri Shimbun, “信濃川を頻々流れ下がる鮮人の虐殺死體” (“Shinanogawa wo hinpin nagare sagaru senjin no gyakusatsu shitai”), 29 July 1922 pp. 5.

57 Michael Weiner, The Origins of the Korean Community in Japan, 1910-1923, Manchester University Press, 1989) pp 104-105.

58 Ibid.

59 Niigata Prefecture, Niigata kenshi…8, pp. 772-76.

60 Ibid; Niigata Prefecture, Niigata kenshi…8, pp. 776-78.

61 Niigata Prefecture, Niigata kenshi…8, pp. 776.

62 Sado City World Heritage Promotional Division, 佐渡相川の鉱山都市景観保存調査報告書 (Sado Aikawa no kōzan toshi keikan hozon chōsa hōkokusho), pp.68-69.

63 See for example Tonomura, Chōsenjin kyōsei renkō.

64 Aikawa-machi-shi hensan iinkai, 佐渡相川の歴史 通史編 近・現代 (Sado Aikawa no rekishi – Tsūshihen – Kin/ Gendai), 1995, pp. 680, as cited by Hirose, The Sado Mine, pp. 7 and Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 105

65 Hirose, The Sado Mine, pp. 13. It is not clear whether the name list included deaths from before the Taishō-era.

66 Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 96.

67 See for example Takeuchi Yasuto, 明治日本の産業革命遺産・強制労働Q&A (Meiji Nippon no sangyō kakumei isan / kyōsei rōdō Q&A), (Tokyo: Shakai Hyōronsha, 2018), pp18-20.

68 Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 98; 104.

69 Ibid, pp. 104.

70 Sado City, Sado Aikawa no kōzan, pp.68-69.

71 See for example Tonomura, Chōsenjin kyōsei renkō; Johnsen, “Katō Kōko 1”

72 Niigata Prefecture, Niigata kenshi…8, pp. 782.

73 David Palmer, “Foreign Forced Labor at Mitsubishi’s Nagasaki and Hiroshima Shipyards: Big Business, Militarized Government, and the Absence of Shipbuilding Workers’ Rights in World War II,” in Marcel van der Linden and Magaly Rodríguez García, eds, On Coerced Labor: Work and Compulsion after Chattel Slavery (Leiden: Brill, 2016), pp. 169-77.

74 Hirose, The Sado Mine, pp. 12.

75 Ibid; Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 111.

76 Niigata Prefecture, Niigata kenshi…8, pp. 783-85.

77 Hirose, The Sado Mine, pp. 13

78 Ibid pp. 11.

79 Seokwoo Lee and Seryon Lee, “Yeo Woon Taek v. New Nippon Steel Corporation,” American Journal of International Law 113 (3), 11 July 2019, pp. 592-599.

80 Takeuchi, Q&A pp. 18-9; Takeuchi, Zaibatsu/ kōzan-hen pp. 15-18

81 Takeuchi, Q&A pp. 86

82 Ibid, pp. 85.

83 Ibid, pp. 85.

84 Hirose, The Sado Mine, pp. 1

85 Takeuchi, “Sado kōzan.

86 Sado kōgyōsho (Mitsubishi Materials), 半島労務管理ニ付テ(“Hantō rōmu kanri ni tsuite”). (Sado, 1943), copy from Zainichi Chōsenjin rekishi kenkyū 32-gō shoshū, pp. 432-448.

87 Sado kōgyōsho, Hantō rōmu, pp. 439; 440.

88 Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 104.

89 Takeuchi, “Sado kōzan.

90 Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 71.

91 Sado kōgyōsho, Hantō rōmu, pp. 439

92 Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn” pp. 98-99.

93 Ibid, pp. 107.

94 Ibid, pp. 107; Hirose, The Sado Mine, pp. 15

95 Sado City, Sado Aikawa no kōzan, pp.68-69.

96 Isono Tamotsu, “[にいがた人模様]強制連行された朝鮮人を語る・坂上寅吉さん” (“Niigata hitomoyō – Kyōsei renkō sareta Chōsenjin wo kataru Sakaue Torakichi-san”), Mainichi Shimbun Niigata edition, 24 Feb. 2002 pp.23

97 Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 108.

98 Hirose, The Sado Mine,pp. 15

99 Ibid, pp. 14

100 Cited by Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp 108; Hirose, The Sado Mine, pp. 15.

101 Hirose, The Sado Mine,pp.15

102 Ibid, pp. 10

103 Ibid

104 Ibid

105 Sado City, Sado Aikawa no kōzan, pp.68-69.

106 Sado kōgyōsho, Hantō rōmu, pp. 440.

107 Niigata Shimbun, “佐渡鑛山夫の事故減少” (“Sado Kōzanbu no jiko genshō”), 9 July 1935, as cited by Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 104.

108 Niigata Prefecture, Niigata kenshi…8, pp. 785

109 Hirose, The Sado Mine,pp.10

110 Sado kōgyōsho, Hantō rōmu, pp. 440.

111 Hirose, The Sado Mine,pp.10

112 Sado City, Sado Aikawa no kōzan, pp.68-69.

113 Niigata Shimbun, “現地報告12” (“Genchi hōkoku 12”), 22 August 1943, as cited by Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn” pp. 100.

114 Sado City, Sado Aikawa no kōzan, pp.68-69.

115 Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 101.

116 Ibid, pp. 101; 111; Hirose, The Sado Mine,pp. 13-14; Sado City, Sado Aikawa no kōzan, pp.68-69.

117 Sado City, Sado Aikawa no kōzan, pp.68-69.

118 Ibid; Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 101.

119 Sado City, Sado Aikawa no kōzan, pp.68-69.

120 Ibid.

121 Hirose, The Sado Mine,pp.16

122 Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 74-76

123 E-mail correspondence with Kobayashi Hisatomo of the Network for Research on Forced Labor Mobilization on February 18th 2022; Official written response by Niigata Prefecture to Kobayashi Hisatomo dated 6 Dec. 2021.

124 Hirose, The Sado Mine,pp.13-15; Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 111

125 Aikawa-machi-shi hensan iinkai, Sado Aikawa no rekishi, as cited by Uematsu Seiji, “Sado kinzan”

126 Niigata Prefecture, Niigata kenshi…8, pp. 783.

127 Ibid.

128 Hirose, The Sado Mine,pp.15.

129 Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 112.

130 Isono, “Sakaue Torakichi-san”.

131 Hirose, The Sado Mine,pp.6; Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 89.

132 Sado City, Sado Aikawa no kōzan, pp.68-69. Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 105.

133 Hirose, The Sado Mine pp. 20.

134 Ibid.

135 Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 113.

136 Hirose, The Sado Mine, pp. 22.

137 Chŏng Hyekyŏng, “Chosŏnin kangjedongwŏn”, pp. 103

138 Tanaka, “Tankō”, pp. 47.

139 Johnsen, “Katō Kōko 1”; Johnsen, “Katō Kōko 2”.

140 International Labour Organization, Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29), pp. 1.

141 ILO, Observation (CEACR) – adopted 1998, published 87th ILC session (1999).

142 Niigata Prefectural government, “Modern Period”.

143 Waycott, Sado, pp. 63.

144 Permanent Delegation of Japan to UNESCO, The Sado complex.

145 Asahi Shimbun Digital, “佐渡金山の世界文化遺産登録、政府が一転推薦へ 韓国は反発か” (“Sado kinzan no sekai bunka isan tōroku, seifu ga itten suisen he – Kankoku wa hanpatsu ka”), 28 Jan. 2021.

146 Johnsen, “Katō Kōko 1”; Johnsen, “Katō Kōko 2”.

147 Heisoo Shin, “Voices of the ‘Comfort Women’: The Power Politics Surrounding the UNESCO Documentary Heritage”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 19, 5, 8, 1 March 2021