Forced Labour in Imperial Japan’s First Colony: Hokkaidō

Introduction1

Japanese empire-building relied heavily on the use of forced labour by politically marginalized – subaltern – people. It is well-known that prisoners across Japan have contributed to large-scale projects like the Miike coal mines2 and road-building in Hokkaidō.3 This article contributes to existing research on the relationship between forced labour and the building of modern Japan. It focuses on Hokkaidō and highlights how, from its onset in the 18th century, the management of “Imperial Japan’s first colony”4relied on exploiting the labour of politically marginalized, subaltern groups, such as the indigenous Ainu and convicts in forced labour camps (ninsoku yoseba). Colonial studies of the Japanese Empire have long neglected the Hokkaidō’s colonial status5. Hokkaidō’s own local history activism and Western scholarship argue that Japanese imperialism started well before 1895 (annexation of Taiwan). For instance, Tessa Morris-Suzuki’s work proves how “Tokugawa colonialism” exercised control over Ezo, i.e. Ainu land, long before the Meiji state’s formal colonization of these territories6. This research notwithstanding, the popular understanding of Hokkaidō’s Meiji history still gives the impression that from 1868 onwards Japanese settlers engaged in the clearance of empty land. These activities are typically described as kaitaku (colonization or land development) instead of shokuminchika (colonization). However, several authors have argued that the term kaitaku is a euphemism that covers the colonization of Ainu land:

Prevailing national narratives weave Hokkaido’s complex and fraught history into a seamless tale of Japan’s modernization and favours a lexicon of development (kaitaku) and progress (shinpō) over colonization and conquest”7

During the Meiji colonization of Hokkaidō political convicts in central prisons (shūjikan), indentured labourers (tako), as well as workers from colonial Korea, were assigned hazardous work such as road-building and coal mining.

Postcolonial studies pay particular attention to the experiences of the subaltern. Antonio Gramsci described the “subaltern” or “low rank” as persons or groups of people who experience hegemonic domination by a ruling class, one that denies them participation in the making of local history and culture as active individuals. In his Prison Notebooks, he writes:

the historical unity of the ruling classes is realised in the State, and their history is essentially the history of States and of groups of States (…) The subaltern classes, by definition, are not unified and cannot unite until they are able to become a “State”: their history, therefore, is intertwined with that of civil society, and thereby with the history of States and groups of States.8

This definition of the subaltern became a useful conceptual tool for groups like indigenous people, poor immigrants, or prisoners – the “losers” of empire- or state-building processes. Importantly, as the definition points out, diverse subaltern groups are not united amongst themselves. They may, as in Hokkaidō, come from different ethnic, political, national, or economic backgrounds, belong to different generations, or have different gendered or racial identities. Yet, all these men, women, and children share the experience of being politically marginalized and economically exploited by a dominant ruling class. In the absence of sufficient unity, the subaltern cannot, in fact, speak for “themselves.”9 And indeed, Shigematsu Kazuyoshi noted a general scarcity of sources on ninsoku yoseba in Ezo/Hokkaidō. In my own research on prisons and forced labour during Ezo’s colonization, I struggled to find personal accounts by prisoners. Likewise, the editors of Waga Yūbari, Shirarezaru yama no rekishi, a volume on the history of Hokkaidō’s Yūbari mine, mention that although there are records about the development of the coal mining industry, there are virtually no records about the actual living conditions of the coal miners themselves.10 The scarcity of existing primary sources produced by these subaltern workers highlights how their lives were literally regarded as disposable and irrelevant to dominant historiography. It is only since the late 1970s that Japanese grass-root activists started to “unearth” the history of these people, and thus to correct the historiography of Hokkaidō’s colonization.11

Ezo/Hokkaidō and Japanese Empire-Building

Although the formal colonization process of Hokkaidō began in 1869, Ezo played such an important role during the early formation of the Japanese state that the Japanese historian Takahashi Tomio writes: “The history of Ezo’s management is the history of state formation” (Ezo keiei-shi wa kokka seiritsu-shi dearu).12Indeed, during the formation of the Yamato state in the 4th and 5th Centuries, Japanese authorities were already concerned about the management of areas in the northeast. The peoples who inhabited these areas were referred to as “Emishi.” Importantly, Emishi was not an ethnic or racial category. Instead, the term referred to “crude and unrefined people,” who resisted Yamato control, and who opposed the socio-cultural and political-economic practices of the Japanese elite.13 In the 8th and 9th Centuries, the Heian court’s expansion into the north led to armed clashes with the Emishi, and from the 11th Century onwards, the Emishi were increasingly pushed back to the northernmost tip of Honshu, Hokkaidō, the southern part of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands. It was also during this time that the Japanese bureaucracy began referring to Emishi as Ezogashima, which can be translated as “barbarian islands.” The term Ezo, in turn, is an abbreviation of Ezogashima.14 In 1604, a year after Japan’s unification under Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1603, the Matsumae family in southern Ezo was granted exclusive rights to trade with the Ainu.

Exploitation of Ainu Labour

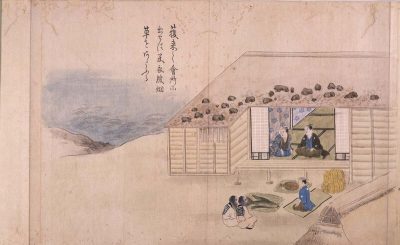

The Matsumae han established a trade system (basho seido), under which the Ainu adults and children became contractors and workers for Japanese traders. Trade with the Ainu revolved around exploitation across fishing grounds (see figure 1)

Figure 1: Hand scroll depicting trade between Ainu and Japanese. Literally translated, the inscription says:” When [the Ainu] come to the domain office and give a catch [of fish], [the Japanese traders] give rice, clothes and tobacco [in exchange]”. Source: Ezoshina kikan (蝦夷島奇観) 1799 by Hata Awagimaro © Tokyo National Museum.

This system continually evolved and reached its peak by the 19th century. Ainu writer Kayano Shigeru describes how in 1858, his grandfather, a boy from Niputani (present-day Nibutani), had to work as a slave under the basho seido. The village head, Inisetet, had tried in vain to prevent Japanese samurai from taking the young boy away: “Inisetet appealed to the samurai to leave the boy, only eleven years old and small for his age, saying that he would only be in their way if they took him along. The Japanese rejected Inisetet’s supplication, however, stating that even a child was capable of carrying one salmon on his back.”15

The exploitation of labour in Ezo also went hand in hand with the development of prostitution. During the fishing season, Japanese sex workers would solicit Ainu men at the ports of Wajin-chi (i.e. the Japanese settlements across the Oshima peninsula), while in the island’s interior, Japanese men engaged Ainu prostitutes and/or violated married Ainu women. For example, in 1793, Kimura Kenji, a writer from the Mito domain, noted that Japanese sailors who travelled to Ezo often committed acts of rape against married Ainu women. These women’s husbands would then visit the sailors’ ships to ask for some form of compensation, which was usually no more than a handful of tobacco. In the 1850s, the Japanese explorer Matsuura Takeshirō mentioned how a young Ainu woman in the Ishikari region had contracted syphilis after intercourse with a fishery supervisor. The supervisor had sent the woman’s husband away first to work in a fishery in Otarunai, before advancing on his wife. Matsuura also observed how out of the forty-one Japanese supervisors in Kusuri (present-day Kushiro), thirty-six men had forced Ainu women to serve as concubines, also after having sent their husbands away to work at fisheries elsewhere.16

Racism also thrived in Ezo, as many Japanese settlers regarded the Ainu as inhuman and the inferior descendants of dogs.17 Indeed, the Tokugawa view on the Ainu alternated between emphasizing their barbarian differences, to denying their otherness through forced assimilation projects. For example, in the late 18th and early 19th Centuries, the bakufu introduced measures to assimilate the Ainu community on Etorofu, one of the southern Kuril Islands, between the Russian Empire and Ezo. The measures were in response to the perceived threat from Russia in light of the Laxman expedition (1793) and the Rezanov mission’s violent intrusion (1804). Once this fear of Russia had abated, the shogunate abandoned any assimilation attempts until 1855, the year that the Treaty of Shimoda was signed, defining the border between Tokugawa Japan and the Russian Empire, between the two Kuril Islands Iturup and Urup. The bakufu thus perceived a new Russian threat to Japanese sovereignty over Ezo and assumed direct control of the island. Moreover, in order to secure Japanese territorial rights in areas predominantly inhabited by the Ainu (such as the Kuril Islands and southern Sakhalin), the shogunate imposed an assimilation programme on the Ainu once again.18

Forced Ainu labour continued to play a role during the Meiji period, when Ezo was annexed into Japanese territory under on-going colonial practices. In 1869, Ezo was renamed Hokkaidō and came under the jurisdiction of the so-called Hokkaidō Kaitaku-shi (Hokkaidō Development Office). James Ketelaar explained how only six months into 1869 – that is, two months before the establishment of the Kaitaku-shi – the Buddhist temple Higashi Honganji requested the Dajōkan’s (Council of State) permission to contribute to this colonization. Specifically, Higashi Honganji had three aims: first, to construct new roads throughout the interior of Hokkaidō; second, to recruit new immigrants from other parts of Japan for agricultural settlements in Ezo; and third, to conduct missionary work among these new immigrants, as well as among the local indigenous Ainu population. According to Ketelaar, the idea of Higashi Honganji assisting with Hokkaidō’s colonization originated from within the imperial court itself, where Yamashina no Miya Prince Hikaru told his brother-in-law Gonnyō, the head of the Higashi Honganji sect, that offering to help colonize Hokkaidō might improve the sect’s relations with the new Meiji government. Such a development was critical, given the government’s general anti-Buddhist stance. Moreover, Higashi Honganji, in particular, had been known for its long-standing loyalty to the Tokugawa bakufu. Gennyō’s son Kennyō was then sent to Hokkaidō, accompanied by a group of devotees, including engineers. After the party’s arrival in 1870, the engineers immediately began working to improve existing highways and build new ones.

Figure 2: The opening of a new highway in Hokkaidō through the temple named Higashi Honganji. Ainu workers are depicted wearing beards and yellow clothes decorated with geometrical patterns. Source: Hokkaidō shindō sekkai (北海道新道切開) 1871 © National Diet Library.

The longest of these roads connected Date with what was then the village of Satsuporo (later Sapporo). The 5000 people who worked on this 103 km long road project included prisoners sent to serve their sentences in Hokkaidō, as well as Ainu who were forced to work there. The Buddhist temple’s management of this forced Ainu labour exacerbated the already difficult relations between the Ainu and Japanese settlers. Unsurprisingly, these tensions severely complicated Higashi Honganji’s plans for Buddhist missionary activities among the Ainu population.19

In 1875, after Sakhalin had become Russian territory, 841 Ainu from the island were forcibly displaced and relocated to Cape Sōya at Hokkaidō’s northernmost point. From there, they were sent to the Ishikari River plain, where Kuroda Kiyotaka, the head of the Kaitaku-shi, tried to force them to work in the nearby Horonai coal mines. Apparently, this provoked protest from Matsumoto Jūrō, a judge who perceived similarities between the proposed work in the coal mines and the conditions in penal colonies like Sado Island. Although the Ainu were ultimately spared from working in these mines, they were nevertheless obliged to take up agricultural labour in the Ishikari basin. Judge Matsumoto again protested, but in vain, a development that eventually led to his resignation from office.20 The new lifestyle changes caused many of the displaced Sakhalin Ainu to suffer and die of cholera. By encouraging immigration from other parts of Japan, the Meiji government also ensured a labour force for its colonial project in Hokkaidō, independent of the Ainu. Thus, whereas Tokugawa colonization of Ezo had depended on Ainu labour, the Meiji colonial project rendered the Ainu largely “dispensable.”21

Convict Labour

The Treaty of Kanagawa (1854) and the Treaty of Shimoda (1855) both changed Japan’s foreign relations and had a particularly strong impact on Ezo. First, the Treaty of Kanagawa with Commodore Matthew C. Perry resulted in the opening of the port of Hakodate. Second, the Treaty of Shimoda with Russia defined the border between Tokugawa Japan and the Russian Empire. This formal proximity to the Russian Empire led to Japanese ideas of Hakodate being the “lock of the northern gate” (kitamon sayaku). Consequently, the Tokugawa bakufu thought it necessary to strengthen its positions in Ezo by sending more troops there. Moreover, it assumed direct control of some small Japanese fishing outposts on Sakhalin and promoted the island as a bountiful place.22 During this period, convicts from Hakodate were already working in the coal mines of Shiranuku and Kayanuma, providing coal for foreign ships that arrived there after the port’s opening. Ezo’s first ninsoku yoseba (forced labour camp) was then established in 1861 in Usubetsu, located in the south-central part of the island. This yoseba also had a branch office on Okushiri Island at Ezo’s western coast. Convict labour involved both men and women, but it seems that in Ezo, men and women had different tasks in the fishing industry.23 In 1865, the Usubetsu yoseba was closed and most inmates were transferred to Okushiri island, though the Okushiri yoseba was eventually closed in 1870, too, after the Battle of Hakodate (1869) disrupted the shipments of rice supplies. That same year, the Kaitaku-shi granted all 24 inmates the privilege of being pardoned from banishment to a distant island.24

Even so, Meiji colonization of Hokkaidō quickly resumed its reliance on prison labour. Indeed, because immigrant labour was not advancing Hokkaidō’s initial colonization as much as originally intended, in a letter dated 17 September 1879, Interior Minister Itō Hirobumi suggested the establishment of three central prisons (shūjikan) on Hokkaidō to accelerate the colonization process. These three prisons were especially designed to accommodate the rising numbers of political convicts, specifically after a series of uprisings among former samurai in the mid-1870s.25 In 1877, armed opposition culminated in the Satsuma Rebellion: 43,000 individuals were arrested, with 27,000 sentenced to detention and forced labour.26 By rendering Hokkaidō a prison island, it became possible to send political convicts to the outermost periphery, far away from the political troubles in Kyūshū. Once in Hokkaidō, prisoners were ordered to work for the island’s “development” and advance the colonial project, especially through agriculture and mining work. The political prisoners sent to Kabato, Sorachi and Kushiro prisons were mostly members of the Freedom and Peoples’ Rights Movement (Jiyū minken undo), a political movement that, between 1882 and 1884, opposed the Meiji government by instigating a series of violent uprisings.27 The rising numbers of supporters arrested from the movement were sent to the three central prisons in Hokkaidō.28

The first central prison was Kabato Prison, established in 1881 in Shibetsuputo, located in today’s Sorachi sub-prefecture. However, during the prison’s opening ceremony, the Ainu name “Shibetsuputo” was replaced with the Japanese name “Tsukigata,” from the first prison director, Tsukigata Kiyoshi. Of course, the name change not only honoured an individual, but also, and more importantly, served to “Japanize” Ezo/Hokkaidō’s geography.29 In 1882, a second central prison opened in the village of Ishikishiri (present-day Mikasa), near the Horonai coal mines, where, as mentioned above, Governor Kuroda Kiyotaka sought to force Ainu people to work.

From 1883 onwards, Sorachi prisoners also began working in the Horonai coal mines.30 As the pace of coal mining increased, Horonai became Japan’s third most productive coal mine, after Miike and Takashima. The Mitsui company was its largest buyer, exporting the coal to Singapore and Hong Kong. The use of prison labour helped the mine keep production costs low, such that Mitsui was able to sell the coal cheaper than anyone else on the Asian market.31

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figures 3-8: Details from the 8 m long picture scroll of prison labour Shūjin rōdō emaki (囚人労働絵巻), produced between 1881 and 1889 by an unknown prisoner in Sorachi prison. © Courtesy of the National Museum of Japanese History.

The scroll is remarkable as it highlights how the modern Japanese railway depends on coal extracted by prisoners from Horonai coal mines. The depictions include details of an accident: a fire with many casualties among the prisoners.

Although the Ainu did not work alongside the convicts, they often cooperated with new settlers, who were frequently in need of Ainu assistance and expertise.32 This was still the case in October 1886, when a group of 170 men from Kagoshima arrived in Kushiro to work as prison guards for the third central prison, which had opened on 15 November 1885 in the village of Shibecha. In a focus group interview, one of the prison guards, Maruta Toshio, described his first encounter with the Ainu who were sent to assist him and other guards:

[W]e got eight Ainu as errand boys to help us. The hair of these Ainu was so thick that it was impossible to tell whether they had eyes, and they wore a short garment reaching down to their navel that is hard to describe. I wondered whether these were local people (dojin) or Ainu. I thought we would be afraid of the Ainu, but the Ainu saw us and were frightened. One of the errand boys dropped a teacup. It was a situation in which we feared each other and were surprised by each other. When we later asked [the vice-warden and a head guard] why the Ainu were frightened upon seeing us, they answered that our Kagoshima customs were surprising, being dressed in short garments made of dappled cotton fabric which did not cover our ankles.33

This excerpt from Maruta’s account shows how little details could lead to serious cultural shock between the Ainu of Hokkaidō and the Japanese immigrants from Kyūshū. It is important to note that the shock was caused not so much by biological difference as by differences in the design and length of their clothes. Maruta even wondered whether the errand boys were Ainu or local settlers. This suggests that in this context, “race” or “racial” difference was perceived more through geographical and cultural difference, than through biological traits.

From 1886 onwards, prison labour in Hokkaidō drove coal and sulphur mining, as well as road construction. This trend corresponded with the general push to intensify the colonization process in Hokkaidō, particularly as the Meiji government suspected the three-ken government of inefficiency. Itō Hirobumi therefore sent Kaneko Kentarō – a government official who had studied law at Harvard University – to Hokkaidō to inspect the region and draft a plan for further development. Like Itō’s letter, Kaneko’s report discusses the role of prison labour in development. He pressed for immediate road construction and suggested using prisoners for the work over common labourers:

If common labourers are hired for these extremely arduous tasks and are unable to bear the workload, we will be in a situation where wages will rise to a very high level. For this reason, prisoners from the prefectures of Sapporo and Nemuro should be relocated and deployed here. These are rough hoodlums by nature, and if they are unable to bear the work and are broken by it, then the situation is different than that of common labourers, who leave behind wives and children, and whose remains must be interred in the ground. And furthermore […] if they are unable to bear it and perish, then the reduction of these persons is, in light of today’s situation where reports are made on the extreme difficulty of funding prisons, to be considered an unavoidable strategy. […] Therefore, I ask that such convicts be gathered and put to these arduous tasks that common labourers cannot bear.34

In this passage, Kaneko drew an almost inhuman picture of prisoners. Alluding to the casualties from such hard labour, he suggested that the social costs of a dead convict are far less compared to the social costs of a dead common labourer. Indeed, he (wrongly) assumed that deceased convicts have no family members. Moreover, he suggested that they did not need a proper funeral. Thus, by denying the prisoners’ roles as husbands, sons, and fathers, and by denying them any right to a funeral, Kaneko denies their existence as social beings. Instead, he describes them as dispensable, subaltern people, who have no other role in history aside from having their labour exploited for development policies drafted by a dominant ruling class.

However, from the late 1880s onwards, the Home Office was clearly interested in reforming Japanese prisons, so as to accommodate Westerners as well. Ogawa Shigejirō, an academic advisor for prison affairs to the Home Office who had a personal interest in German penology, and who founded a professional journal on police prisons in 1889, compiled a new set of national prison rules that same year.35 At the same time, the media increasingly reported on the prisoners’ difficult working conditions and prison escapes. Especially during the 1890s, the Hokkaidō Mainichi Shinbun featured stories of escape attempts almost daily. These stories, in turn, fuelled the fear of prisoners among the local population to such an extent that there were hunts for prison escapees. One other concern was the establishment of entertainment houses near the prisons. In Shibecha, for instance, the influx of single men working as guards in Kushiro prisons led to a number of taverns and bath houses opening in the area. Because these places were also associated with prostitution, local residents reportedly began worrying about moral decay.36 Eventually, in 1894, prisoners’ outdoor labour came to an end.

Tako labour and Korean labour

Convict labour was eventually replaced with other forms of indentured labour, fed by agents who recruited unemployed and homeless people in big cities like Tokyo and Osaka. The agents promised good work on construction sites and introduced unemployed people to brokers, who gave them cash in advance for food and alcohol. Eventually, the workers became contracted to repay the money they had received up front, at which point, they were sent to Hokkaidō to work in the mines or on construction sites. These workers were commonly referred to as tako (octopus). They were typically accommodated in camps called “tako camp” (takobeya), which forced the workers to remain on the camp’s premises. There was also a hierarchy among takobeya workers: a foreman (bōgashira) was the highest rank, and men in this position supervised other workers and enforced discipline. Kobayashi Takiji described this atmosphere in his 1929 novel The Crab Cannery Ship:

When workers on the mainland grew “arrogant” and could no longer be forced to overwork, and when markets reached an impasse and refused to expand any further, then capitalists stretched out their claws, “To Hokkaido, to Karafuto!” There they could mistreat people to their hearts content, ride them brutally as they did in their colonies of Korea and Taiwan. The capitalists understood that there would be no one to complain.37

Kobayashi thus drew a direct link between the labour exploitation in Hokkaidō and Karafuto (Sakhalin), and that in other colonies of the Japanese Empire.

From 1890 onwards, tako workers built the roads to the coal mines in Muroran and Yūbari. Tako workers were also sent to work in these coal mines under extremely dangerous conditions. In spite of increasing mechanization, gas explosions killed and injured many miners. In the Yūbari mine alone, a gas explosion in 1908 killed 90 men. In April 1912, another explosion killed 269 and in December that same year, another 216 men were killed. Two years later, in 1914, over 400 people died after a gas line burst in Yūbari. Takolabour was abolished only after the end of the Pacific War. Kobayashi summarizes the tako workers’ miserable situation:

The name for workers in Hokkaido was “octopus.” In order to stay alive, an octopus will even devour its own limbs. It was just like that! Here a primitive exploitation could be practiced against anyone, without any scruples. It yielded loads of profit. What’s more such doings were cleverly identified with “developing the national wealth,” and deftly rationalized away. It was very shrewdly done. Workers were starved and beaten to death for the sake of “the nation.”38

To be sure, the development of Hokkaidō’s coal mining industry was essential to the development of Japan as a capitalist nation. Throughout the First World War, Hokkaidō coal became more important than ever, and the mines demanded ever increasing numbers of workers. Accordingly, the number of women working underground rose. By 1916, 2382 women worked as coal miners in Hokkaidō. It seemed that children were also working in the mining industry: Kobayashi, for instance, describes them pushing loaded mine cars from one station to the next. Yet, because there were still too few Japanese labourers, in 1916, the Hokutan company hired thirty-three Korean labourers for the Yūbari mine. By 1917, there were already 192 Koreans working in the mine, and by 1918, that number had grown to 447 workers.39 Ten years later, in 1928, there were 6,416 Koreans in Hokkaidō, with half of them working in coal mines.40 The wages and working conditions for these Korean labourers were usually even worse than those for the Japanese miners. Korean miners were frequently forced into the most difficult and dangerous jobs as underground workers and were therefore much more vulnerable to injuries and fatal accidents. Kobayashi described the unequal power relations and the racism at the worksites: “Everyone envied the prisoners who worked in a nearby jail. Koreans were treated most cruelly of all, not only by the bosses and overseers but by their fellow Japanese laborers.”41

Figure 9: Korean forced labourers in Hokkaidō, © The Hankyoreh.

This passage highlights differences between three different groups of subaltern workers: the prisoners, the tako workers, and the Korean labourers. It is significant that at the time of writing his novel, in 1929, Kobayashi saw the prisoners’ working conditions as better than those of the other workers. His perception reflects how the 1894 abolishment of outdoor prison labour led to the view of improved working conditions in the prisons, such that they inspired envy among Japanese tako labourers and Korean workers who filled the convicts’ places in the mining industry and road constructions. Moreover, the racism of Japanese miners toward Korean miners highlights the absence of unity between different groups of subaltern people. Even so, Korean labourers did not simply accept their exploitation passively. For example, on 24 March 1918, a group of 82 Korean workers arrived in Yūbari from Busan. Upon their arrival, they complained to the broker that the conditions in Yūbari were different from the working conditions promised to them in Korea. According to a local newspaper, some of the workers felt that their lives were in danger and fled to a local police station. However, neither the local representative (daihyō), nor the interpreter, nor the broker himself were able to calm the Korean workers’ protest. The following day, on March 25th, the Korean workers expressed their anger through violent action. An eyewitness recalled that an alarm bell was ringing, and that someone was shouting that the Korean workers were rioting. Apparently, some Korean workers had wrapped their right hands with tenugui (a piece of thin cotton) and broken the police station window.42 In 1919, miners formed a union in Yūbari, and in 1920, the first Korean labour organization in Japan was established as a section of the Yūbari Federation of the National Union of Miners. Nevertheless, the use of Korean forced labour continued into wartime, when an estimated 145,000 Korean workers and 16,000 Chinese workers were brought to Hokkaidō to work in coal mines and on construction sites.43

Concluding remarks

This article has argued that different forms of forced labour crucially supported the colonization of Hokkaidō – and thus, the building of the Japanese empire – both before and during the Meiji period. Different forms of forced labour included the indigenous Ainu population, convicts in ninsoku yoseba and the three central prisons, indentured tako workers, as well as labourers recruited from the colonies. I suggest that there is an interesting parallel between these peoples who were forced to work for the Tokugawa and Meiji colonization of Ezo/Hokkaidō: they were all subaltern, i.e. politically marginalized, and even perceived as “dispensable.” A closer look at the various subaltern people forced to work for the colonization of Ezo/Hokkaidō highlights how the intersection of social categories, such as ethnicity, age, gender, and political-economic status shaped the form of labour exploitation: racism against the Ainu and Korean labourers both before and after the Meiji Restoration involved an ethnic dimension to their subaltern experience, and highlights the existence of unequal power relations even among the subaltern. The convicts in Hokkaidō’s central prisons were there largely because of their political activism against the Meiji government. After the abolishment of outdoor prison labour in 1894, however, the situation in prisons seems to have improved to such an extent that in 1929, Kobayashi wrote that prisoners’ working conditions were the point of envy among Japanese tako labourers and Korean workers. In terms of generational power relations, I mentioned that children were recruited for the basho seido in the mid-19th Century and worked alongside adults in Hokkaidō’s coal mining industry in the early 20th Century. Concerning gendered forms of labour, my article drew attention to the sex work of Ainu concubines, to female inmates in ninsoku yoseba, the sex industry around prisons, and the exploitation of women in the coal mines of Hokkaidō. Compared to the exploitation of men’s work, however, records of children and women’s experiences are even more difficult to find: “If, in the contest of colonial production, the subaltern has no history and cannot speak, the subaltern as female [and the subaltern as child, PJ] is even more deeply in shadow.”44

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Pia M Jolliffe is a Fellow at Blackfriars Hall, University of Oxford, where she teaches early modern and modern Japanese history. Her most recent book publication is a monograph entitled Prisons and Forced Labour Japan. The Colonization of Hokkaido, 1881-1994 (Routledge, 2019). [email protected]

Sources

Blaxell, Vivian. “Designs of Power: The ‘Japanization’ of Urban and Rural Space in Colonial Hokkaidō.” The Asia-Pacific Journal 9, no. 35/2 (2009).

Botsman, Daniel. Punishment and Power in the Making of Modern Japan. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Bowen, Roger W. Rebellion and Democracy in Meiji Japan. A Study of Commoners in the Popular Rights Movement. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 1980.

Enomoto Morie. Hokkaidō no rekishi. Sapporo: Hokkaido shinbunsha, 1999.

Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. London: The Eclectic Book Company, 1999.

Hirano Katsuya. “Settler Colonialism in the making of Japan’s Hokkaido.” In The Routledge Handbook of the History of Settler Colonialism, edited by Edward Cavanagh and Lorenzo Veracini, 268-277, London: Routledge, 2017.

Howell, David L. Geographies of Identity in Nineteenth-Century Japan. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2005.

Hudson, Mark J. “Ainu and Hunter-Gatherer Studies.” In Beyond Ainu Studies. Changing Academic and Public Perspectives, edited by Mark James Hudson, ann-elise lewallen and Mark K. Watson, 117-135. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2014.

Irish, Ann B. Hokkaido. A History of Ethnic Transition and Development of Japan’s Northern Island. Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland, 2009.

Jolliffe, Pia. Prisons and Forced Labour in Japan. The Colonization of Hokkaido, 1881-1894. London: Routledge, 2019.

Kayano Shigeru. Our Land Was the Forest. An Ainu Memoir. Boulder, San Francisco and Oxford: Westview Press, 1996.

Ketelaar, James Edward. “Hokkaidō Buddhism and the Early Meiji State.” In New Directions in the Study of Meiji Japan, edited by Helen Hardarce H. and Adam L. Kern, 531-548 .Leiden: Brill, 1997.

Kobayashi Takiji. “The Crab Cannery Ship.” In The Crab Cannery Ship and Other Novels of Struggle, 19-96, Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2013.

Koike Yoshitaka. Kusaritsuka: Jiyūminken to shūjin rōdō no kiroku. Tokyo: Gendaishi shuppankai, 1981.

Kuwabata Masato. Kindai Hokkaidōshi kenkyū josetsu. Sapporo: Hokkaidō daigaku tosho kankōkai, 1982.

Maruta Yoshio. “Kushiro shūjikan wo shinobu zadankai.” In Hokkaidō shūjikan ronkō edited by Takashio Hiroshi and Nakayama Kōshō, 339-367, Tokyo: Kōbundō, 1997.

Miyamoto Takashi. “Convict Labor and Its Commemoration: the Mitsui Miike Coal Mine Experience,” The Asia-Pacific Journal. Japan Focus 15, no. 1/3 (2017).

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. “Long Journey Home: A Moment of Japan-Korea Remembrance and Reconciliation,” The Asia-Pacific Journal. Japan Focus 13, no. 2, 35 (2015).

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. “Northern Lights: The Making and Unmaking of Karafuto Identity,” The Journal of Asian Studies 60, no.3 (2001): 645-671.

Oda Hiroshi. “Unearthing the history of minshū in Hokkaido. The case study of the Okhotsk People’s History Workshop.” In Local History and War Memories in Hokkaido, edited by Philip Seaton, 129-145, London: Routledge, 2016.

Siddle, Richard. Race, Resistance and the Ainu of Japan. London and New York: Routledge, 1996.

Shigmatsu Kazuyoshi. Nihon gokuseishi no kenkyū. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2005.

Shigematsu Kazuyoshi. Hokkaidō gyōkei shi. Tokyo: Zufu shuppan, 1970.

Solís, Jesús. “From “Convict” to “Victim”: Commemorating Laborers on Hokkaido’s Central Road,” The Asia-Pacific Journal. Japan Focus 17, no. 6/1 (2019).

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Tabata Etsuko (1982) “Yūbari to chōsen jin” In Waga Yūbari, Shirarezaru yama no rekishi edited by Yūbari hataraku mono no rekishi wo kiroko suru kai, 245-251, Sapporo: Kikanshi insatsu shuppan kikaku-shitsu, 1982.

Takahashi Tomio. “Ezo.”, Encyclopedia Nipponica. Japan Knowledge, accessed 15 January 2020.

Tipton, Elise K. Modern Japan. A social and political history. London and New York: Routledge, 2008.

Walker, Brett. The Conquest of Ainu Lands Ecology and Culture in Japanese Expansion, 1590-1800. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Weiner, Michael. Race and Migration in Imperial Japan. London and New York: Routledge, 1994.

Yohei Achira. “Unearthing takobeya labour in Hokkaido.” In Local History and War Memories in Hokkaido, edited by Philip Seaton, 146-158, London: Routledge, 2016.

Komori Yōichi. “Introduction.” In The Crab Cannery Ship and Other Novels of Struggle. Transl. by Željko Cipriš, 1-17, Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2013.

Yūbari hataraku mono no rekishi wo kiroko suru kai ed. Waga Yūbari, Shirarezaru yama no rekishi. Sapporo: Kikanshi insatsu shuppan kikaku-shitsu, 1982.

Notes

1 I thank Ayelet Zohar, Mark Selden and Joelle Tapas for their comments on earlier versions of this article.

2 Miyamoto Takashi, “Convict Labor and Its Commemoration: the Mitsui Miike Coal Mine Experience,” The Asia-Pacific Journal. Japan Focus 15, no. 1/3 (2017).

3 Jesús Solís, “From “Convict” to “Victim”: Commemorating Laborers on Hokkaido’s Central Road,” The Asia-Pacific Journal. Japan Focus 17, no. 6/1 (2019).

4Komori Yōichi, introduction to The Crab Cannery Ship and Other Novels of Struggle. Transl. by Željko Cipriš (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2013), 1.

5 Michele Mason, Dominant Narratives of Colonial Hokkaido and Imperial Japan. (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012); Philip Seaton, “Japanese Empire in Hokkaido,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History, accessed 20 July 2020.

6 Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “Creating the Frontier: Border, Identity and History in Japan’s Far North,” East Asian History 7, 1-24.

7 Philip Seaton, “Grand Narratives of Empire and Development”, In Local History and War Memories in Hokkaido, ed. Philip Seaton (London: Routledge, 2016), 52.

8 Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks (London: The Eclectic Book Company, 1999), 202.

9 Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 199), 273.

10 Shigematsu Kazuyoshi, Nihon gokuseishi no kenkyū (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2005), 169; Pia Jolliffe, Prisons and Forced Labour in Japan. The Colonization of Hokkaido, 1881-1894 (London and New York: Routledge, 2019); Yūbari hataraku mono no rekishi wo kiroko suru kai ed, Waga Yūbari, Shirarezaru yama no rekishi (Sapporo: Kikanshi insatsu shuppan kikaku-shitsu, 1982), 3.

11 Oda Hiroshi, “Unearthing the history of minshū in Hokkaido. The case study of the Okhotsk People’s History Workshop,” In Local History and War Memories in Hokkaido, ed. Philip Seaton (London: Routledge, 2016), 139.

12 Takahashi Tomio, “Ezo,” Encyclopedia Nipponica, Japan Knowledge, accessed 15 January 2020.

13 Mark J. Hudson, “Ainu and Hunter-Gatherer Studies,” In Beyond Ainu Studies. Changing Academic and Public Perspectives, ed. by Mark James Hudson, ann-elise lewallen and Mark K. Watson (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2014), 131.

14 Brett Walker, The Conquest of Ainu Lands Ecology and Culture in Japanese Expansion, 1590-1800 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 21-26.

15 Kayano Shigeru, Our Land Was the Forest. An Ainu Memoir (Boulder, San Francisco and Oxford: Westview Press, 1996), 27-28.

16 Walker, 2001, The Conquest of Ainu lands, 188-190.

17 Richard Siddle, Race, Resistance and the Ainu of Japan (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), 36-37.

18 David L. Howell, Geographies of Identity in Nineteenth-Century Japan (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2005), 144-145.

19 James Edward Ketelaar, “Hokkaidō Buddhism and the Early Meiji State,” In New Directions in the Study of Meiji Japan, ed. by Helen Hardarce H. and Adam L. Kern (Leiden: Brill, 1997), 536-540.

20 Shigematsu Kazuyoshi, Hokkaidō gyōkei shi (Tokyo: Zufu shuppan, 1970), 151-152.

21 Hirano Katsuya, “Settler Colonialism in the making of Japan’s Hokkaido,” In The Routledge Handbook of the History of Settler Colonialism, ed. by Edward Cavanagh and Lorenzp Veracini (London: Routledge, 2017), 268-277.

22 Tessa Morris-Suzuki,“Northern Lights: The Making and Unmaking of Karafuto Identity,” The Journal of Asian Studies 60, no. 3 (2001): 648.

23 Shigematsu, 2005, Nihon gokuseishi, 174.

24 Shigematsu, 2005, Nihon gokuseishi, 176-177.

25 Elise K. Tipton, Modern Japan. A social and political history (London and New York: Routledge, 2008), 46.

26 Jolliffe, 2019, Prisons and Forced Labour in Japan, 31-32.

27 Roger W. Bowen, Rebellion and Democracy in Meiji Japan. A Study of Commoners in the Popular Rights Movement (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press,1980), 107-109.

28 Jolliffe, 2019, Prisons and Forced Labour, 34.

29 Vivian Blaxell, “Designs of Power: The ‘Japanization’ of Urban and Rural Space in Colonial Hokkaidō,” The Asia-Pacific Journal 9, no. 35/2 (2009).

30 Koike Yoshitaka, Kusaritsuka: Jiyūminken to shūjin rōdō no kiroku (Tokyo: Gendaishi shuppankai, 1981), 100

31 Enomoto Morie (1999) Hokkaidō no rekishi (Sapporo: Hokkaido shinbunsha, 1999), 260; Daniel Botsman, Daniel, Punishment and Power in the Making of Modern Japan (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2005), 185.

32 Ann B. Irish, Hokkaido. A History of Ethnic Transition and Development of Japan’s Northern Island. (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland, 2009), 194.

33 Maruta Yoshio, “Kushiro shūjikan wo shinobu zadankai,” In Hokkaidō shūjikan ronkō, ed. by Takashio Hiroshi and Nakayama Kōshō (Tokyo: Kōbundō, 1997), 344.

34 Kaneko, cited in Shigematsu Kazuyoshi. Hokkaidō no gyōkei shi (Tokyo: Zufu shuppan, 1970), 174.

35 Botsman, Prison and Punishment, 194-196.

36 Kuwabata Masato, Kindai Hokkaidōshi kenkyū josetsu (Sapporo: Hokkaidō daigaku tosho kankōkai, 1982), 178.

37 Kobayashi Takiji, The Crab Cannery Ship and Other Novels of Struggle (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2013), 53.

38 Kobayashi, 2013, The Crab Cannery Ship, 54-55.

39 Irish, 2009, Hokkaido, 218, Kobayashi, 2013, The Crab Cannery Ship, 55.

40 Michael Weiner, Race and Migration in Imperial Japan (London and New York: Routledge, 1994), 135.

41 Kobayashi, 2013, The Crab Cannery Ship, 54.

42 Tabata Etsuko, “Yūbari to chōsen jin” In Waga Yūbari, Shirarezaru yama no rekishi, ed. by Yūbari hataraku mono no rekishi wo kiroko suru kai (Sapporo: Kikanshi insatsu shuppan kikaku-shitsu, 1982), 246-248.

43 Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “Long Journey Home: A Moment of Japan-Korea Remembrance and Reconciliation,” The Asia-Pacific Journal. Japan Focus 13, no. 2/35 (2015).

44 Spivak, 1999, A Critique of Postcolonial Reason, 274.