Tectonic Shock in India-Russia Relationship

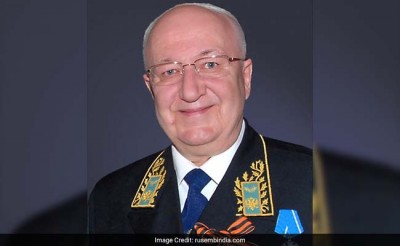

The Death of Russia's Ambassador Alexander Kadakin

The surprise passing of one of Russia’s most distinguished and influential diplomats, His Excellency Mr. Alexander Kadakin, has come as a tragic shock for Moscow and New Delhi. No single individual has been more important in promoting and strengthening the Russian-Indian Strategic Partnership than Ambassador Kadakin, and his irreplaceable contribution to the emerging Multipolar World Order will be dearly missed.

He served during a time of paradigmatic geopolitical changes, whereby Russia reemerged from its post-Soviet slumber as one of the leading multipolar Great Powers in the world concurrent with traditionally “Non-Aligned” India (which is nevertheless a misleading Cold War-era myth) rapidly moving in the direction of clinching an unprecedented military-strategic partnership with the US.

Despite the obvious divergences in Moscow and New Delhi’s geopolitical priorities, the two sides have hitherto managed to retain their historical bonds of friendship and their relationship has seemingly managed to avoid being negatively impacted by these developments, and that’s all thanks to the diplomatic expertise and professionalism of Ambassador Kadakin. Nevertheless, cracks had already begun to surface before his passing, and these are evidenced most clearly through the increasingly aggressive tone of the Indian media when discussing Russia’s rapprochement with Pakistan.

The author explored the uncomfortable nuances of Russian-Indian relations in a series of articles listed as part of his 2017 forecast for South Asia for the Moscow-based Katehon think tank, and the reader is strongly encouraged to review these materials in-depth to learn more about how the joint US-Indian Hybrid War on CPEC is dangerously threatening India’s traditional ties with Russia and fulfilling a grand American plan to turn New Delhi into Washington’s premier mainland proxy in Eurasia.

Russia couldn’t avoid noticing this startling game-changing development, yet it opted to redouble its efforts to strengthen its strategic partnership with India in order to make a play for its geopolitical loyalty. This is in line with what the author suggested last May in his Katehon series about “The Meaning Of Multipolarity”, the two most relevant articles of which advised that Russia not give up on its historically and instead make a determined bid to either keep it in the multipolar community or at the very least delay its ‘defection’ to the unipolar one.

Ambassador Kadakin was instrumental in this policy, but other influential diplomats in Moscow felt that he might have been going a bit too far in his approach by overly indulging India’s diplomatic interests in the region at the expense of Russia’s rapprochement with Pakistan. Mr. Zamir Kabulov, Russia’s envoy to Afghanistan and a rising force in guiding Moscow’s South Asian strategy, recently emerged as a counterweight to Ambassador Kadakin, and the author wrote about their visibly contradictory geopolitical visions in his Katehon article asking “Is Russia’s ‘Deep State’ Divided Over India?”

The research revealed that Kabulov is an “Islamophile” who believes that Russia’s South Asian strategy shouldn’t be Indo-centric, while Kadakin is an “Indophile” who thinks that Moscow’s regional policies should depend on its ties with New Delhi first and foremost. Up until Ambassador Kadakin’s passing, these two forces maintained equilibrium in determining the Kremlin’s policy towards Pakistan and India, which explains why Russia has so far been able to expertly balance its Pakistani rapprochement with its traditional Indian relationship.

Following the death of this remarkable Ambassador, however, it’s going to be very difficult for Russia to replace him with anyone as distinguished, capable, and trusted by the Indian establishment as Kadakin was. It’s not to say that Russia doesn’t have excellent diplomats, but just that Ambassador Kadakin was truly one of a kind and irreplaceable in his own way. Giants such as him always leave a void in their passing, and just as it was with the late Ambassador to Turkey Andrei Karlov, so too will it be with the late Ambassador to India Alexander Kadakin.

It can be expected that the diplomatic transition from Kadakin to his successor will be smooth and fully supported by his Indian hosts, but that the influence which the “Indophiles” wield in Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs will never be the same again. The balance between them and Kabulov’s “Islamophiles” has suddenly shifted in favor of the latter, and this may lead to changes in Russia’s South Asian strategy.

In practical terms, while Moscow will likely continue to pursue its incipient balancing act between New Delhi and Islamabad, Modi’s government might try to take advantage of the new Russian Ambassador by aggressively pressuring him to halt his country’s rapprochement with Pakistan. It’s not predicted that Russia will alter its current strategy and appease India, though, because it both appreciates the trans-regional benefits of its Pakistani rapprochement policy in South-Central Asia (Afghanistan and CPEC) and is now decisively much more under the sway of the “Islamophiles” than the “Indophiles”.

This failure to comply with India’s unilateral demands could incense Modi and his influential National Security Advisor Ajit Doval, who might be convinced that this is the last opportunity to stop Russia’s rapprochement with Pakistan. Given the predominant weight that the US is presently exerting on Indian foreign policy at the moment, it’s forecast that Washington will exploit the enraged Indian leaders in order to encourage them to more visibly ‘break’ from Moscow in response.

This wouldn’t happen openly on a state-to-state level, of course, but in symbolic ways such as through the media and “expert” communities meant to convey the undeniable message of New Delhi’s supreme displeasure with Moscow and its willingness to more closely embrace Washington if it can’t get what it wants from Russia. This wouldn’t be anything new, however, but rather a reinforcement of the current ‘triangular’ diplomacy of “multi-alignment” that India’s recently involved itself in.

The key difference, however, is that India would be less inclined to work with a Pakistan-friendly Putin than an anti-Pakistan Trump, and it might accordingly accelerate its unprecedented military-strategic partnership with the US in order to capitalize off of this opportune moment. India and the US have been waiting for a convenient pretext to do this anyhow, and the passing of Ambassador Kadakin and his successor’s refusal of New Delhi’s expected ‘ultimatum’ that Moscow cut off its newfound pragmatic relations with Islamabad might be just what Modi-Doval need in order to more fully ‘legitimize’ their pro-American pivot.

Russia, for its part, while sincerely wanting to retain its treasured relations with India, might eventually end up losing its enthusiasm if the obvious reversal in India’s foreign policy priorities humiliatingly becomes apparent, and it could be influenced by the “Islamophiles” to transfer this passion to Pakistan instead. The result of this process would be that India and Russia continue to drift apart, just as the US intends for them to do, with Moscow unable to reverse this development after suddenly losing Ambassador Kadakin.

It’s very possible that President Putin might contemplate visiting South Asia much more seriously now than before, understanding that his presence there is needed much more than ever in order to safeguard and promote Russian interests. This prospective trip wouldn’t be just to reinforce Russia’s newfound balancing policy in the region, but to reinforce the Russian-Indian Strategic Partnership during this unexpected period of uncertainty.

With Kabulov’s “Islamophiles” more comfortably in control of Russia’s South Asian strategy and the former “deep state” equilibrium with the “Indophiles” suddenly broken, the paranoid Hindutva jingoists at the head of India’s government might fret that any accelerated rapprochement between Moscow and Islamabad will be at New Delhi’s expense. This is illogical for any level-headed person to believe, however, and Kabulov himself aptly said in December at the Heart of Asia conference that “India has close cooperation with the US, does Moscow complain? Then why complain about much lower level of cooperation with Pakistan?”

Regardless of Russia’s reasonable retort to New Delhi’s unfounded fears, Modi-Doval don’t interpret the situation like Kabulov expressed it, and instead believe that Russia is conspiring against them as part of a secret Chinese plot, like some Indian “experts” have repeatedly hinted at over the past couple of months. This fuels their desire to more rapidly and openly move towards the US, though not without giving Russia one final ‘ultimatum’ beforehand, which could be conveyed either discretely to Ambassador Kadakin’s successor or directly to President Putin during any forthcoming prospective visit to South Asia.

No matter what ultimately happens, though, it’s clear that Ambassador Kadakin’s passing decisively shifted the “deep state” balance between Russia’s “Islamophiles” and “Indophiles”, and that this will inevitably have consequences on the present state of affairs in the region. India senses its last-ever potential opportunity to reverse Russia’s rapprochement with Pakistan, while Russia contrarily sees a chance to take the latter in an excitingly new direction unburdened by the overly cautious approach which characterized Ambassador Kadakin’s “Indophile” influence.

Given these diverging dynamics, one can easily expect that the US’ efforts to drive a deeper wedge between Russia and India will assuredly lead to some sort of fruitful dividends in the coming future, with the only question being the extent to which American efforts will succeed in more openly convincing India to side with the US and against Russia in the New Cold War. More than likely, New Delhi won’t ever publicly turn against Moscow unless it becomes overly paranoid about Russia’s relations with Pakistan, so it can be assumed that this process will play out gradually and be largely kept out of the public eye (except for the symbolic manifestations mentioned earlier pertaining to India’s media and “expert” communities).

It’ll be a profound challenge for Russia to reverse or at least slow down India’s ‘defection’ to the US now that it can no longer rely on the remarkable diplomatic skills of Ambassador Kadakin, so Moscow might finally become comfortable with what’s increasingly appearing to be an irreversible geopolitical fact and concentrate more closely instead on preserving the mutually beneficial military-energy aspects of its fading strategic partnership with India while simultaneously exploring ‘compensational’ opportunities with Pakistan.