This article assesses relations between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, or Burma, in light of the military coup d’état which took place on February 1, 2020. This event caused an unexpected crisis in ties between the two neighboring countries, which the Burmese have traditionally described as pauk paw relations, those between “distant cousins.

The well-known proverb, “sleeping in the same bed, dreaming different dreams,” aptly describes this relationship, especially since 1988. In that year, the isolationist, socialist regime of General Ne Win collapsed and was violently replaced by a younger generation of generals, initially loyal to Ne Win, who formed a junta known as the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC, after 1997 known as the State Peace and Development Council). Both before and after this power seizure, the Burmese military killed thousands of demonstrators nationwide.

Consciously, the generals sought to mimic China’s economic success by fostering economic liberalization while retaining a tight grip on political power, a strategy that was also being followed by communist Vietnam since the opening of its 1986 Doi Moi reforms. They had considerable sympathy for Deng Xiaoping when he ordered the suppression of political dissidents, resulting in the Tiananmen massacre in Beijing on June 4, 1989. Deng’s determination to aggressively protect the supremacy of the Chinese Communist Party and prevent any alternative, more democratic political evolution found resonance in the leadership of the Tatmadaw, Burma’s armed forces, and some observers suggest that Deng’s use of violent force had been inspired by the Tatmadaw’s suppression of protesters the year before (Seekins, 1997: 532).

A series of foreign investment laws were decreed by the junta following the establishment of the SLORC on September 18, 1988, but the generals’ dreams of Burma becoming the next “tiger” economy in Southeast Asia were thwarted not only by their own inept and corrupt management, but also by sanctions imposed by western countries, especially the United States and the European Union. Even Japan, Burma’s largest donor of official development aid (ODA) at the time, exercised self-restraint in extending new loans and grants during the SLORC/SPDC years (Seekins, 2007: 115-148). China and members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (especially Thailand, Singapore and Malaysia) ignored the call for sanctions by the West and endeavoured to enrich themselves through “constructive engagement” with Burma’s junta. One of the first steps in the development of a flourishing Sino-Burmese economic relationship was the normalization of legal trade along the 2,227 kilometre-long border between Burma and China in 1989 and the sale of weapons by Beijing to Rangoon the following year, which totalled the equivalent of some US$1.0-US$1.4 billion (Lintner, 1999: 387-389, 470).

There were some rough spots in Sino-Burmese relations after 1988, including in 2009 when fighting broke out between the Tatmadaw and insurgents belonging to the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MDNAA, also known as the Kokang Group) in the Kokang region of northeast Shan State, which caused 37,000 largely Han Chinese Kokang people to flee to Chinese soil (Seekins, 2017: 306). In March 2015, bombs were mistakenly dropped by the Burmese air force across the border in Yunnan Province, killing five Chinese nationals; Beijing responded saying it would take stern action if such an incident happened again. Analyst Sun Yun wrote that this was “the worst day in Sino-Myanmar relations since 1967,” when the Chinese embassy was attacked and many Chinese nationals killed (“Selling the Silk Road Spirit,” 2019).

In 2011, the SPDC junta was replaced by a hybrid civilian-military government under the 2008 Constitution and it seemed that President (and retired General) Thein Sein was departing from the Chinese model by promoting political as well as economic liberalization. A highly sensitive issue in bilateral ties was his decision to suspend construction of the giant Myitsone Dam in northernmost Kachin State, which was to generate electricity primarily for China’s Yunnan Province rather than Burma (Seekins, 2017: 372, 373). In some ways a bolder democratic reformer than Aung San Suu Kyi herself after she gained power in 2015, Thein Sein said the completion of the dam required the complete understanding of Burma’s people (Thant Myint-U, 2020, 145-147; Sun Yun, 2012: 58, 59).

The priorities of Burma’s ruling generals were to pursue economic development utilizing China’s aid and investment. Moreover, the Tatmadaw came to depend on imports of made-in-China arms after 1989, although it also acquired weapons and militarily-applicable technology from Russia, Israel, Singapore, and, reportedly, North Korea. Various border groups, including the United Wa State Army, the Kachin Independence Army and the MDNAA, relied on China’s financial or other support to keep their movements viable while “crony capitalists” close to the ruling generals benefited from China’s growing economic presence after 1989, especially in Upper or central Burma and the country’s second largest city, Mandalay.

Founding of the China-Burma Friendship Association in 1952 (Public Domain)

The chief interest of China’s central government in Beijing has been to promote political stability inside Burma not only to profit from its internal markets and exploit its abundant natural resources (especially energy resources), but also to further an emerging geopolitical vision of the country serving as a means of “connectivity” between China and the Indian Ocean and beyond. In 2013, President Xi Jinping announced his ambitious One Belt, One Road Initiative, in which Burma became a key piece in Beijing’s geopolitical jigsaw puzzle, extending its influence into areas that previously had not historically been subject to the expansion of Chinese military, political or cultural power: South Asia (with the exception of an increasingly antagonistic India), West Asia, East and Central Europe and Africa, where China has a large and growing economic presence.1

Chinese fears that after Daw Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy, won a landslide victory in the General Election of November 2015 she would promote closer relations with the West at China’s expense proved unfounded. As western countries grew increasingly critical of her after she expressed indifference to the Tatmadaw’s persecution of Muslim Rohingyas in Rakhine (Arakan) State in 2017, it became clear that Beijing provided for her, as well as for the generals with whom she uneasily co-existed, an indispensable alternative in order to evade a possible new rollout of western sanctions. Her visit to the International Court of Justice in The Hague in 2019 to deny that the Tatmadaw had been involved in genocide of Rohingyas only reaffirmed this pivot away from her former western supporters toward China and other Asian countries.

The coup d’état of February 1, 2021, however, upset the expectations of both Daw Suu Kyi and the Chinese. There is evidence to suggest that Beijing had very mixed feelings about the establishment of a new martial law regime, the State Administration Council (SAC), headed by commander-in-chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. These reservations seemed to increase after the SAC began escalating deadly violence against civilian protesters, most of them unarmed, leading to more than 740 deaths of ordinary citizens, including children, by late April. With long-term instability and even civil war inside Burma almost a certainty, the coup threatens not only specific Chinese economic interests but their ambitious vision of the One Belt/One Road, still promoted as a centrepiece of Xi Jinping’s diplomacy in 2021.

Sino-Burmese Relations before 1962

The histories of Burma and Vietnam, both located on the Indochina Peninsula, reveal a striking contrast: while (northern) Vietnam became a Chinese colony during the Han Dynasty and gained its independence only in 939 CE, resisting numerous invasions by China in the centuries following, Burma was largely shielded from projections of Chinese power by the existence of non-Chinese states in what is now Yunnan Province, which forms Burma’s entire land border with China. The state of Nan Zhao was not only a formidable opponent of the Tang Dynasty, but also extended its power into the central valley of the Irrawaddy River in Burma before entering into decline, to be succeeded by the state of Dali. Only in the thirteenth century, after Kublai Khan’s Mongol forces subjugated Dali and occupied Yunnan, did they enter territory controlled by unified Burma’s first royal house, the Pagan Dynasty (1044-ca. 1300), and contributed to its collapse early in the fourteenth century. The last major king of that dynasty, Narathihapate (r. 1254-1287), earned the inglorious title “the king who fled from the Chinese” (Seekins, 2017: 378, 379).2

Although a majority of Burma’s different ethnic groups speak languages related in some degree to Chinese, the evolution of Burma’s state, society and culture was deeply influenced by India rather than China, as reflected in its political and social thought, art, literature, customs and – above all – religion. Ninety percent of Burma’s population are adherents to Theravada Buddhism, which has been influenced profoundly by religious exchanges with Buddhist kingdoms in Sri Lanka.

Although a Manchu army invaded central Burma in the mid-17th century in search of one of the last princes of the Ming imperial house, it was only in the mid-eighteenth century that the Qing Dynasty posed a serious threat to Burma, now ruled by kings of the Konbaung Dynasty (1752-1885). During the 1760s, the Manchus launched several unsuccessful campaigns motivated by a dispute between the Burmese and Qing over control of the Shan (Tai) princedoms in what are now Yunnan and eastern Burma. Finally, a major invasion led by Ming Rui, a son-in-law of the Qian Long Emperor, and including elite Manchu and Mongol troops was initiated, but it too was defeated by Burmese armies led by the intrepid general Maha Thiha Thiru in 1769. The reigning king at that time, Hsinbyushin (1763-1776), earned the title “the king who fought the Chinese.” His military reputation was enhanced by the fact that while the Sino-Burmese War was taking place, his armies had also invaded Siam and captured the Thai capital of Ayuthia in 1767.3 The Sino-Burmese Treaty of Kaungton included, as a face-saving measure, the promise of the Burmese to send a tribute mission to Beijing every ten years to pay homage to the Qing Emperor; but a major result of the war was the establishment of a rough boundary between Shan States ruled by China and those ruled by Burma which was recognized up to the end of the British colonial period and formed the basis for the contemporary boundary agreement between Burma and China in 1961 (Seekins, 2017: 147, 148, 250).

The Chinese presence in Burma was stabilized during the period of British colonial rule. Having annexed Lower Burma in wars occurring in 1824-1826 and 1852, the British occupied Upper Burma and its royal capital of Mandalay in 1885, sending King Thibaw into exile in India and bringing an end to the Konbaung Dynasty. The British-enforced colonial economy carried out limited direct trade with China, which was then in a state of considerable instability, save for commerce initiated by so-called “mountain Chinese,” also known as Panthays, a Muslim minority located in Yunnan whose pack trains wound their way south as far as Rangoon. They had carried out a revolt against the Qing authorities in Yunnan between 1856 and 1873 but found safety under the umbrella of British rule.

Kokang, a small state located in the eastern Shan States, was established by Chinese supporters of the Ming Dynasty fleeing the Manchus in the seventeenth century. Its hereditary ruler or heng, a member of the Yang family, controlled a small population of Han Chinese and indigenous ethnic groups. In the early twentieth century, Kokang became a centre for the notorious cultivation and trade in opium which served a huge market in China (Seekins, 2017: 305, 306).

Large cities such as Rangoon (Yangon), Moulmein (Mawlamyine) and Mandalay had overseas Chinese communities, mostly people from Guangdong and Fujian Provinces similar to those residing in Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore. Ties between Overseas Chinese in Lower (southern) Burma and those living in the British-ruled Straits Settlements, especially Penang, were strong (Thaw Kaung, 2004). Rangoon’s “Chinatown” (B. Tayoketan) is still located in the western part of the city’s central business district (Latha and Lanmadaw Townships), a distinct area the streets of which are lined with Chinese temples, restaurants and shops, of which gold shops are particularly prominent.

In 1931, the colonial capital of Rangoon had a population of only around 7.6 percent (Overseas) Chinese, mostly located in Tayoketan, while residents of South Asian origin comprised the majority, or 53.2 percent. Indigenous Burmese comprised only 35 percent (Seekins, 2011: 39). These demographics show that the economic focus of Rangoon and Lower Burma was on British India (present-day India, Pakistan and Bangladesh) rather than on China. In fact, until 1937, Burma was a province of British India. Between South Asians, mostly Hindus and Muslims, and Buddhist Burmese there was considerable racial friction and even violence during the colonial era; but relations between the indigenous people and Chinese residents tended to be more amicable, due in large measure to the fact that as in Thailand, the Chinese often assimilated into Burmese society and even adopted the Theravada Buddhist religion (Ibid., 39-41; Lintner, 1999: 67).

The famous “Burma Road” linking the port of Rangoon with the Yunnan capital of Kunming and Jiang Jieshi’s wartime capital of Chongqing was constructed in the late 1930s by the Allies to provide Jiang’s government with vital wartime supplies.4 However, it was cut off by Japanese forces in 1942. In the unsuccessful attempt to defend Burma from Japanese occupation, British forces fought alongside the Kuomintang army in northern Burma. Although the Japanese did not extend their control into Yunnan, which was ruled by a local warlord, Long Yun, the Burma-China border became a vital front in the War. A remote area that had been previously the neglected “backyard” of both China and Burma began to be part of a huge “geography lesson” learned by wartime newspaper readers in New York, London, New Delhi and Tokyo. In 1944, “Merrill’s Marauders,” an American military unit, entered northern Burma from India and captured the airstrip at Myitkyina in what is now Kachin State, lost it to a Japanese counter-offensive and then recaptured it in August. From Myitkyina, Allied aircraft could fly more easily to bring supplies to Jiang’s wartime capital. The Allies also built the 1,726 kilometre-long Ledo Road, which connected India and China by land via northern Burma (Seekins, 2017: 125, 320, 347, 575-577). Because of the War, the hitherto remote Burma-China border area was opened up, temporarily, to the outside world and Myitkyina’s airport became one of the busiest in the world.

Although British forces, composed largely of Indian soldiers, liberated (or re-occupied) the country in 1945, fighting bloody battles in Upper Burma, the British colonial period was almost at an end. Burma achieved independence on January 4, 1948, and nationalist leader U Nu became prime minister of the new Union of Burma.

Relations between the Union of Burma and the People’s Republic of China, officially proclaimed in October 1949, were cordial. Prime Minister U Nu, who would become a fervent proponent of the Non-Aligned Movement, was the first non-Soviet bloc leader to recognize the communist regime. Rangoon and Beijing found a common purpose when so-called Chinese Irregular Forces, loyal to the Nationalists or Kuomintang, sought to open a “second front” against the communists (the first being Taiwan) in the China-Burma border region. Although a joint military operation by China’s People’s Liberation Army and the Tatmadaw dealt a hard blow to these intruders in 1961, their remnants continued to play a major role in local unrest and the opium economy inside the infamous “Golden Triangle.” The appearance of the Chinese Irregular Forces in the Shan States also led to great tension between U Nu’s government and Washington, since the US Central Intelligence Agency underwrote the establishment of Kuomintang bases in this corner of Burma (Seekins, 2017: 309; Lintner, 1999: 111-120).

A major achievement of the government of U Nu was completion of a border agreement with China in January 1961, which resulted in the mutual exchange of small patches of territory (Seekins, 2017: 144, 145). But loss of territory in Kachin State to the Chinese alienated the local Kachins, and was a factor in their establishment of a major ethnic armed organization, the Kachin Independence Army, during the 1960s (Lintner, 1999: 486).

Sino-Burmese Relations during the Ne Win Period, 1962-1988

Prime Minister U Nu approved of a temporary “Caretaker Government” headed by Tatmadaw commander General Ne Win to deal with deep conflict among civilian politicians (it lasted from 28 October 1958 to April 1960), but Burma entered a long, dark valley of military rule, lasting for decades, following Ne Win’s coup d’état of March 2, 1962. He set up a Revolutionary Council (RC) composed of military officers who ran the country by decree and also established a “revolutionary party” known as the Burma Socialist Programme Party, or BSPP, with a parallel hierarchy which controlled state organs in a manner similar to the communist parties in China and the Soviet Union. The RC shut down most trade and other links with the outside world and pushed development of a self-sufficient socialist economy based on state ownership and management of major economic enterprises, which left the country suspended in a time warp of deepening poverty. The economy of the “Burmese Road to Socialism” was comprised of 23 state-owned corporations and a burgeoning black market that expanded to include a growing portion of the real as opposed to the official economy.

Chinese President Liu Shaoqi with Ne Win in 1966. (Public Domain)

Ne Win, whose original name was Shu Maung, was Sino-Burmese. However, he was careful to downplay his half-Chinese identity in order to solidify his image as a Burmese, or Burman, patriot.

Relations with Beijing continued to be cordial, including the provision of aid to Burma by the Chinese government; but as China fell into the throes of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in the mid-1960s, this changed abruptly. Schools had been nationalized and “Burmanized” under the Ne Win regime, but in Rangoon there were large numbers of restive ethnic Chinese students. When the Chinese embassy encouraged these students to support the Cultural Revolution by holding “struggle sessions” and wearing badges with Mao Zedong’s portrait on them, riots broke out in June 1967 between them and local Burmese, who were resentful over Chinese domination of the black market. In what were probably the worst riots since the colonial period, Burmese mobs killed local Chinese (the official number was 50, but the Chinese claimed there were several hundred victims) and burned their houses and shops. At the end of June, the mobs went on to attack the Chinese Embassy, and one of its officials was killed. The Chinese responded by withdrawing their ambassador, cutting off aid to Burma and using its media to condemn Ne Win as a “fascist” dictator. Many Overseas Chinese fled Burma. There was evidence that in order to find an outlet for popular economic frustrations under socialism, Ne Win secretly encouraged rioters to attack the Chinese (Mya Maung, 1992: 14, 15).

On January 1, 1968, Chinese-trained and equipped troops of the People’s Army (PA), the armed force of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB), stormed across the China-Burma border in northeast Shan State. They and subsequent reinforcements easily defeated local forces who were either independent or connected in some way to the Ne Win regime. The People’s Army soon became the strongest regional insurgency facing the Tatmadaw. It established bases, supported by China, in Kokang, the Wa districts and other parts of Shan State and regularly threw back Tatmadaw offensives sent against them by the central government. Although the aim of the new communist Northeast Command was the overthrow of Ne Win’s regime, it was never able to gain, or regain, military or political influence inside central Burma, where the majority Burmans lived and where the CPB had been previously active. Although the party’s leadership was Burman, by the 1980s most of the PA’s 15,000 soldiers were members of local ethnic minorities

Although many observers believe Chinese backing for the January 1968 establishment of communist bases in Shan State was meant to “punish” Ne Win for the anti-Chinese riots of the previous year, there is ample evidence to suggest that some form of Beijing-backed intervention had been planned and organised as far back as 1962, when Ne Win came to power.

China-Burma relations were normalized after the riots, and regular diplomatic ties restored, but the China-supported insurgency continued on the “two track” principle: that the Chinese state could have regular diplomatic ties with a foreign country like Burma, but the Chinese Communist Party would continue to pursue its own “fraternal relations” with the local communist party (Seekins, 1997: 528). During the 1950s and 1960s, about 140 members of the Communist Party of Burma sojourned in China, waiting for the opportunity to return home when the time was right for socialist revolution (Lintner, 1999: 170).

The Men who “Made Deals with the Chinese,” 1988-2011

If Narathihapate was the “king who fled from the Chinese” and Hsinbyushin was the “king who fought the Chinese,” the leaders of Burma’s second junta, the State Law and Order Restoration Council, were the men who “made deals with the Chinese.

In 1988, the greatest obstacle to deeper engagement between Rangoon and Beijing was the presence of the People’s Army in Shan State, though China’s support for this insurgency gradually declined over the years after it had entered Burma’s frontier region in 1968, causing it to increase opium sales in order to maintain its financial support (Seekins, 1997: 528). However, in March-April 1989 an event of immense importance took place: a mutiny of ethnic minority soldiers, mostly Wa, against the Burman leadership of the CPB, which led to the return of those leaders to exile in China and breakup of the People’s Army into four separate forces: the United Wa State Army (UWSA), the largest, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (or Kokang Group), the National Democratic Alliance Army, Eastern Shan State (NDAA-ESS) and the New Democratic Army (NDA) in Kachin State. These movements rejected revolutionary Marxism-Leninism, and devoted themselves to ethnic nationalism and continued participation in the highly lucrative drug trade (Lintner, 1999: 363, 364, 480).

Through the mediation of Lo Hsing-han, a Kokang Chinese who gained notoriety as the “king of the Golden Triangle” for his role in the drug trade, the SLORC was able to negotiate cease-fires with these four groups, which included not only a cessation of hostilities between the Tatmadaw and these reborn, post-communist forces but also recognition of their right to bear arms and control of the territories where they were based. On the SLORC’s side, General Khin Nyunt, the much-feared director of Burma’s Military Intelligence or secret police, played the key role in making these arrangements, which gave him considerable power and influence in the border areas until he was purged in October 2004. The cease-fires, which were expanded to include other ethnic armed organizations such as the Kachin Independence Army, the New Mon State Party, the Mong Tai Army (led by the second “king of the Golden Triangle,” Khun Sa, in central Shan State), and the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army – grew to a total of 18 armed groups by 1997 (Seekins, 2017: 136, 137).

The cease-fire system, through which Khin Nyunt assiduously built his power base, had profound consequences for Burma’s border areas, which previously had been largely beyond the Rangoon government’s control. Firstly, it allowed the junta to maintain a “divide and control” policy, preventing the ethnic forces from building a durable united front against the Burman-dominated military regime; and secondly, the period of relative peace in the border areas enabled China to cultivate a major economic presence not only in Shan State and other minority areas, but in Upper Burma as a whole, including the city of Mandalay.

The United Wa State Army commanded by Bao Youxiang prospered because of its major share of the production and export of narcotics by way of Yunnan and northern Thailand. It had, and still has, a well-equipped fighting force of 20,000 to 25,000 men and the infrastructure in and around its “capital” of Panghsang is superior to that of other parts of Burma. In order to expedite the drug trade, the UWSA in 1999 moved approximately 100,000 Wa villagers to the Thai-Burma border near the Thai border town of Tachilek. At that time, the UWSA was the one ethnic armed organisation that matched the Tatmadaw in firepower, a situation that remains true today. In effect, the Wa-dominated areas of Shan State and a patch of territory adjacent to Thailand constitute a nearly independent mini-state (Seekins, 2017: 558, 559).

Since 1989, Chinese involvement in the Burmese economy – and indirectly its society and politics – has involved diverse Chinese, Sino-Burmese and Burmese actors and relationships: the most visible was the support given by the Chinese state directly to the SLORC/SPDC, in the form of economic aid and weapons sales, as well as “moral” support, which was decisive in preventing the United Nations Security Council from taking any sort of concrete action against the junta’s numerous human rights abuses, including large-scale ethnic cleansing of people in minority areas like Shan and Karen States.5 Secondly, Chinese state-owned enterprises, such as Chinese army-owned Northern Industries Company, or NORINCO, formed ambitious joint ventures with companies owned by the Tatmadaw, especially two wholly-owned conglomerates, the Union of Myanmar Economic Corporation (UMEC) and the Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings (UMEH). The prevalence of state- or army-owned conglomerates in both countries made economic cooperation between them smoother than dealing with post-socialist Burma’s few private companies of any size. In addition, Chinese private enterprise, much of it based in Yunnan Province, entered Burma on its own and an unknown number of Chinese individuals left their homeland to sojourn inside Burma, much as their forebears had migrated to Lower Burma, Thailand, and the Malay Peninsula.6

Important players in this emerging economic system were the Chinese or Sino-Burmese leaders of ethnic armed organizations who controlled Burma’s flourishing drug economy. The most important figures were the Pheung, or Peng, brothers (Kokang Group), Lo Hsing-han (the first “king of the Golden Triangle”), Yang Molian (Kokang Group), and Khun Sa, also known as Chang Chi-fu (Mong Tai Army, the second “king of the Golden Triangle” after Lo was arrested). Bao Youxiang was an ethnic Wa, but like many of his fellow Was took a Chinese name. Both Lo and Khun Sa lived to enjoy comfortable retirements in Rangoon where they oversaw profitable companies, including Asia World, one of Burma’s largest, whose director was Lo’s son Steven Law (Seekins, 2017: 326).

During the SLORC/SPDC period, the cease-fires in Shan and Kachin States caused a rapid increase in the export of narcotics, including not only opiates but yaabaa (Thai, “crazy medicine”) or “speed” to markets around the world. Burma earned the dubious distinction, alternating with Afghanistan, of being the world’s largest exporter of drugs. The drug warlords acquired huge amounts of cash that needed to be laundered. To find a safe haven for this money, they invested in luxury hotels, housing developments and other projects in Mandalay and Rangoon, most of the purchasers being Chinese. Hlaing Thayar and Mingaladon Townships in Rangoon became the site for several of these developments, which look like upscale suburban housing in Southern California.7

Thant Myint-U quotes a Columbia University economist, Ronald Findlay, who said that “(t)he seed capital of the Burmese economy is heroin . . . if this is an exaggeration, it’s not a huge one” (Thant Myint-U, 2020: 50).

The Chinese presence was especially visible in booming border towns which grew up in the aftermath of the cease-fires. These include Panghsang (former “capital” of the CPB/PA, now controlled by the UWSA), Mong La (controlled by the National Democratic Alliance Army- Eastern Shan State), a vest pocket Sodom-and-Gomorrah popular with Chinese tourists in search of casinos, prostitutes, “ladyboys” and drugs), Muse (which is connected to China by two bridges, the older of which is called the “gun bridge” because shipments of arms from China were conveyed over it) and Ruili opposite Muse on the Chinese side of the border, which in recent years has also enjoyed explosive growth. Ruili and Wanding, another Chinese border town, gained special privileges through their Beijing-granted status as “special economic zones.”

Laiza, on the border with China in Kachin State, is considered the “capital” of the Kachin Independence Army but – perhaps because of the KIA’s largely Baptist leadership – possesses none of the Sodom-and-Gomorrah attractions of Muse or Mong La. In the border towns on the Burmese side, the atmosphere is quite un-Burmese, with Putonghua being spoken widely, Chinese restaurants lining the streets and renminbi being circulated instead of Burmese kyats. Casinos are located inside huge, gaudy hotels reminiscent of Macau or Las Vegas (Seekins, 2017: 316, 359, 364, 424).

Although Beijing stepped in early to develop trade links and provide the Tatmadaw with weapons, the largest quantities of foreign investment during the early SLORC years were provided by neighbouring Thailand and Singapore. China’s investments remained relatively modest until the first years of the 21stcentury, and by 2010-2011 China’s FDI (foreign direct investment) was the largest committed by any country, amounting to an estimated US$13.0 billion (Sun Yun, 2012: 63). Chinese official development assistance (ODA) was only around US$100 million in the mid-1990s, but grew to US$2.2 billion by 2012, making China Burma’s largest aid donor (Mizuno, 2016: 202-208). Chinese money was responsible for opening up the remotest parts of Burma’s frontier region to the outside world, including bridges over many rivers and reconstruction of the famous Ledo and Burma Roads.

In 2011, China became Burma’s largest single trade partner (Ibid., 199-202). Burma-China trade after 1988 began to resemble the “colonial” economies of Southeast Asia before World War II: the export of raw materials in exchange for consumer and manufactured goods. According to this writer:

In the 1993-94 period . . . China’s major exports to Burma were beverages, tobacco, textiles, garments, machinery, vehicles and transport equipment. The most important legal Burmese exports to China were food, wood, lumber, pearls and precious stones. Although Chinese machinery, vehicles and transport equipment can be utilized to upgrade Burma’s industry and infrastructure, most Chinese products, such as the large volume of beverage and tobacco imports, were directed toward “passive” consumer markets in a manner reminiscent of relations between a European metropole and an Asian colony during the early 20th century (Seekins, 1997: 529).

Mandalay, Burma’s second city, was transformed by the Chinese presence (see footnote 6, above). This city, comparable to Kyoto in Japan as a former royal capital and cultural centre, containing many Buddhist monasteries and sacred sites, became one big “Chinatown” as Chinese investors bought up property in its urban centre while local Burmese, unable to afford rising property prices, were forced to move to the city’s outskirts. During 1992-1993, as many as 50,000 Chinese settled in Mandalay, out of a total population of around 1.0 million (Seekins, 1997: 530). A common practice was for the sojourners to purchase the identity cards of deceased local people in northern Burma, whose deaths were not reported to the authorities. Possession of such cards enabled Chinese people to gain a Burmese passport with no questions asked (Lintner, 1993: 26).

Like Shan State and Mandalay, Kachin State felt the impact of the Chinese economic presence with not always beneficial consequences. This was especially true after the KIA signed a cease-fire in 1994. Although the truce marked the end of decades of bitter fighting, in subsequent years the SLORC/SPDC was able to take over many of Kachin State’s rich economic resources, including forests and the mines at Hpakant, which provided wealthy Chinese buyers in China and Southeast Asia with the world’s highest quality “imperial” jade. Many poor people from other parts of Burma worked at the mines under hellish conditions, including landslides that killed hundreds of them. Kachin State’s mountainsides were stripped of trees which were shipped off to China, causing severe environmental damage, and the miners at Hpakant provided Chinese markets with larger and larger quantities of jade, trade which amounted to billions of dollars. In northern Kachin State, the Hukawng Valley has deposits of gold and amber. But neither the KIA nor the local Kachins benefited. A disturbing sign of social decay was that as many as 80 percent of young Kachins were addicted to drugs. In 2011, there was renewed fighting between the Tatmadaw and the KIA, and tens of thousands of Kachins and other minorities were forced to flee their homes (Thant Myint-U, 2020: 169, 198, 199).

One of the more unusual aspects of the Burma-China relationship was “Buddhist diplomacy.” A Buddha tooth relic had been brought from India to China during the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE) and was enshrined at the imperial capital of Chang’an, but fell into obscurity until the early 20th century when it was discovered at a Buddhist monastery outside of Beijing. Although the People’s Republic of China is officially atheist, the Beijing government sent the tooth relic on “visits” to several neighbouring countries where local Buddhists could venerate it. It was sent to Burma in the mid-1950s when Prime Minister U Nu was holding a Great Buddhist Council in Rangoon to celebrate the 2,500 anniversary of Gotama Buddha’s attainment of nibbana (nirvana). As Burma is a country of very devout Buddhists (“to be Burmese is to be Buddhist”), China’s decision to send the relic twice again, in 1994 and 1996-1997 during the SLORC/SPDC era, was a powerful means of legitimizing the bilateral relationship (Seekins, 2017: 120). In November-December 2011, the tooth relic was sent a fourth time to Burma, where it was placed for veneration by devotees at the Uppattasanti Pagoda in the country’s new capital of Naypyidaw for 45 days (Ibid.; Sun Yun, 2012: 65).8

The Myitsone Dam Controversy: A Turning Point?

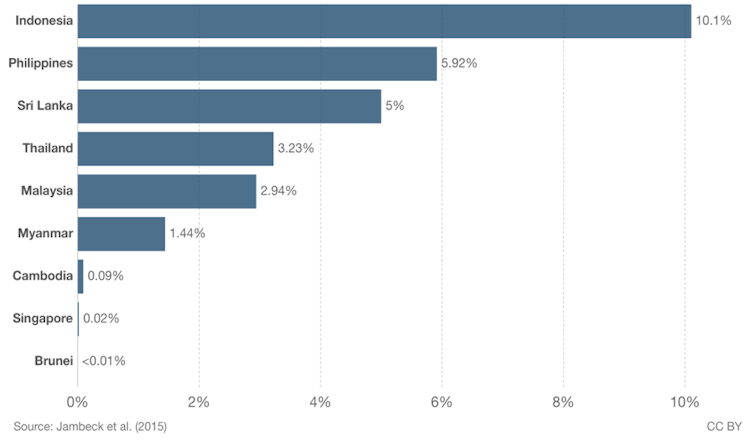

In early 2011, when the SPDC was dissolved and Thein Sein became Burma’s first president in the “hybrid” civilian-military system defined by the 2008 Constitution, China was working on three major investment projects which were designed to ensure the Middle Kingdom’s energy security and access to vital natural resources. However, each of these three projects was highly controversial. The first was the dual China-Myanmar Oil and Gas Pipelines, which, when they were completed in 2014, ran in a parallel fashion 793 kilometres from Kyaukphyu in Rakhine (Arakan) State by way of centrally-located Magway (Magwe) and Mandalay Regions to Shan State, exiting at the border towns of Muse-Ruili. A joint venture of the Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise and China National Petroleum Company, the pipelines would help alleviate a worrying bottleneck in China’s energy exports from the Middle East and the Shwe Gas Field, offshore from Rakhine State. This was the Straits of Malacca, between Malaysia and Indonesia, which since antiquity had guarded the passage to and from the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. If confrontation with the United States and its allies led to closure of the Straits to Chinese shipping by the US Navy, the project would provide cities as far east as Nanning, the capital of China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, with natural gas while the oil pipeline reaches as far as Kunming, Yunnan’s capital.

However, construction of the pipeline aroused opposition inside Burma, since it involved the forcible relocation of people, especially in Rakhine and Shan State, caused environment pollution and will provide the government with as much as US$29.0 billion in royalties for the energy re-exports over 30 years (Seekins, 2017: 148, 149).

The second project is the Letpadaung Copper Mine expansion, located in central Sagaing Region near the town of Monywa, which is a joint venture of the Myanmar Wanbao company, a subsidiary of China’s military-owned Norinco conglomerate, and Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings. In November 2012, after Thein Sein had assumed power and Aung San Suu Kyi had become a member of parliament, police attacked local people demonstrating against the mine, causing 67 injuries. Daw Suu Kyi, as head of a special government investigative committee, visited the site in March of the following year, telling the local people that they should stop their protests because Burma had to meet its contractual obligations with China. This was the first sign of a new, “pragmatic” Suu Kyi. Although it affirmed her image in Chinese eyes as a credible partner in their economic schemes, it caused great disillusionment among her supporters who had thought of her as a fearless advocate of human rights and democracy: as one local resident said: “all we had to eat was boiled rice when we supported you . . . But you are not standing with us anymore” (Ibid., 321, 322).

However, the third project, the Myitsone Dam, located in northern Kachin State, was the most controversial Chinese project as well as the biggest investment approved by the SPDC, costing US$3.6 billion (Sun Yun, 2012: 58). Like other projects, it was designed to provide China, rather than Burma, with electric power. According to Thant Myint-U:

Critics were appalled. The dam would flood an area the size of Singapore, including four villages. Nearly 12,000 people were being relocated. The location of the dam, where two Himalayan rivers joined to form the Irrawaddy, was of considerable cultural importance to the Kachin people. Activists also drew attention to the massive environmental damage that could be caused to the Irrawaddy River itself, the lifeblood of the country. No one knew exactly what was in the contract, but most believed the terms favoured the Chinese and that bribes had been paid to army generals and their crony businessmen (Thant Myint-U, 2020: 145, 146).

During the junta years, the Burmese people would have had to accept the dam project, no questions asked. But under the liberalised administration of Thein Sein, a nationwide movement emerged to halt dam construction, including a petition sent to the government, “From Those who wish the Irrawaddy to Flow Forever,” signed by almost 1,600 influential figures in the country’s public life. People throughout the country wore T-shirts inscribed: “Stop the Myitsone Dam.” Although he had mixed feelings about the dam and feared a negative reaction from China, in September 2011 Thein Sein decided that dam construction would be suspended, at least during the time he was in office (Ibid.). Almost a decade later, work had not been restarted on the dam, not only because of popular opposition and ethnic insurgency but because southwestern China now had a surplus of electrical generating power. However, it has not been formally cancelled, a move which might lead China to seek a legal remedy from the Burmese government for investment money lost (“Selling the Silk Road Spirit,” 2019).

The Chinese government and business interests were shocked, especially since Thein Sein had not consulted them before suspending the project. Relations cooled, and the pace of Chinese investment slowed. Beijing was convinced that the improvement in Burma’s relations with western countries gave the Thein Sein government courage to say “no” to China, since capital from the West and Japan would constitute viable alternatives. However, other major projects, including the oil and gas pipeline, continued, and the attacks against the Rohingyas in northern Rakhine State carried out in 2017 by the Tatmadaw and local vigilantes, leading to over 700,000 of them fleeing to Bangladesh, aroused a firestorm of western criticism. This was focused especially on Daw Suu Kyi, and led to targeted sanctions on some individuals, including commander-in-chief Min Aung Hlaing, who personally directed the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingyas (Ibid.). Predictably, Beijing offered support to the government now led by Daw Suu Kyi as “State Counsellor,” and the turbulence in Burma-China relations transitioned into a new era of co-operation.

Once she entered into the political system with her election to a parliamentary seat in 2012, Daw Suu Kyi proved to be almost flawlessly friendly to China’s interests. Her decision on the Letpadaung Copper Mine issue was a solid indication of this. After her National League for Democracy government was elected in a landslide in November 2015, promising (falsely, it turned out) quick advancement to a fuller democratic politics and society, she and the Chinese leadership became something like a mutual admiration society. China’s foreign minister Wang Yi went to Naypyidaw to congratulate her on her 2015 election victory the following year, the first foreign dignitary to do so, and Daw Suu Kyi herself went to Beijing to confer with Chinese president Xi Jinping. Their meeting was warm, amply laced with language about Chinese and Burmese being pauk phaw, or “distant cousins.” Again, when Daw Suu Kyi was being bitterly criticised by western countries over the Rohingya issue, she was given moral support by Xi and other top Chinese officials during a December 2017 visit to Beijing. The Chinese also assisted greatly in her ultimately fruitless efforts to achieve reconciliation with the ethnic armed organisations (Thant Myint-U, 2020: 228, 247).

In one of her “Letters from Burma” published in the Japanese newspaper Mainichi Shimbun in April 1996, Daw Suu Kyi commented:

To observe businessmen coming to Burma with the intention of enriching themselves is somewhat like watching passers-by in an orchard roughly stripping off blossoms for their fragile beauty, blind to the ugliness of despoiled branches, oblivious of the fact that by their action they are imperiling future fruitfulness and committing an injustice against the rightful owners of the trees. Among these despoilers are big Japanese companies. (Aung San Suu Kyi, 1996: 3).

Daw Suu Kyi, who had spent a year as a researcher at Japan’s Kyoto University, was doubtlessly thinking of the Japanese springtime custom of viewing cherry blossoms when she wrote this. In relation to China, however, by 2019 Burma’s democracy icon was walking firmly on pragmatism’s low road.

Burma and the One Belt, One Road Initiative

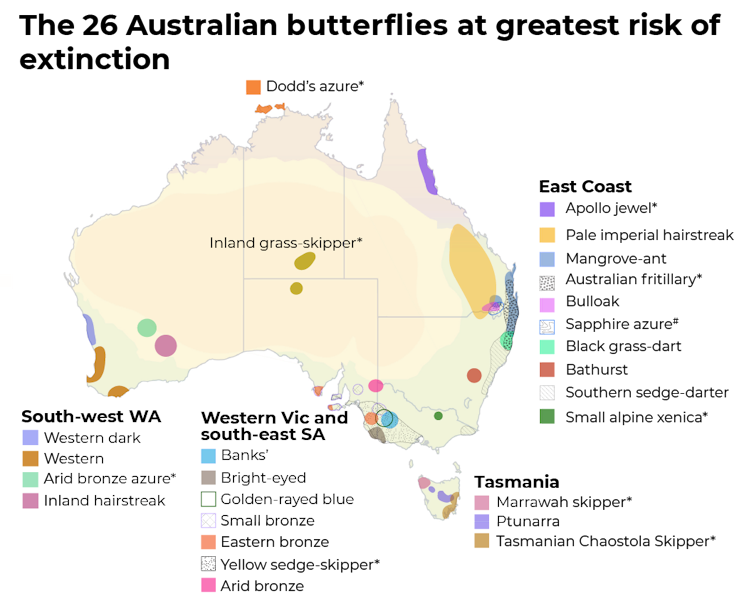

China’s President Xi Jinping announced his One Belt/One Road Initiative, BRI (Chinese: 一帯一路 ) in 2013, an ambitious blueprint to use Chinese and international capital to construct economic linkages (or “corridors”) extending from China by land and sea to the western part of the Eurasian landmass. Major BRI projects include: the China-Indochina Corridor, the China-Bangladesh-India Corridor, the China-Pakistan Corridor, the China-Central Asia-West Asia Corridor, the China-Mongolia-Russia Corridor, the New Eurasia Landbridge, and the China-Myanmar Corridor (also known as the China Myanmar Economic Corridor, or CMEC). While its goal is construction of transportation and communications infrastructure throughout Eurasia and beyond, stimulating the rapid growth of local industries and promoting growth, the scope of its ambition is perhaps best understood as covering an area larger than the 13th century Mongol Empire, which did not include South Asia or most of Southeast Asia. Many of the countries with the most ambitious projects included within the BRI are members of Beijing’s new Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, set up as an alternative to the western and Japanese dominated World Bank (“Selling the Silk Road Spirit,” 2019).

Essential to this vision is China’s hope to gain easy and stable access to the Indian Ocean through Burma and Pakistan (although tensions between China and India and Vietnam may prevent implementation of corridors in the Subcontinent and Indochina). According to the Transnational Institute (TNI): “(t)he sheer size of the initiative – 136 countries have received US$90 billion in Chinese foreign direct investment and exchanged US$6.0 trillion in trade with China – can make the BRI appear monolithic and inevitable” (Ibid.). In fact, it is more of a vision than a plan, and while it is legitimized by the central government in Beijing, it contains a large number of initiatives promoted by Chinese state-owned companies, provincial governments and private enterprise. In other words, in the TNI’s words: the BRI is “a broad framework of activities, rather than a predetermined plan” (Ibid.). While politicians in Washington D.C. view the BRI as Beijing’s sinister plot to take over the world, or seduce developing countries into “debt traps,” the scheme is not centrally directed and, like other foreign investment schemes, extremely vulnerable to unstable conditions on the ground.9

Countries which signed cooperation documents related to the Belt and Road Initiative (CC BY-SA 4.0)

For a relatively poor country such as Burma, however, the BRI is a huge deal. The China Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) was initiated in 2017 by Foreign Minister Wang Yi, following the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) by the two governments. Given that the major obstacle to Chinese investment in the country has been the continued civil war between the central government and ethnic armed organisations, the launching of the CMEC was accompanied by a renewed effort to carry out “peace” negotiations by Aung San Suu Kyi’s government. While successful projects such as the Oil and Gas Pipeline already contributed to solidifying economic and infrastructure ties between the two countries, four projects were designated as priorities for furthering the BRI vision:

- The North-South Energy Transmission Project, the integration of the electrical grids of China and Burma, which would impact ethnic minority regions such as Shan and Kachin States and could leave Burma dependent on China for electricity;

- A China-Burma High Speed Railway, connecting Yunnan Province with Burma, its Indian Ocean terminus being the Rakhine State port of Kyaukphyu;

- A “Sino-Myanmar Land and Water Transportation Bridge which would link Yunnan with the Indian Ocean in large measure through exploitation of the Irrawaddy River; and,

- Special Economic Zones (SEZ) and Industrial Zones, including the Kyaukphyu SEZ in Rakhine State (“Selling the Silk Road Spirit, 2019”).

Another important Chinese project is the “New Yangon City Project,” a ninety square kilometer new city to be constructed to the west of Rangoon (Oo, 2021). Although plans to construct an ultramodern “new city” near the old commercial capital were proposed soon after the 1988 SLORC takeover, none of these reached fruition, although the building of Naypyidaw as the new national capital could be considered an alternate scheme to insulate Burma’s elites and power-centre from popular unrest (Seekins, 2019: 81-106).

A Kachin political activist, Lahpai Seng Raw, has described the BRI from the perspective of vulnerable ethnic minorities:

There is no doubt that a storm is brewing. CMEC is looming over us like a black, threatening mass of cloud, further aggravating the raging political storm of unresolved political grievances and environmental degradation that envelop us. This is the harsh reality that we Kachins face with the advent of CMEC. And, like it or not, we must face it and its resultant effects. As things stand now, it would seem that we are caught between the devil and the deep sea, with not many good options in sight. The question facing us now is whether it would be more pragmatic to cast our lot with China and its Belt Road Initiative rather than the transformation process under Myanmar rule, and the non-negotiable, centralized “Peace Process”?

. . . As it is, we do not have a choice of opting for the Devil or the Deep Blue Sea, but will have to face both of them head on (Lahpai Seng Raw, 2019).

Conclusions: the 2021 Coup d’Etat and Beijing’s Geopolitical Nightmare

Many people who looked at Burma’s internal politics from an overly rational viewpoint were shocked by the February 1 coup d’état (“the generals already have it pretty good”). Perhaps they should have paid more attention to a basic legitimizing principle in the Tatmadaw’s political worldview, the difference between “national politics” and “party politics”: Under party politics, civilian politicians pursue diverse particular interests, while national politics is the supreme responsibility of the Tatmadaw as the protector and enforcer of national unity and identity, values which are viewed as constantly under assault from foreign countries (Seekins, 2017: 384, 385). This doctrine was formulated in the early 1990s by pro-SLORC spokesmen, but continues to be taken very seriously by the army’s top brass in the third decade of the twenty-first century. So seriously, in fact, that under their command the army and police have killed hundreds of peaceful and mostly unarmed protesters nationwide, with the violence continuing to escalate through March and April.

In a March 2021 interview with the National Committee on US-China Relations in Washington, broadcast on YouTube, analyst Sun Yun claimed that following the coup d’état, China sought to be “neutral,” observing the principle of non-interference in the domestic affairs of another country which is one of the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, proclaimed both by China and Burma. She said that the principle “ties China’s hands,” although Beijing’s leaders really do not approve of the military takeover. She also says that China values Burma more for its strategic location than its natural resources, given the BRI’s ambition to establish a land link between the interior of China and the Indian Ocean (Sun Yun, 2021).

In fact, as the history related above shows, the People’s Republic of China has tended to observe this principle of non-interference in the breach when it had sufficiently compelling interests to do so: for example, it gave sanctuary to Burmese communist exiles during the 1950s and 1960s, armed and sent the People’s Army over the border in January 1968 and choose to support the SLORC/SPDC junta in 1988-2011 both militarily and economically, while largely keeping its distance from Aung San Suu Kyi and the pro-democratic opposition until after 2011. At the same time, China gave aid to the United Wa State Army in eastern Shan State, allowing it to establish an autonomous mini-state with a first-class armed force, sold weapons to several other ethnic armed organisations (such as the Arakan Army) and has exploited Burma’s natural resources, like jade, forests and natural gas, with little concern for the impacts, such as land grabbing, abuse of ethnic minorities and severe environmental pollution.

Seeing Burma’s political stability as its top priority in bilateral relations, Beijing found a reliable partner in carrying out its BRI agenda in Aung San Suu Kyi. Indeed, two weeks before the coup Foreign Minister Wang Yi met with her in Naypyidaw to sign agreements related to the China Myanmar Economic Corridor. According to a Thai diplomat, the closeness of Daw Suu Kyi to Beijing seems to have, in the words of one correspondent, “hit a nerve with the military’s high command” He went on to say that “the military felt threatened by this” (Macan-Markar, 2021).

The possibility that Burma will slip into civil war is highly likely. On April 13, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, warned that the country could become another Syria, a battleground in which society collapses and refugees flee to other countries in huge numbers (“Myanmar heading toward ‘full blown conflict,’” 2021). With the fatalities increasing at the hands of the Tatmadaw and police and the determination of ordinary Burmese people to regain at any cost the admittedly imperfect democracy that was stolen from them, there is little likelihood of compromise on either side. Although China, which first described the coup as a “cabinet reshuffle,” wants the crisis to simply go away, it won’t (Lintner, 2021). It will get worse.

Already, Burmese people have expressed anti-Chinese sentiments, seeing Beijing as the enabler of the military regime and its violence. Thousands of people in the streets of Rangoon, Mandalay and other cities have held up signs condemning China for condoning the coup and gathering at the Chinese embassy to protest (“China get out of Myanmar” say pro-democracy supporters,” 2021). On March 14, fires were started in Chinese-owned factories in Hlaing Thayar, a township of Rangoon. Although there is suspicion that the fires might have been started by pro-regime agents provocateurs rather than protesters, Beijing predictably urged the regime to better protect its projects (Oo, 2021; “China again seeks Myanmar regime’s assurances on oil, gas pipeline security,” 2021).

With the anti-Chinese riots of June 1967 as a precedent, it would be tragic if Chinese residents of Burma, many of whose families have lived in the country since the colonial era, were targeted for attack. Several Burmese-Chinese people have been killed during the street protests, including a 19 year-old woman, Kyal Shin (nicknamed “Angel”), who was shot dead in Mandalay on March 3rd. In Rangoon, the Chinese community has stated publicly its support for the protests and denials that its members are loyal to the People’s Republic (Lintner, 2021).

The future for Burma looks exceedingly grim, both because foreign countries including China seem unable or unwilling to intervene positively to help settle the crisis, and because as the Tatmadaw escalates its violence, the ordinary people increase their resistance. Should the violence continue, anti-regime citizens, possibly in alliance with ethnic armed organisations, are likely to turn to terrorist measures as a means of crippling the regime and its Chinese backers. Led by Aung San Suu Kyi, protests against the SLORC/SPDC during 1988-2010 were largely non-violent, but this could change, and the urge to “make China bleed” by targeting its citizens and projects, like the hugely vulnerable oil and gas pipelines, could be irresistible.

In such an eventuality, should China choose to downgrade its economic engagement or pull out of Burma entirely, it might turn to the China-Pakistan Corridor as a feasible alternative for gaining access to the Indian Ocean (“Selling the Silk Road Spirit,” 2019). Sun Yun has commented that as of 2019, the BRI connection with Pakistan had made considerable progress compared to the CMEC: President Xi has already visited the country and project commitments of more than US$46.0 billion have already been signed (Ibid.).

In looking back on their two millennia of resistance against an expanding China, Vietnamese historians have often said that China has played a dual, ambiguous role in their country’s development: “both our oppressor, and our teacher.” In Burma, which engaged fully with China much more recently, it seems that despite deep suspicions of China held by some of the Tatmadaw’s top leaders, the Burmese army has been used by Burma’s northern neighbour to “pacify” the country in a vain search for stability. Given this situation, the famous comment of the Roman historian Tacitus on the Roman occupation of Britain seems appropriate: “they have made a desert, and call it peace.”

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @crg_globalresearch. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Donald M. Seekins is Emeritus Professor of Southeast Asian Studies in the College of International Studies of Meio University in Okinawa, Japan.

Sources

Aung San Suu Kyi. 1996. “Letter from Burma.” Mainichi Daily News, April 22, p. 3.

Bi Shihong. N.d. “The Economic Relations of Myanmar-China.” Chiba, Japan: Institute for Developing Economies.

“China again seeks Myanmar regime’s Assurances on Oil, Gas Pipelines.” 2021. The Irrawaddy, April 2 at www.irrawaddy.com accessed on 04.10.2021.

“’China Get Out of Myanmar’ Say Pro-Democracy Supporters.” 2021. The Irrawaddy, April 2 at www.irrawaddy.com accessed 04.10.2021.

“Debunking the Myth of Debt-Trap Diplomacy.” 2020. Research Paper, August 19. London: Chatham House at www.chathamhouse.org accessed on 04.06.2021.

Lahpai Seng Raw. 2019. “China’s Belt & Road Initiative: a Cautionary Tale for the Kachins.” January 10. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute.

Lintner, Bertil. 2021. “China’s Myanmar Dilemma grows deep and wide.” Asia Times, March 25, at www.asiatimes.com accessed on 04.11.2021.

Lintner, Bertil. 1999. Burma in Revolt: Opium and Insurgency since 1948. Chiang Mai: Silkworm.

Lintner, Bertil. 1993. “Rocks and a Hard Place.” Far Eastern Economic Review, September 9, p. 26.

Macan-Markar, Marwaan. 2021. “China treads lightly on Myanmar coup with billions at stake.” Nikkei Asia, March 5 accessed on 03-11-2021.

Mizuno Atsuko. 2016. “Economic Relations between Myanmar and China.” Pp. 195-224 in Konosuke Okada, ed. The Myanmar Economy: Past, Present and Prospects. Tokyo: Springer Japan.

Mya Maung. 1992. Totalitarianism in Burma: Prospects for Economic Development. New York: Paragon House.

“Myanmar heading towards a ‘full-blown conflict, UN rights chief warns.” 2021. UN News, April 13, at www.news.un.org accessed 04.14.2021.

Oo, Dominic. 2021. “China’s Interests going up in Flames in Myanmar.” Asia Times, March 16, at www.asiatimes.com accessed on 04.12.2021.

Seekins, Donald M. 2019. “’Centering the City’: the Upattasanti Pagoda as Symbolic Space in Myanmar’s new capital of Naypyidaw.” Pp. 81-106 in Henco Bekkering, et al. eds. Ideas of the City in Asian Settings. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Seekins, Donald M. 2017. Historical Dictionary of Burma (Myanmar). 2nd edition. Lanham MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Seekins, Donald M. 2011. State and Society in Modern Rangoon. London: Routledge.

Seekins, Donald M. 2007. Burma and Japan since 1940: from ‘Co-Prosperity’ to ‘Quiet Dialogue.’ Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Press.

Seekins, Donald M. “Burma-China Relations: playing with Fire.” Asian Survey, vol. 37:6, June, pp. 525-539.

“Selling the Silk Road Spirit: China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Myanmar.” 2019. Myanmar Policy Briefing, No. 22, November. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute.

Sun Yun. 2021. “The Myanmar Coup, China and the US.” Interview with the National Committee on US-China Relations on YouTube, March 8, accessed 03.09.2021.

Sun Yun. 2012. “China in the Changing Myanmar.” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, vol. 31:4, pp. 51-77.

Thant Myint-U. 2020. The Hidden History of Burma: Race, Capitalism and the Crisis of Democracy in the 21stCentury. New York: W.W. Norton.

Thaw Kaung, U. 2004. “Preliminary Survey of Penang-Myanmar Relations from the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries.” Pp. 163-186 in Selected Writings of U Thaw Kaung. Rangoon: Myanmar Historical Commission.

Notes

1 Some Chinese observers see a historical precedent to the One Road/One Belt Initiative in the Silk Road which connected the Han and Tang Empires of China with countries in the West and, more significantly, the voyages led by Admiral Zheng Ho to the South China Sea and Indian Ocean during the early Ming Dynasty, although outside of island Southeast Asia, the impact of these expeditions was short-lived

2 To this day, Burmese refer to the Chinese as Taiyoke, a term that is derived from the Chinese word for “Turk.” This may have referred to Muslim Turkish or Central Asian soldiers in Kublai Khan’s army (Seekins, 2017: 147).

3 It was Siam (now known as Thailand) which benefited the most from the Qing campaigns. Hsinbyushin ordered Burmese troops to retreat from Siam to fight the Manchus, and a new Siamese royal dynasty, the Chakri, was established in 1782 with its capital at Bangkok. Thereafter, Siam successfully countered Burmese incursions under Hsinbyushin’s successor, Bodawpaya (r. 1782-1819).

4 Supplies were offloaded at Rangoon and carried by rail to Lashio, a town in the Shan States. From there, they were taken by truck over the Burma-China border to Kunming, capital of Yunnan.

5 Being a permanent member of the UN Security Council, China has veto power over its deliberations. Both China and Russia vetoed any attempt of the UNSC to take a strong stand on the February 1, 2021 coup d’état.

6 No one is quite sure how many Chinese entered and sojourned in Burma during the SLORC/SPDC period. Census figures are unhelpful on this issue, and one English language publication based in Hong Kong, Asiaweek, suggested that hundreds of thousands of Han Chinese may have entered Burma after flooding in southern China. Mandalay itself is estimated to be 30 percent Chinese. The inflow has reportedly deeply changed the demographic profile of Upper Burma (Seekins, 2017: 150, 151).

7 While in Rangoon in 2005, I visited a couple of these developments. At one, I asked a Burmese saleswoman who bought these luxury mansions. She replied: “Oh, I don’t really know, but they’re Chinese.”

8 Replicas were made of the original tooth relic, and placed in “Tooth Relic Pagodas” in Rangoon and Mandalay as well as the Uppattasanti Pagoda in Naypyidaw (Ibid.).

9 “Debt traps” refers to the alleged tactic of China’s luring poor countries into assuming heavy loan burdens and then, when they cannot service them, seizing the assets. Thus, China can extend its power and influence far beyond its borders. See “Debunking the myth of ‘Debt-trap Diplomacy’ (2020).

Featured image: China’s ‘Burma Road’ project, part of the broader Belt-and-Road infrastructural initiative. (Source: APJJF)